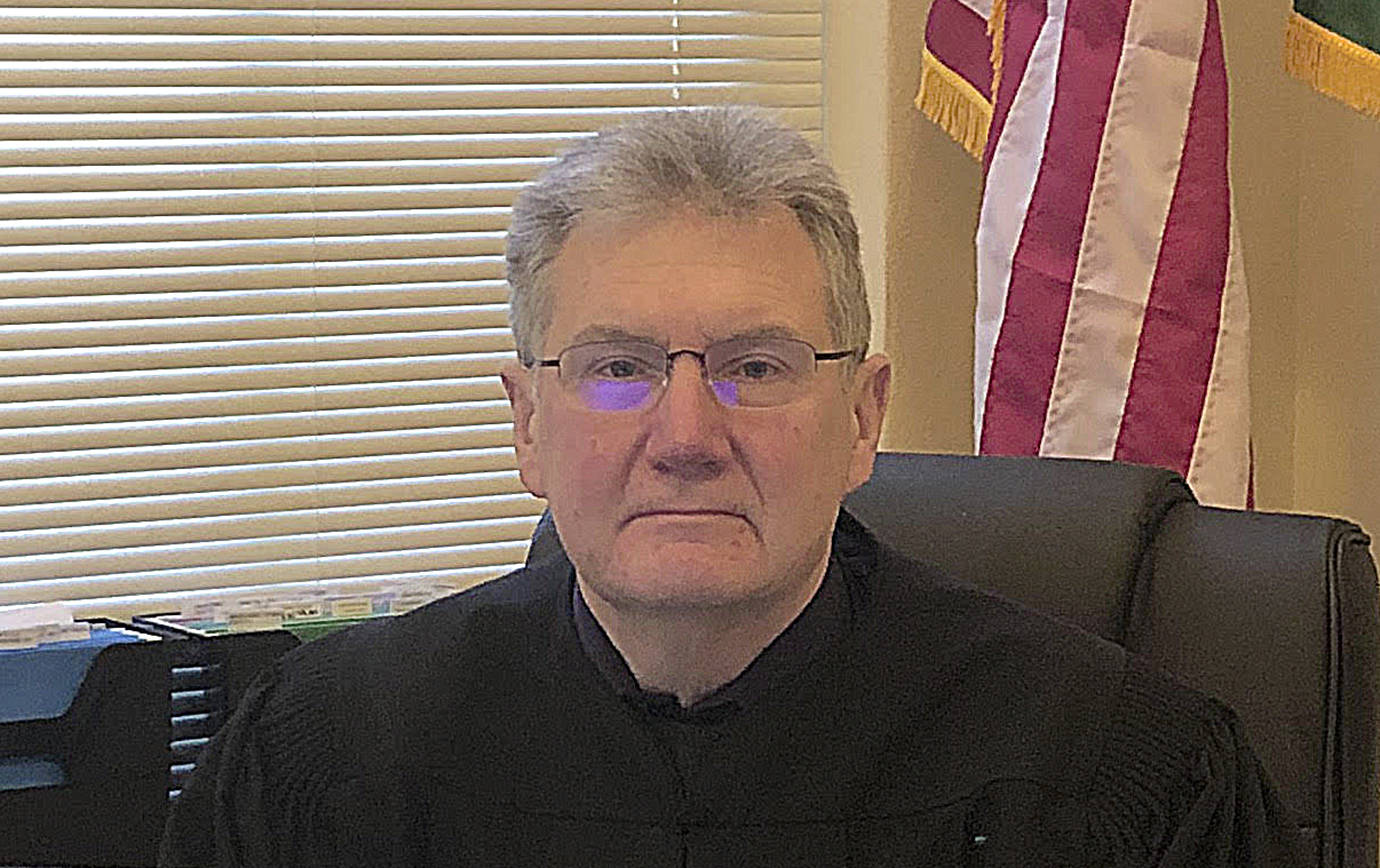

When he was sworn in as Grays Harbor County Superior Court judge in 2014, Stephen Brown offered a list of “future goals/ideas/directions.”

Among that list, “I would like to see a drug court in Grays Harbor County.”

In April 2018, that drug court opened in a tiny courtroom at the Grays Harbor Juvenile Detention Facility. To date, the court, which offers offenders of drug-related crimes a way out of the cycle of substance abuse and jail, has graduated 23 clients, according to court coordinator Jamie Wintrip.

Brown is retiring after 40 years of service to the county, starting as a deputy prosecutor in 1980. His legacy will be the therapeutic courts — the successful drug court and the recently formed family recovery court.

Brown said one of the main reasons he aspired to the Superior Court bench was “to hopefully be able to provide the leadership necessary to introduce therapeutic courts in the county. It took a while, it didn’t happen overnight, and there were a lot of different stakeholders we had to work with, but we kept at it and were able to get everybody on board eventually, and once we got it gong it started to sell itself.”

The family recovery court “is for parents with substance abuse disorders whose children were taken into care,” said Brown. He said once the drug court was created and operational, “it made it a lot easier to extend it to family recovery court.”

