Scientists conducted the first known ocean meteorite recovery off the coast of Grays Harbor County earlier this week, and are confident they found several rocks that are from the March 7 meteorite fall that lit up the night sky.

Marc Fries, NASA’s curator of cosmic dust, said this was the largest U.S. meteorite fall he has seen since weather radar began recording them in the mid-1990s.

“This one was enormous, it looks like about two (metric) tons of meteorites fell,” said Fries, who gave a presentation to about 20 people at Grays Harbor College on Thursday.

On the night of March 7, the sky over Grays Harbor flashed bright white, and was accompanied by the loud rumbling sound of a sonic boom as the rocks entered earth’s atmosphere.

It was such a large meteorite fall, Fries said, that it was the first time he’d seen an ocean seismometer on the sea floor detect a sonic boom.

There have been about 12 meteorite falls that Fries hasn’t been able to recover samples from in the past 10 years, and most occurred in the ocean where it’s more difficult to do so.

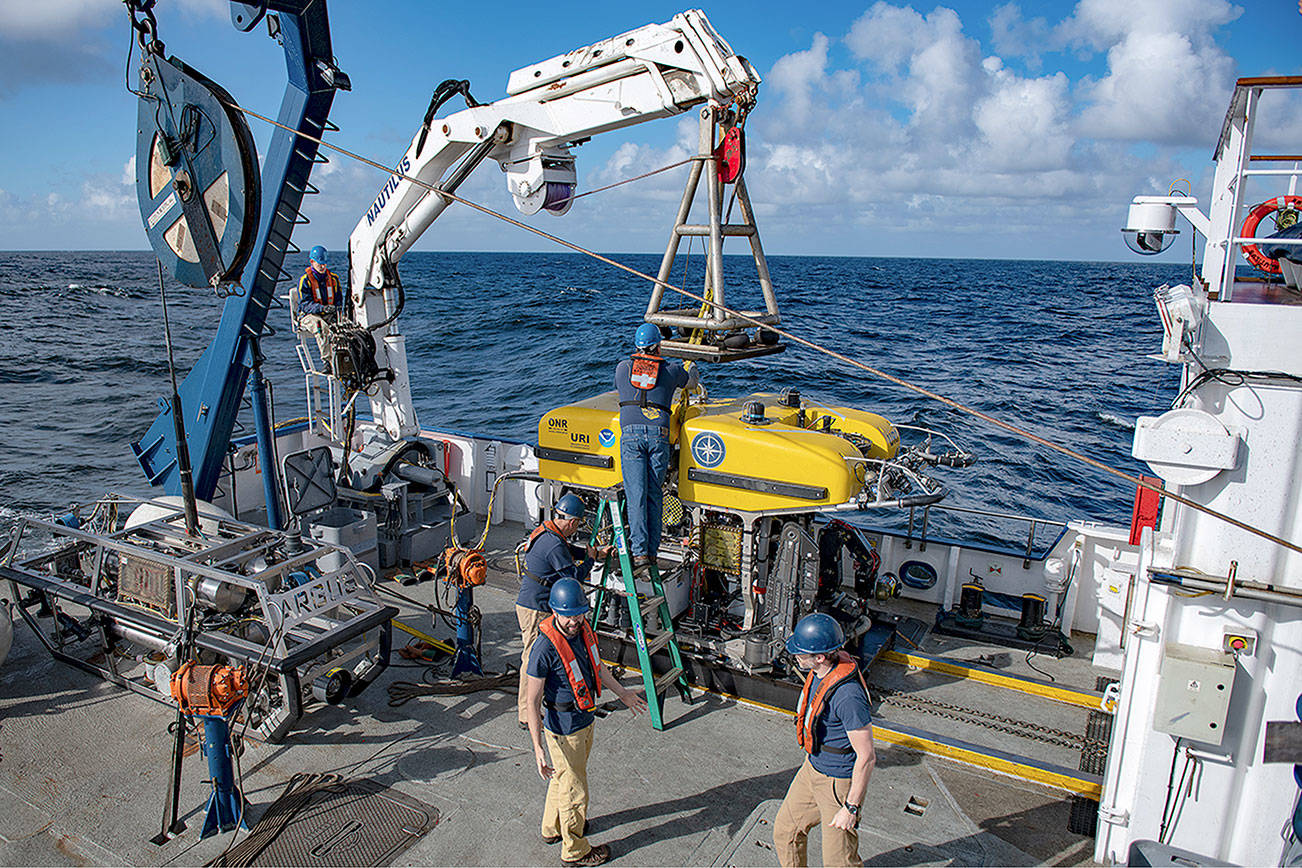

But due to its large size — the largest detected chunk was about 4.5 kilograms — Fries and a team of scientists and staff from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) on the Nautilus exploration ship decided to try and recover the pieces.

Last Monday, the group traveled to the spot where they suspect the meteorites fell, about 20 kilometers off the coast from Queets in the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary.

They used remote-control vehicles to traverse the ocean floor. Those machines used suction tubes and magnets to recover seven sediment samples from the 100-meter-deep area of ocean.

Already, Fries said he has identified four small fragments that he’s optimistic are either the meteorite’s glassy melted crust, or some of the inner minerals that he described as having a greenish color. These fragments range from two and a half to four millimeters in diameter, he said, and could allow scientists to determine what type of meteorite it is and where it came from.

These samples will be taken to either Johnson Space Center in Houston or the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., where they will be further identified and then kept in a collection.

From weather data that picked up the falling meteorites, Fries believes that the meteorites only fell within a six-by-six kilometer area in the ocean, but one man from Moclips is skeptical.

Franklin Delacruz, 42, found what he thinks is a meteorite in the sand about 10 miles north of Taholah. It’s about two inches in diameter and is fully magnetic as most meteorites are.

