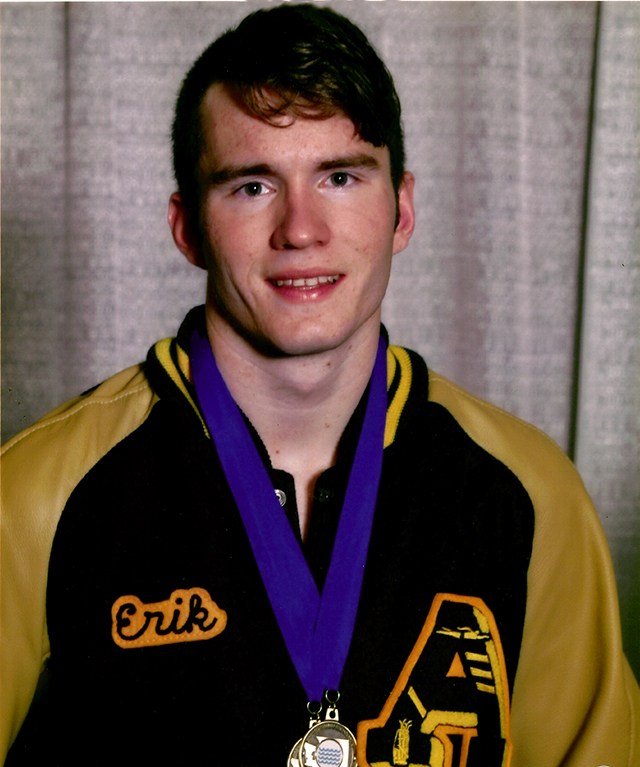

Editor’s Note: This is the third and final part of a multi-part profile of Aberdeen Mayor Erik Larson. Parts one and two appeared in Tuesday’s and Wednesday’s paper. The story was written by John C. Hughes, longtime editor and publisher at The Daily World and now the chief oral historian for the State of Washington. The profile is part of a series called Who Are We? and was written for the Legacy Project, an initiative from the Secretary of State’s office.

By John C. Hughes

Eleven months into Erik Larson’s four-year term as mayor of Aberdeen, the honeymoon was lingering, thanks in part to the novelty of his victory. Besides being young, 24 now but 23 when he was elected, and smart, he is simultaneously persuasive and respectful. WSU, his alma mater should be arriving any day now to shoot one of those “Go Cougs!” commercials. If he succeeds as mayor, some believe he’s a natural for the Legislature.

Larson has mixed emotions about all that. On the one hand it’s “Whoa!” On the other, he understands making hay while the sun shines.

“When I was elected there was a lot of media coverage, and a lot of people around here were thinking, ‘This is the most positive coverage we’ve received in a long time.’ But the story isn’t good unless I’m good,” Larson says. “So the media have to make me look good regardless of whether I am. While that lasts, I can leverage my age to spotlight some progressive things. So far, I think people have been happy at least with the attitude change, but I still have to prove myself. People will expect results — actual changes that you can see and feel and experience.”

One of Larson’s role models is Elson Floyd, the dynamic WSU president who succumbed to colon cancer in 2015 at 59. Floyd inspired people with his warmth, vision and unflagging civility, Larson says. “He made you feel important and led by example. At WSU I was part of a national civil engineering competition. Afterward, the university’s board of regents had their annual meeting and Dr. Floyd invited us to come and talk with them. He met individually with us before the event. What he projected was that he genuinely cared about every single one of his students. You can’t fake genuine like that.”

Larson’s authenticity may be his strong suit. He’s a good listener. He does his homework, understands the issues and avoids bureaucratic jargon. He’s unfazed by 16-hour days. Usually at work as an engineer by 6 a.m., he heads to City Hall around 4 p.m. and often has meetings that last past 9. “You could make a case that it’s an advantage for the city to have a mayor who’s only 24,” Larson says. “If I had a wife and kids, there’s no way I could maintain that kind of schedule. It would be an exercise in futility.” One thing is for sure: Larson is not in it for the money. Aberdeen pays its mayor $13,094 per year.