Brown said of the family recovery court, “It’s a different program. They’re not offenders, not accused of any criminal behavior. It’s a different process but still the same. We’re trying to support them as human beings in their recovery, because if you truly engage in recovery and go through the program, chances of further behaviors that impact our child welfare system and criminal justice system are reduced.”

The commitment outside the courtroom to get both courts up and running was significant, but important to Brown.

“I just saw that it worked throughout most parts of the state,” said Brown. “And with my training and upbringing I try to look at people as human beings and try to get good outcomes for people in their lives.”

He’s seen the devastation of addiction in his courtrooms for years, and has long been a proponent of the way out therapeutic courts offer.

“The criminal justice system is oriented mostly around punishment, but people get into this cycle with a substance abuse disorder and lose everything. Their family, the means of support, housing, transportation, employment, all goes away,” said Brown. “Programs are provided and it works for some people — it’s not that the system has failed everybody — but when you add this long term substance abuse problem on top of it and the justice system has struggled to deal with these issues.”

Therapeutic courts are a kind of cross between criminal justice and looking from a disease point of view.

“If you don’t treat the disease it’s kind of hard to change behaviors,” said Brown. He said he didn’t “invent the wheel” when it came to these types of courts, they exist throughout the state, “I thought it would be good for the county and I got a lot of feedback from others that they would like to see it in the county, so that’s kind of what got me on that.”

Fellow Superior Court Judge David Mistachkin took over the drug court from Brown in October, and shared his thoughts on his colleague.

“Judge Brown has worked tirelessly throughout his judicial career to promote therapeutic courts including drug court and family recovery court,” he said. “Judge Brown spearheaded this effort and thanks in large part to his hard work, we have these fully operational and successful therapeutic court programs.”

Mistachkin continued, “I admire all his hard work and want to congratulate him for his success. I have enjoyed working with (him) and have always found him to be amenable to discussing issues with the court and about how we can improve court operations. He’s always been very conscientious in his efforts to promote full and fair adjudication of matters before him.”

“He has a great work ethic and undertakes tasks that are complicated and works them through to completion. A good example of that is drug court,” said presiding Superior Court Judge David Edwards. “That’s his baby. I can’t begin to tell you how much effort he had to put into getting all of that organized, funded, implemented, staffed, he did it all, and he did it well. The success of the program speaks to that.”

Prosecutor Katie Svoboda, who will assume Brown’s spot on the bench Jan. 11, said she was “sad I’m not going to get a chance to work with him on the bench. In my appearances in front of Judge Brown I never thought somebody had the advantage because of who they were, or who the lawyer was. His decisions are based on the facts in the law and not on things that shouldn’t be considered. I think he’s a man of integrity and intelligence and I like him very much as a person.”

“He’s great to work with, a great leader, always seems dedicated and motivated to what he was doing,” said Wintrip, the drug court coordinator. “He had a way of caring about the participants in our program. I hope he understands how much of a part he played in changing their lives.”

Wintrip said when she conducts exit interviews with drug court participants and asks what was the most important and impactful part of the program, “I hear time and time again that the encouragement from Judge Brown meant the most.”

One graduate wrote to Brown, “You had faith in me when I did not have faith in myself. None of this would have been possible without the encouragement you gave me.”

Brown grew up around legal service to Grays Harbor County. His dad, Ed Brown, served as City of Elma attorney, was a deputy prosecutor in the county and was elected county prosecutor in 1962, serving in that position until 1974. After that he served as a district court judge until he retired in 1986.

Even with that pedigree, as a young man, Brown wasn’t dead set to follow in his dad’s footsteps.

“I didn’t obsess over it or anything, I kept my options open when I went to college,” said Brown, adding the legal career simply “turned out to be the career path I wanted to do.”

Brown started off as a deputy prosecutor in 1980 and continued into law practice in Elma and Montesano. When he was just 28 years old, he served as a judge in the Elma Municipal Court, and was elected, at age 31, to the district court in 1986.

He lists as his mentors Curt Janhunen, who hired Brown as deputy prosecutor right out of law school, and Judge Tom Parker, whose courtroom Brown was assigned to when he was deputy prosecutor.

Now 65, Brown said he’s looking forward to spending more time with his family, but won’t be completely out of the game. That list of future goals/ideas/directions he offered at his swearing in as Superior Court Judge also included, “I support expanding the use of voluntary mediation and other alternative dispute resolution processes in Superior Court cases.”

“I’m looking forward to actually becoming a certified mediator through out local dispute and resolution center,” he said. “I’ll hopefully be able to help people reach their own resolutions” rather than court-imposed resolutions. “It will keep me engaged a little, but it’s not a full time job, and I think I can help, especially with my experience.”

And by the way, a third item on that list of future goals was, “It would be great to actually get that third Superior Court courtroom.” That third courtroom was open for business in August 2018, and Brown handled the first case in that courtroom, an adoption.