By Amina Khan

Los Angeles Times

North America has lost nearly 3 billion birds since 1970, according to a new analysis of bird survey and radar data.

The sharp decline, described in a study in the journal Science, is not just bad for birds. It also bodes ill for the ecosystems those birds inhabit, and points to a need for action to halt and perhaps reverse the drop, scientists said.

“Three billion was a pretty astounding number for us,” said lead author Kenneth Rosenberg, a conservation scientist at Cornell University and American Bird Conservancy.

Many animals are threatened with extinction because of human activity, but that’s not the only problem they face. Loss of abundance spells trouble too because it can have profound consequences for the ecosystems they inhabit.

Conservationists studying North American birds had known that some at least some species were declining, but they didn’t know what the net loss, or gain, might be.

“Previously we didn’t have good estimates of population size,” Rosenberg said. “We knew the trends, but we didn’t really know how many birds of each kind were out there.”

To find out, he and his colleagues analyzed more than a dozen bird survey data sets that covered 529 bird species across a host of ecosystems in the U.S. and Canada. These data sets, such as the North American Breeding Bird Survey, rely on citizen scientists to conduct counts along roadsides across North America every year, and boast records going back decades.

The researchers were also able to track feathered fliers with a network of 143 weather radars, which often catch migrating birds on their nighttime routes.