Larson is now getting his first chance to help write the city’s budget. He’s pushing for a city administrator, noting that Aberdeen is the only sizable city in the state without one. The City Council’s president is skeptical. Larson also wants three more police officers, two new corrections officers and a rental property inspector. The safety of the city’s rental-housing stock, wood-frame construction with ancient wiring, dating to the 1920s and earlier, is of great concern to the mayor and his fire department. More money for abatement of derelict properties is another of Larson’s priorities. These steps will require no hike in utility or ambulance rates, Larson assured the council.

Another intriguing development is that Aberdeen, Hoquiam and Cosmopolis — Siamese triplets joined at the hip — are once again exploring the possibility of consolidating some key services. The idea has been raised practically every 20 years for a century. In the 1970s, in fact, Aberdeen and Hoquiam briefly consolidated their police departments before the plan ran afoul of bureaucratic snafus that slighted Hoquiam. But Hoquiam now has a new young mayor of its own, 30-year-old Jasmine Dickhoff. And budget challenges. Public safety concerns are paramount for the leaders of all three cities. “It is imperative,” they wrote in support of a comprehensive new study, “that we have a unified emergency management system that is responsive to both the day-to-day public safety needs of our communities and to the increasing challenges posed by rising costs and diminishing revenues.”

Fixing downtown

Mayor Larson has high hopes for a proposed new tourist information and job-creation “enterprise” center at the west entrance to downtown. For better or worse, Aberdeen’s main streets are also the state highway that funnels traffic to and from the beaches and the upper Olympic Peninsula. Downtown Aberdeen has been so threadbare for so long that there’s little incentive for those panzer divisions of clam diggers and campers to stop and shop. New sidewalks, street lamps and hanging baskets brighten the corridor, but visitors still see vacant storefronts and, lately, a boarded-up, cut-rate motel that was home to an array of unsavory goings-on until the city and the Health Department forced its closure.

Look more closely, however, and you’ll see the “good bones.” Larson believes the rehabilitation of the city’s landmark Morck Hotel and the construction of the “Gateway Center” could be the catalysts for a comprehensive revival of the city’s historic downtown core. Built in 1924, “the Morck” was a source of civic pride until, like the Davenport in Spokane and the Marcus Whitman in Walla Walla, it lapsed into seediness in the late 1960s. An ambitious renovation plan was derailed by a partnership dispute in 2007 and further stymied by the recession. The summer of 2016 brought signs that the project could be back on track. That would be a huge civic morale builder, Larson says. “Having a quality hotel as the hub of the city is important to our future.”

Grays Harbor always seems to be tantalizingly on the verge of landing a new industry or major business. It’s always one step forward and two back. Lately, the visionary yet mercurial investor who plowed major money into the historic D&R Theater and other downtown buildings has been sparring with City Hall over perceived slights.

Larson seems unperturbed. He refuses to let past history, foot-dragging and “predictable setbacks” dampen his enthusiasm. When he surveys his city he sees opportunity on practically every corner.

Creating a Climate for re-investment

The stately Becker Building, the city’s tallest, stands virtually vacant a block from City Hall. “It’s a jewel with all sorts of potential,” the mayor says, emphasizing that the city needs to create a climate that promotes re-investment. “We haven’t seen much major investment in Aberdeen since about 1960. All of the major buildings that comprise our retail infrastructure are old. That’s a costly problem. Many are negative equity properties. If you paid a dollar you’d be paying too much. The remediation costs and upkeep costs are so high that it completely wipes out the project value. From a government standpoint, you look around and realize you’ve got all of these properties on your tax rolls that are worth negative dollars. Nobody’s going to invest in them and create opportunities until we can get that at least to zero. Somebody’s going to have to make up that difference — whether it’s the city or the county or the state and federal government providing funds to help mitigate that. I’m not saying we should throw good money after bad, but if making the city more livable is important, we’re going to have to face real-world realities and find ways to promote re-investment.”

Engineering mind

Larson’s engineering mind envisions progress as a series of interlocking pieces, like rebar and girders. A new flood-control project is the foundation for much of what he envisions. Aberdeen and its west end are built atop dredge material and sawdust spaltz — scraps from lumber and shake mills. In the 1890s, rough and tumble Aberdeen was known as “Plank City.” Wooden sidewalks rose and fell with the tides. Over the past 40 years, storm drain and levee projects have reduced flooding in the low-lying areas along the Chehalis, Wishkah and Hoquiam rivers. But Aberdeen still averages 84 inches of rainfall annually. A January storm at high tide can leave the city wet past its ankles. Sand bags are on standby all along main street.

