By Julia Rosen

Los Angeles Times

Flames are spreading across the Amazon rainforest this summer, spewing millions of tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each day. But scientists say that’s not their biggest concern. They’re far more worried about what the fires represent: a dramatic increase in illegal deforestation that could deprive the world of a critical buffer against climate change.

More than a soccer field’s worth of Amazon forest is falling every minute, according to Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research, known as INPE. Preliminary estimates from satellite data revealed that deforestation in June rose almost 90% compared with the same month last year, and by 280% in July.

The Amazon is a key component of Earth’s climate system. It holds about a quarter as much carbon as the entire atmosphere and single-handedly absorbs about 5% of all the CO2 we emit each year.

But if such rapid deforestation continues, it will foil efforts to keep global temperatures in check. Scientists fear parts of the Amazon could pass a critical threshold and transform from a lush rainforest into a dry, woody grassland. And that could bring catastrophic consequences not only for people in South America, but also for everyone around the world.

“We might be very, very close to the tipping point,” said Carlos Nobre, a climate scientist at the University of Sao Paulo in Brazil. And if we cross it, he said, “it’s irreversible.”

The trend is particularly alarming because it comes after more than a decade of progress toward preserving the world’s largest rainforest. Many blame the anti-environmental rhetoric of Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s new far-right president, and fear that it will put global climate efforts in jeopardy.