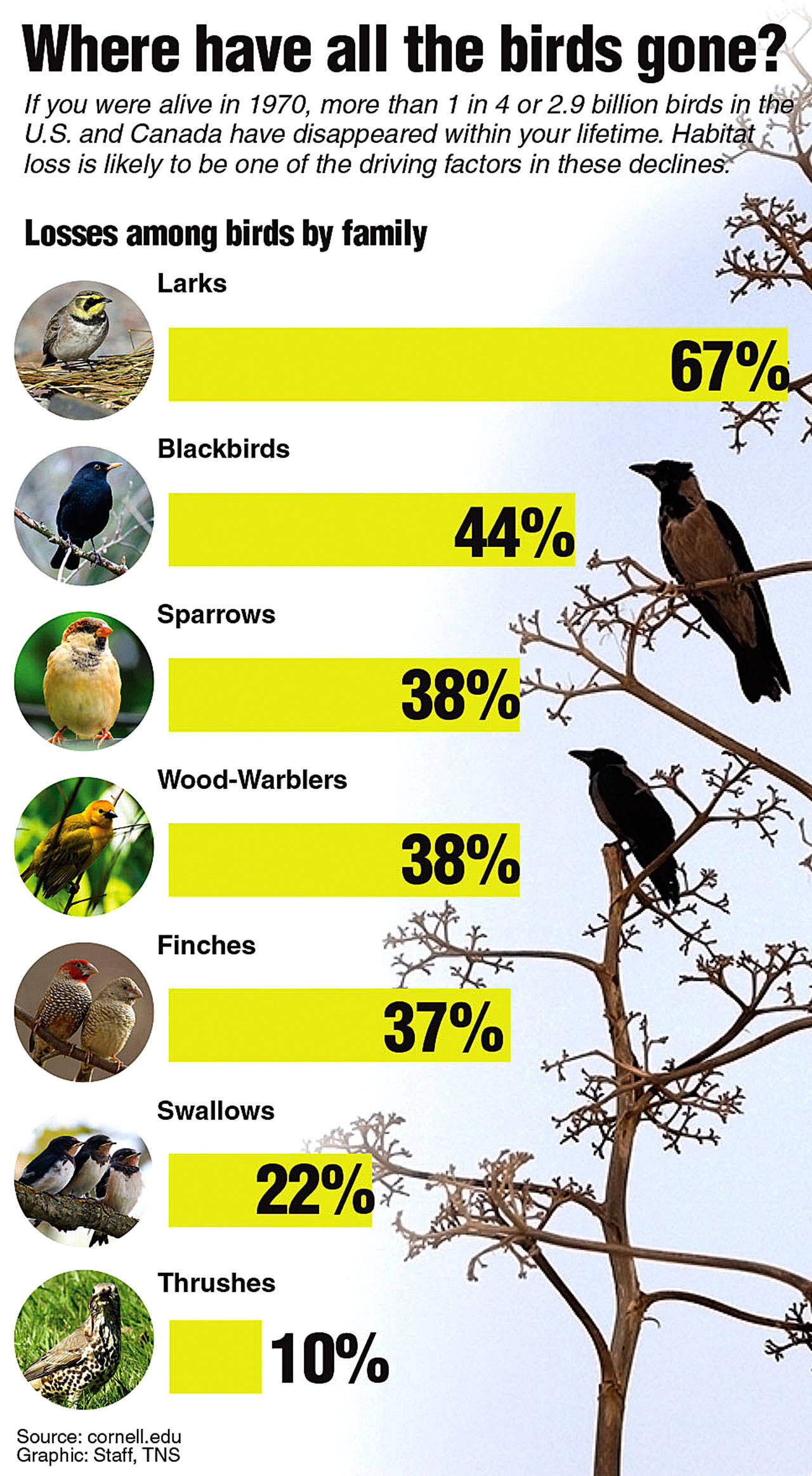

The data added up to a grim conclusion: Over nearly half a century, bird populations in North America had experienced a steep decline. There are 2.9 billion fewer birds today than there were in 1970 — a reduction of 29%.

Steven Beissinger, a conservation biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, called the results and their implications “dizzying.”

“I was pretty surprised,” said Beissinger, who was not involved in the study. “We don’t usually think in billions of birds.”

Of those lost birds, 90% come from just 12 bird families that include common and widespread species such as sparrows, swallows, warblers and finches.

Declines in the abundance of common species may not seem as dramatic as the endangerment of rare ones, but it is a very serious form of ecosystem erosion, the scientists said.

That’s because abundant species often play important roles in their biomes, whether they control pests, pollinate flowers, disperse seeds, provide food for other animals and even contribute to the natural beauty of an area that draws tourists who support local economies.

“When you’re losing abundance, you’re losing the fabric of the food chains, the fabric of the ecosystems — more perhaps than losing one rare species,” Rosenberg said.

Other formerly common species have fallen from mere loss of abundance to elimination.

Rosenberg pointed to the example of the passenger pigeon. Once it was probably the most abundant bird on the planet, but it was hunted into extinction by 1914. He added that the trend line of passenger pigeons’ losses looks similar to the trend seen in the new study, according to work by one of his coauthors, Jessica Stanton of the U.S. Geological Survey.

“Nobody ever thought the passenger pigeon would go extinct —and it did in a relatively short period,” Rosenberg said. “We’re not saying these other birds are on their way to extinction, but it certainly should give us pause and make us concerned that we’re seeing that level of decline.”

Across ecosystems, grassland birds — a group that includes sparrows and meadowlarks — were hit the hardest, the researchers said. Since 1970, their numbers have fallen by more than 720 million, representing 53% of the initial population.

More than 1 billion birds have been lost from all forest biomes. Shorebirds, long threatened by the draining of coastal wetlands and urbanization, saw declines of more than 37%.

The researchers did not weigh in on the causes for these declines. But other work has pointed to habitat loss due to urbanization, pollution, pesticides, and the intensification and expansion of agriculture as likely culprits, Rosenberg said.

There were a few success stories in the data that could offer a road map for aiding other bird populations, Rosenberg said. Wetland birds, such as ducks and geese, have increased, primarily because of conservation efforts that protected wetland habitats over the last few decades. (Much of that conservation was driven by hunters, who wanted to maintain healthy populations, he added.)

And raptors such as bald eagles, ospreys and peregrine falcons have also improved since the 1970s, when their numbers had been decimated by the use of the pesticide DDT. It was banned for agricultural use in 1972, and laws that protected the birds of prey allowed them to recover.

“It’s yet another example of resilience in the bird population itself if we can remove the threats and give them a chance,” Rosenberg said.

Such policies and protections need to be put in place for other birds in other habitats, the scientists said.

It’s hard to say what ecosystem services have been lost or degraded because of the loss of birds over the last half-century, Beissinger said. For example, if there were more birds around to eat bugs, farmers might be using less pesticide.