Flood insurance has emerged as a major problem for Aberdeen and Hoquiam. The bureaucratic snafus that emerged from Hurricane Katrina caused flood insurance costs to skyrocket nationwide. The premiums are now at mortgage-level rates for folks in the blue-collar west end of Aberdeen. And you can’t refinance or secure a home-improvement loan without buying flood insurance—sometimes twice as much as the house is worth. Aberdeen and Hoquiam are working with their congressman, Derek Kilmer, to secure funding for a comprehensive flood plain management program. “In certain areas we’ll have new earthen levees, with a waterfront boardwalk,” Larson says. “There might be areas where we’ll build a seawall or an aesthetically attractive, textured concrete wall to protect against the storm surge. And here’s what’s so important to future development: If you build a levee and get it certified, the flood insurance requirement goes away. I have people contacting me seeking help as the cost of flood insurance rises. It’s a big impact on home ownership. I can’t force the banks to give them a loan. I can’t tell FEMA or anyone else to let them rebuild their homes at the current level. So it’s frustrating — heartbreaking in fact. Until we fix that issue, we’re not going to see any significant development.” Larson and the City Council hope the voters will recognize that the cost of the bonds to build a levee will be less than the rising tide of flood insurance.

Larson and the staff at City Hall also are working with state agencies to ensure that the site where the pontoons for the new Lake Washington SR 520 floating bridge were constructed remains viable for another industry.

Though the area badly needs more jobs, the Aberdeen City Council unanimously adopted an ordinance banning crude oil shipments. The companies pushing the hotly debated plan are wooing Grays Harbor “because nobody else will take them,” Larson says. “This wasn’t their first choice, both for cost and environmental impact. And I don’t think it’s the best use of our rail capacity. We’ve already had a major oil spill in this area. Is this a great place to transfer oil through? A place that intersects wetlands? Probably not. You’d never be able to contain a major spill because the current in the rivers is too fast. By the time you deployed containment it’s already in the bay. At the first low tide it’s going to get in the mud. And you’re never going to get it out. Would it create enough jobs and revenue to offset the risk? Probably not, in my mind.”

The controversy over oil trains has overshadowed the importance of rail to Grays Harbor’s future, Larson says. Rail, unquestionably, is a crucial piece of the infrastructure that has spurred the Port of Grays Harbor’s rebound from the recession. “A lot of people feel the railroad isn’t making enough investment in the Harbor area. But most people don’t understand rail in general,” the mayor says. “They’re spending tons of money, and they need our support to replace some of their infrastructure. If that rail line goes down, we’re done. If we don’t have rail access to our port, the port’s finished. And if the port’s finished, it would be the death knell.”

‘Quality of Life’

It’s often said that “quality of life” begins with a decent job. The challenge facing Mayor Larson and the City Council is to leverage the Harbor’s natural assets — and affordability — to spur investment, without compromising the environment. Long gone are the days when Harbor-area folks characterized smokestack stench as “the smell of jobs.”

Most of the hundreds of thousands of visitors who pass through Aberdeen every year can’t see beyond the downtown grunge, Larson says, yet in the immortal words of Joni Mitchell Seattleites have paved their own paradise and put up a parking lot. Larson’s 15-mile “commute” to his job near Montesano is a lark while Puget Sound is gripped by gridlock. And the average house there costs $500,000.

“A lot of people are getting tired of all that — especially people who want to buy a home and raise a family,” Larson says. “Increasingly many people are able to work from anywhere, and we can provide the quality of life they yearn for. We’re going to attract new business for the same reason if we create the right incentives. But you can see the big ones by just looking around: The beaches, the rain forest, the natural beauty of the area. We’re going to be well positioned for the future if we work together and invest in our city.”

Back at the duck blind, Larson nearly has his limit by 10 a.m. Then he and his brother help their dad collect crab from the pots they placed in the bay two days earlier

For the mayor of Aberdeen, a perfect fall Sunday ends with a Seahawks game on TV at his house, with a few friends and a growler of local brew.

He doesn’t have to say, “Come as you are.” In Aberdeen that’s understood.