On March 25, Delacruz said he and a friend were looking for ancient village artifacts in the area he found the rock. According to him, the rock’s tip was sticking out of the sand in a 7-foot-long trench that was about 2 feet deep and got wider as it approached the end the rock was in.

He’s not sure, but Delacruz thinks this rock could be from the March 7 meteorite fall. Around the depression where he found the rock, Delacruz said there was splattered sand and tall swamp grass that was lying down in the direction of the rock.

When asked if he thinks it could be from an older meteorite fall, Delacruz said the splattered hole and sand were too fresh to be very old.

“I’m an avid hunter, and when we track animals, we can tell what day they’ve been in there just because of how their hooves leave prints in the sand,” Delacruz said while running his fireworks stand in Taholah on Monday. “We could see an imprint, and tell how many days, and possibly hours it had been.”

When Fries looked at an email photo of the rock, he said it’s unlikely Delacruz’s rock could be from the March 7 event because of how jagged and rusty it looked.

“It didn’t look neatly rounded,” said Fries. “Normally when a meteorite falls, it’s basically just been abraded badly. The surface is melted off, everything’s rounded and there’s no pointy corners on it. That one looked like it had fractured.”

Fries said it’s possible this rock could be from an earlier meteorite fall, as there have been six recorded in Washington. But he said because of how steep an angle the meteorites fell in and according to radar data “the vast bulk of the fall is in that site (in the ocean).”

He suggested that Delacruz take his rock to the Cascadia Meteorite Laboratory located at Portland State University to have them determine if it’s a meteorite and when it fell.

Delacruz said he plans to sell the rock if it is a meteorite.

“If there’s great value, I’ll find someone who wants to buy it. I have family.”

The crew members were unable to recover any potential meteorites bigger than a few millimeters, as Fries said the ocean floor was so soft that most of the larger pieces sank too deep for them to find.

“What we found is it’s like angel food cake,” said Fries. “Anything that landed sank into it. We didn’t find any rocks — everything sank into the mud. They’re down there, but we couldn’t see them with our gear.”

Fries said it will take a few weeks of analysis before we knows what kind of meteorite it is.

If tests determine that this meteorite was particularly rare, or that a massive amount remains hidden beneath the ocean floor, Fries said he would “love” to take another crew back to search with better digging equipment in the future.