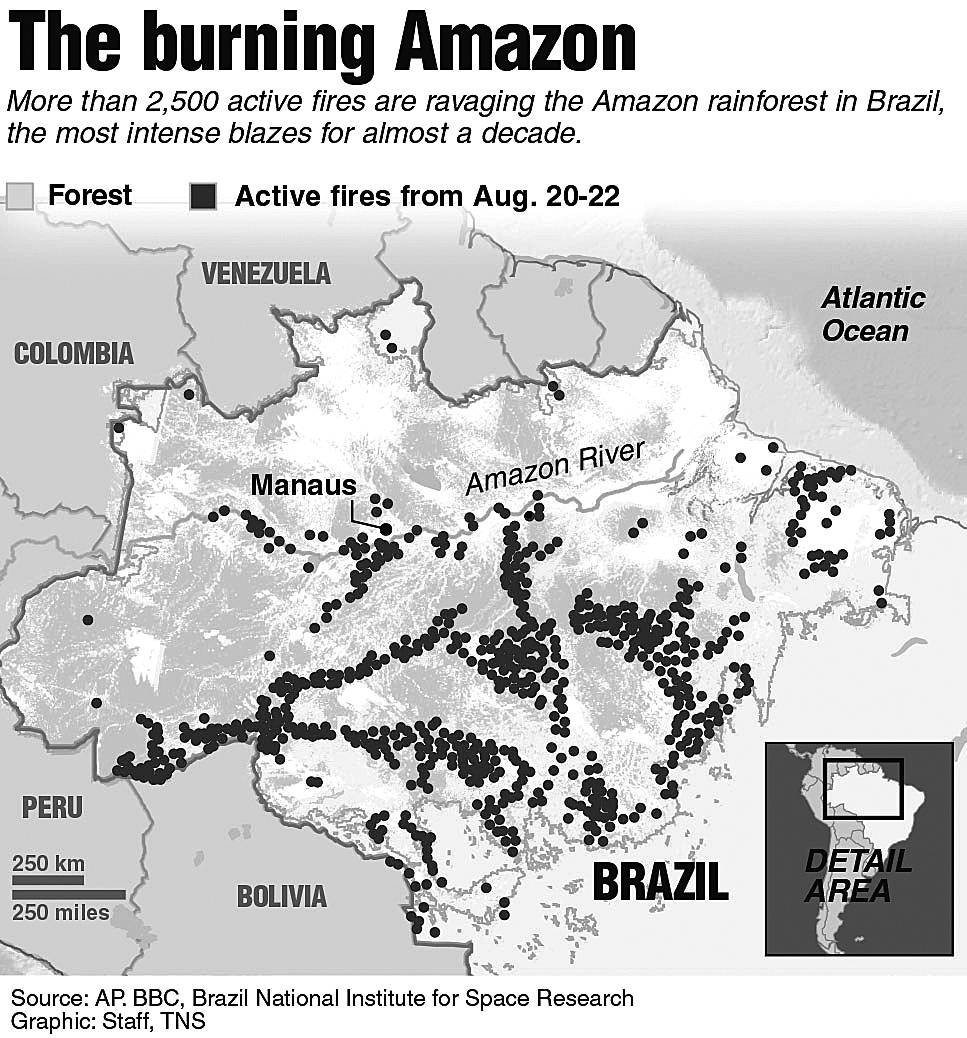

Left to nature, the Amazon rarely burns. But INPE has counted more than 25,000 blazes in the Amazon in August alone. The smoke grew so thick it cast the city of Sao Paulo, which lies more than 1,000 miles away, into daytime darkness.

The fires have sparked an international outcry. But they came as no surprise to those who keep a close watch on the Amazon. Satellite images in May, June and July showed an uptick in deforestation. It was only a matter of time before the flames followed, said Doug Morton, chief of the Biospheric Sciences Laboratory at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

“This is the expected one-two punch,” he said.

Instead of axes and machetes, people now use bulldozers and giant tractors with chains to pull down the Amazon’s towering trees. A few months later, they torch the trunks. It’s the only realistic way to remove such huge amounts of biomass, Morton said. “It’s slash and burn, 21st century.”

Thousands of acres at a time are being cleared for large-scale agriculture, he added. The land is primarily used as pasture for cattle —one of Brazil’s major exports —or for crops such as soybeans.

This marks a troubling reversal in the fight to end deforestation, long a linchpin of global climate policy.

In 2004, the Brazilian government began cracking down on forest destruction by designating more protected areas and reserves for indigenous people. Violators were fined or arrested and forest loss declined 75% by 2012.

What’s more, the country’s agricultural production continued to increase, demonstrating that development and conservation could go hand in hand, said Nobre, who has been studying the Amazon for more than 35 years.

“It was a big success,” he said. “Everybody was happy.”

However, deforestation rates have increased sharply since May, a few months after Bolsonaro took office. So far, more than 2,000 square miles of forest have fallen this year.

Bolsonaro has railed against protections for indigenous land and promised to boost the country’s economy. He has also weakened the government’s capacity for oversight and indicated he would not go after farmers, loggers and miners who seize and clear forest.

Some say his words have been enough to trigger a burst of deforestation. (Government representatives did not respond to requests for comment.)

“This actually gives a signal to people on the ground that they can do whatever they want and they won’t be punished,” said Ane Alencar, director of science at the nonprofit Amazon Environmental Research Institute.

President Donald Trump’s trade war may also play a role by making Brazil a leading supplier of China’s soybeans. “This is, to some extent, driven by global demand for commodities, because that’s what potentially gives the land value to farmers and ranchers,” said ecologist Oliver Phillips of the University of Leeds in the U.K.

Bolsonaro has called INPE’s deforestation figures a “lie” and recently fired the agency’s director. He has also claimed, without evidence, that environmental groups started the fires to embarrass his administration.

But scientists said there’s no question that the blazes are linked to deforestation. The burns are clustered near roads along the so-called arc of deforestation, and they line up with the areas of greatest land clearing earlier in the year, Morton said. The power of the fires also betrays their origins.

“Big towering columns of smoke need a big fire beneath them,” he said. This is not farmers burning fields or clearing overgrown pastures. “This is burning enormous piles of wood.”

As bad as they are, this year’s fires are not off the charts. Between January and August, scientists have counted more than 40,000 blazes in the Amazon region; in 2010, during a severe drought, they spotted 60,000 blazes over the same period of time.

The weather this year is pretty normal, so that’s not what’s driving the fires, said Luiz Aragao, a scientist at INPE. Instead, the pattern resembles the years of the early 2000s, when deforestation peaked. Back then, scientists tallied nearly 80,000 fires between January and August, and the burns closely tracked the area of cleared forest.

“This is eerily familiar,” Morton said.

And it’s not over yet. It’s common to let felled trees dry before burning them, so the spike of deforestation that INPE recorded in July will bring more fires in September, Alencar said: “We still have two months to go.”

