By Deborah Netburn

Los Angeles Times

In the search for life beyond Earth, humans have sent robots to the rocky surface of Mars, deployed spacecraft to investigate the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, and aimed their most powerful telescopes toward distant solar systems.

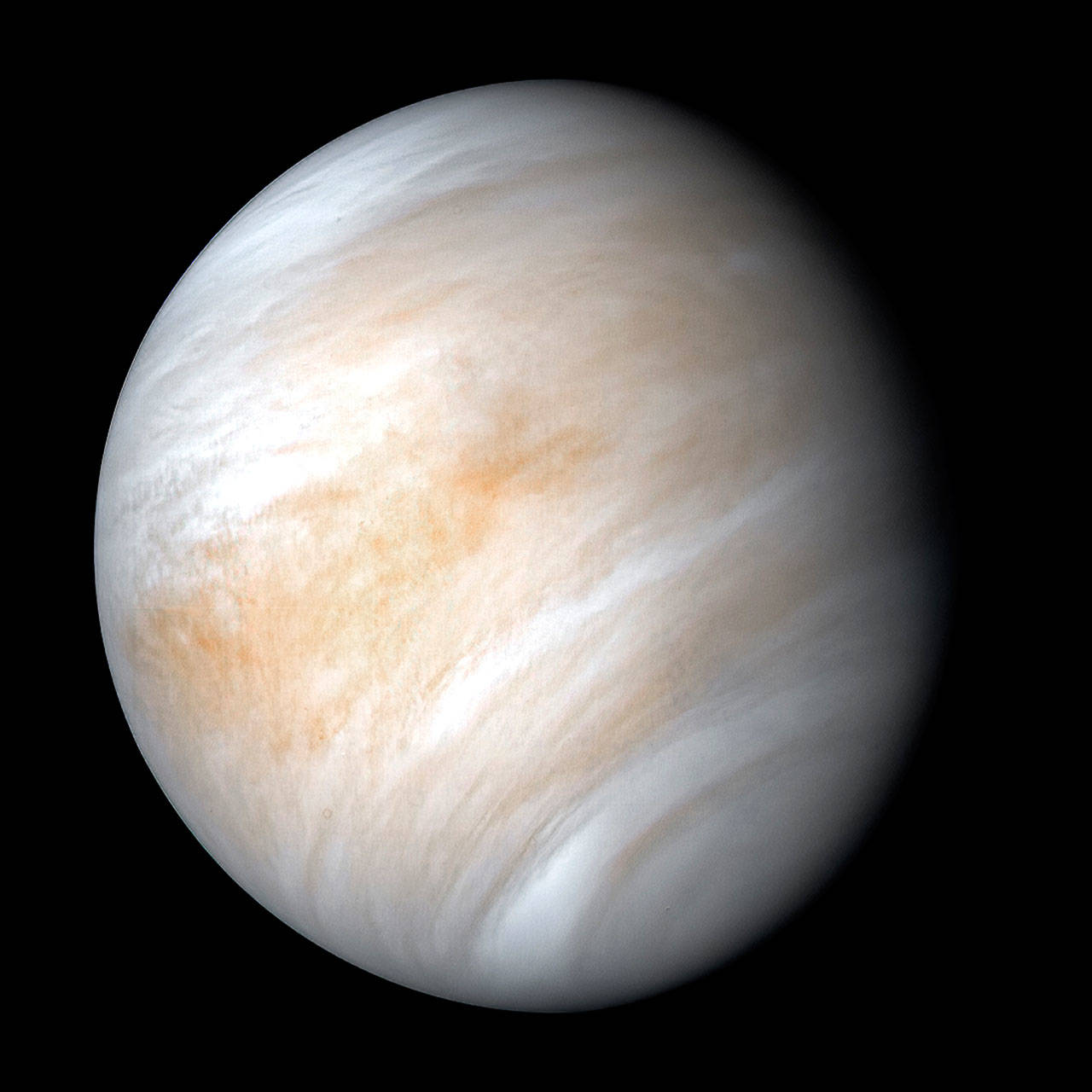

But now, in an unexpected twist, a group of scientists say they have found possible signs of extraterrestrial life in a place where few had thought to look: high in the thick, toxic clouds of Venus, our closest planetary neighbor.

In that noxious environment, they discovered a gas called phosphine that is associated with life on Earth.

The notion that the Venusian phosphine could have been produced by living organisms may seem absurd, the team members acknowledged. And yet it’s one of the most plausible theories they have.

“There are two possibilities for how it got there, and they are equally crazy,” said Massachusetts Institute of Technology astrobiologist Sara Seager, a member of the team that reported the discovery Monday in the journal Nature Astronomy. “One scenario is it is some planetary process that we don’t know about. The other is there is some life form living in the atmosphere of Venus.”

Seager emphasized that she and her colleagues are not claiming to have found evidence of life on Venus. Instead, they are saying they found a robust signal of a gas that doesn’t belong in the planet’s atmosphere, and that it will take a lot more work to understand how it got there.

“What we need now is for the scientific community to come and tear this work to shreds,” said Clara Sousa-Silva, a molecular astrophysicist at MIT who worked on the paper. “As a scientist, I want to know where I went wrong.”

Phosphine is a pyramid-shaped molecule with a phosphorus atom on top and three hydrogen atoms at the base. It is hard to make on rocky planets like Earth and Venus because it takes tremendous pressures and temperatures to get the atoms to bond, Sousa-Silva said.

