By Virginia Heffernan

Los Angeles Times

When Nebraska Sen. Ben Sasse addressed the Senate on Jan. 6 just after the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, he said grandly, “America isn’t Hatfields and McCoys, blood feud forever.”

Oh no? I wish C-SPAN had cut to the face of West Virginia Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin III. The people of Appalachia don’t always take kindly to Hatfield-McCoy references. At least my Appalachian mother, a proud daughter of McDowell County, W.Va., texted me to scoff.

“Of course we are a nation of Hatfields and McCoys,” my mountain mama said. “What country is this flatlander Sasse living in?”

Like the iconic warring families of the Civil War era, today’s political feuders seem hellbent on prosecuting nonsense grudges at any cost. Coca-Cola boycott anyone? If any nation is a pitched battle with hostilities that seem intractable, it’s America of 2021.

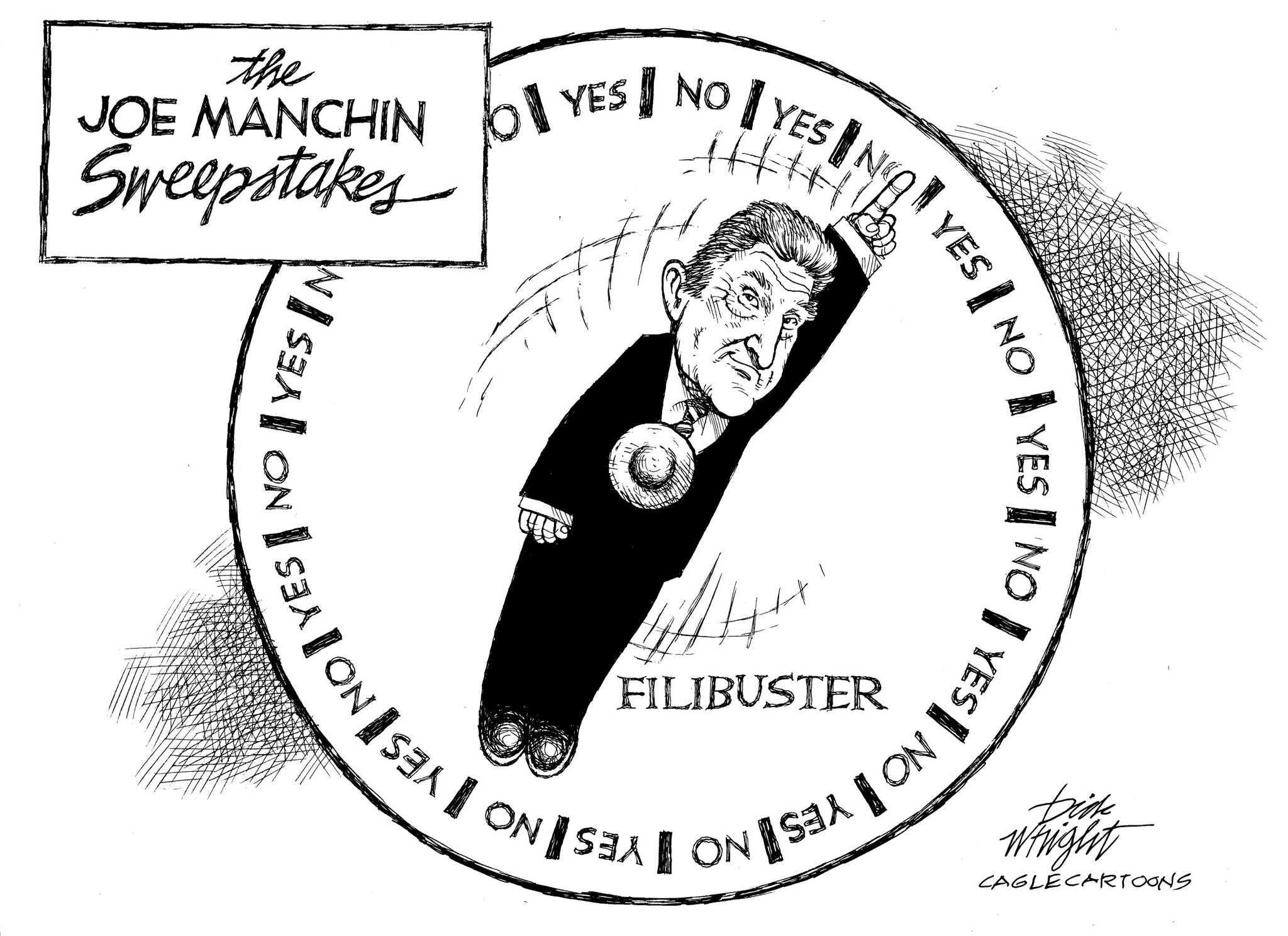

Which brings us to Manchin, sometimes a deciding Democratic vote and therefore arguably the most influential senator in the country. He’s also the Democrat whom Democrats most love to hate for his obstruction to President Biden’s agenda.