The fires —and the deforestation behind them —are an immediate concern for global warming. Already, Brazil’s blazes have released 200 million tons of CO2 into the atmosphere —about three times as much as all of the wildfires in California last year, according to Europe’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service.

Aragao estimates that by the end of the year, greenhouse gas emissions will be similar to those in 2009, when clearing and burning the Brazilian Amazon released about 500 million tons of CO2. That’s equivalent to roughly 1% of the world’s total emissions in a year. (If the fires spread from piles of toppled trees into intact forests, emissions could be higher, he said.)

Much more worrying than the fires themselves is the perilous state of the Amazon, scientists said.

Climate models suggest that the combined effects of deforestation and global warming could push the Amazon past a critical tipping point and turn two-thirds of the rainforest into a kind of degraded savanna, Nobre said.

That’s because the Amazon creates its own weather. And if it loses that power, everything could change.

The moisture that sustains the Amazon evaporates off the Atlantic Ocean and falls as rain when it reaches land. Normally, that would be the end of the story.

But in the Amazon, billions of trees conspire to put some of that water back into the air, making rain for the rest of the forest and the agricultural areas downwind. Every leaf releases small amounts of water when it opens its pores to take in CO2, a key ingredient for photosynthesis.

Take away enough trees, however, and that cycle will collapse.

Rising CO2 levels will also choke off Amazonian rainfall, said Abigail Swann, a climate scientist at the University of Washington. With more of the gas in the air, trees don’t need to open their pores as often to bring in the same amount of carbon. This alone accounts for about half of the decline in rainfall projected by models, according to a 2018 study by Swann and others.

Global warming adds to the problem by making the climate hotter and drier, stressing trees and increasing the risk of uncontrolled wildfires that could threaten large areas of forest.

The ultimate fate of the Amazon is still up for debate. “This is a huge question lots of people are trying to answer,” Swann said.

If scientists’ worst fears come to pass, it could become all but impossible to meet global climate goals aimed at limiting the worst effects of global warming.

The Amazon plays a key role in offsetting our emissions and sequestering carbon. But already, climate change has suppressed the forest’s ability to suck up CO2 by one-third, and in the worst years, fires release about as much carbon as the forest traps. Now, Nobre and others fear that if large swaths of the forest transform, about 50 billion tons of stored carbon —roughly 10 times the world’s annual emissions —could escape.

Damage to the Amazon could reduce its powerful cooling effects too. When water evaporates from tree leaves, it removes heat from the atmosphere. As a result, tropical forests act like giant air conditioners, both locally and globally. According to one analysis, protected forests in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso were 3 degrees Celsius (5.4 degrees Fahrenheit) lower than surrounding pastures and farms.

There’s also the potential for changes in the Amazon rainfall to disrupt weather patterns around the world. One study found that deforestation of the Amazon would affect precipitation in North America, including in California and the Midwest.

Residents of South America would suffer some of the most dire effects of a transformed forest. Millions of indigenous people live in the Amazon and depend on the forest for survival. (So do 10% of the world’s plant and animal species.)

Agricultural areas to the southeast would be hit hard too; they rely on the Amazon for most of their rain, Swann said.

Scientists already see worrisome changes. In the southeastern Amazon, the dry season lasts three weeks longer than it did 40 years ago, Nobre said.

His research suggests that a tipping point could occur when deforestation hits 20% to 25%. The Amazon has lost between 15% and 17% of its trees, and at current deforestation rates, the rainforest could cross Nobre’s threshold in 15 to 30 years.

“We are almost seeing the tipping point before us,” he said.

Most Brazilians want to see the forest protected. A recent survey by the Brazilian Institute of Public Opinion and Statistics and the activist group Avaaz found that 96% of respondents would like the government to combat illegal deforestation. The percentage was the same among Bolsonaro’s supporters.

But while domestic policies are important, Nobre said a big part of the solution lies elsewhere. For instance, countries that import goods from Brazil should refuse to buy products that contribute to forest loss, he said. (Finland is urging the European Union to consider a ban on Brazilian beef.)

Nobre also argues that the world must help the region develop a new kind of economy that “keeps the forest standing.”

“It’s not a fight of Amazonian countries,” he said. “This is a global fight.”