Those conditions exist deep within the interior of the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, but rocky planets like Earth and Venus simply don’t have the thermal environments that would allow phosphine to form spontaneously.

On Earth, the production of phosphine is associated with anaerobic life, which does not need oxygen to survive. It has been detected in marshlands, rice fields, sewage plants, animal feces and the intestinal tracts of fish and human babies, Sousa-Silva said.

Sometimes it’s a byproduct of shoddy work in meth labs, and it has been used as a pesticide and an agent of war.

“I love phosphine, but I would never want to be in a room with it,” Sousa-Silva said. “It is extremely toxic. Very few people have smelled it and lived.”

Because phosphine is associated with life on Earth, scientists such as Seager and Sousa-Silva thought it might be a biosignature of life on other rocky planets as well. “I considered a huge array of places we might look for phosphine, but I never considered looking next door,” Sousa-Silva said.

Although Venus is our closest neighbor, it has remained a pretty fringe place to look for signs of life. Its surface is uninhabitable for life as we know it, with temperatures of up to 900 degrees Fahrenheit and bone-crushing atmospheric pressure up to 90 times higher than that of Earth.

Scientists think Venus may have once had oceans of liquid water that boiled off at least 1 billion years ago. Today, its surface is far dryer than anywhere on Earth, and its atmosphere consists mostly of carbon dioxide, with clouds of sulphuric acid.

Despite these hellish conditions, a handful of scientists since the 1960s have argued that life could exist in a region 30 miles above the surface, where temperatures and pressures are similar to those on the Earth’s surface, and where small airborne organisms could possibly survive.

“It’s a very fertile environment,” said David Grinspoon, an astrobiologist and senior scientist with the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, who was not involved in the study. “The cloud droplets provide an aqueous environment; there are nutrients and other elements you need for life and plenty of energy sources.”

One potential scenario is that life evolved on the surface when Venus still had oceans, then migrated to the clouds as the planet grew warmer over time. This life would likely be microscopic and perhaps similar to some forms of bacteria that spend part of their lives in the ephemeral clouds on Earth.

Jane Greaves, an astronomer at Cardiff University in Wales and lead author of the new study, knew that the clouds of Venus had been suggested as a potential habitat for life and that phosphine could signal the presence of life on rocky planets. So she put two and two together and set out to search for phosphine in the small band of Venus’ atmosphere that just might be habitable.

“I was specifically looking for signs of life,” she said.

Greaves is a radio astronomer who had worked in the ’80s at Hawaii’s James Clerk Maxwell Telescope. In early 2017, she called up Jessica Dempsey, the telescope’s site director, and asked if she could do something crazy. Then she presented her plan.

“I said, ‘Of course!’ ” Dempsey said. “You are not going to find what’s possible if you don’t try the impossible.”

Greaves got a total of eight hours of viewing time over five mornings in June 2017, but it wasn’t until the end of 2018 that she was finally able to take a close look at what the telescope had seen. It took several months to tease out a detection of phosphine from the noisy data, but eventually she found it.

Dempsey vividly remembers the day she received an email from Greaves with the detection spectra.

“I just sat there, blinking at the screen,” said Dempsey, who wasn’t part of the study team. “When I regained the power of speech, I gave her a call and said, ‘You just blew my mind. Am I really seeing what I think I’m seeing?’”

A second observation in March 2019 with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile confirmed the discovery.

Greaves’ next step was to find phosphine experts who could help her determine whether the gas really did represent a potential sign of life on Venus. A mutual friend led her to scientists at MIT.

“My first reply was, ‘Are you absolutely sure?’” said Sousa-Silva, who had recently written a paper explaining why phosphine could be a biosignature in exoplanet atmospheres. “Because it’s not just weird. It’s really weird.”

Over the next several months, the MIT team explored every chemical process they could think of that had the potential to generate phosphine on Venus without the aid of life.

When they incorporated lightning and meteor strikes into their models, they determined that phosphine could be produced on Venus —but only in amounts that were a tiny fraction of what Greaves had found. Besides, phosphine should degrade in the atmosphere, but the steady amount suggests that it’s being constantly replenished.

In desperation, they considered whether tectonic activity might have driven the production of the gas.

“We don’t even think that there are tectonics on Venus, but it still seems less crazy than aliens,” Sousa-Silva said.

Ultimately, they could not find a plausible explanation for the presence of phosphine that did not involve some sort of life form.

But that doesn’t mean there isn’t one, said Matthew Pasek, an astrobiologist at the University of South Florida who was not involved in the work.

“It definitely bears further inquiry,” he said. “My guess would be there is some non-biologic process that is making it, but they certainly found something weird.”

Pasek added that scientists still aren’t sure how life on Earth produces phosphine, or if it is made by organisms at all.

“We believe it is biological, but we don’t have proof of that yet,” he said.

The study’s authors agree that there is much more work to be done. They hope their findings will inspire more scientists to study phosphine. They also hope to spend more time characterizing the phosphine on Venus to find clues about how it got there.

Sending a spacecraft to Venus would be helpful. NASA has two Venus missions currently under review.

But all of this will take time. It could take years or even decades to prove conclusively whether there is life in the Venusian clouds, Seager said.

“We have a long road ahead of us,” she said.

———

(c)2020 Los Angeles Times

Visit the Los Angeles Times at www.latimes.com

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.