As maddening as he is, his bipartisan triple axel is impressive. How is it even possible that Manchin serves as a Democrat in deep-red West Virginia, which votes Republican 19% more often than the country does? He’s like a McCoy repping a Hatfield state.

The surprise shouldn’t be that Manchin sometimes votes with Republicans (32.6% of the time during the 116th Congress). The surprise is that fully two-thirds of the time he votes with Democrats. To call him a DINO is erroneous.

If Democrats want a more solid majority, they need to vote more Democrats into the Senate. In the meantime, Manchin is an important centrist voice — and not because he advocates for a bland, Sasse-ian utopia of good manners, but because he’s a political code-switcher who deeply understands both his constituency and the issues.

So how’d Manchin get here? He has had own story, and, like all good Appalachian stories, this one is out of sync with the rest of the country.

Manchin, first off, is from Farmington, a town in the coal fields, where commitments to fossil fuels and the working class were once of a piece.

Manchin has stuck, roughly, with both of those positions though partisanship claims to pull them apart. He supports the Affordable Care Act while opposing most green energy policies.

More recently, Manchin objected to increasing the federal minimum wage to $15. That would seem to punish workers, until you consider that West Virginia, the sixth-poorest state in the country, currently has a minimum wage of $8.75. Raising it by a full $6.25 could drive out employers and push up poverty even higher.

On guns, he’s also all over the map. In 2004, he got an A from the National Rifle Association. In 2018, after he sponsored a background checks bill, the NRA gave him a D.

Manchin’s politics are eccentric, eclectic, inventive and unpredictable. Like his state. (Like my mother.)

Christopher Regan, former vice chair of the West Virginia Democratic Party, recently argued in the Atlantic magazine that Manchin is singular in the Senate — a bill-by-bill, issue-by-issue tactician, one who carefully calculates the electoral popularity of every decision he makes. You don’t thread tight needles by not paying attention.

The motto of the state of West Virginia is Montani Semper Liberi. “Mountaineers are Always Free.” Unlike other states with mottos that stake a claim to freedom — New Hampshire’s “Live Free or Die,” say — Montani Semper Liberi is not aspirational. It’s descriptive.

If you live in hollows and small towns tucked into nearly unpassable mountains, it’s still an ordeal just to get electricity and newspapers, and forget about cable TV, Wi-Fi and the memes that come with those things. Rural West Virginians are less beholden to, and also less served by, utilities, dominant culture and governments. This strandedness looks dangerous to many. To others, including plenty in my family, it looks like freedom.

Manchin can be a tonic for the polity. In the social sciences, “cross-cutting issues” are often seen as a sign of the health of a political discourse.

Individual lawmakers with Manchin’s bent, who hold views across cultural lines — make partisans nervous. But they’re excellent for confounding the rigid antagonisms that keep a country locked in us-and-them battles whose reason for being was lost long ago.

At bottom, Manchin is not the one who keeps such nonsense battles alive. The Hatfield-McCoy vibes are pumped now by outrage factories like Fox News and One America News. Coca-Cola, Dr. Seuss, baseball? Surely none of this trivia gets much traction in Farmington (population 445) or my mother’s hometown of War (population 760).

Public health has long been a concern of West Virginia lawmakers, who for decades have addressed deadly plagues, from black lung to opioids. Manchin reserves his Twitter feed for #MaskUpWV, defending Anthony Fauci and crowing, justifiably, about the first-rate vaccine program in West Virginia. In West Virginia as of Thursday, 21.5% of the population is fully vaccinated. (It’s 18.8% in California.)

Manchin is never going to look like a California Democrat. But he doesn’t look like a California Republican either. I’d almost say that, as a politician, he’s nonbinary, and that’s a good thing — but I fear that word would set off the Hatfields or the McCoys or both — on Newsmax.