A quarter-century ago, Lt. Jim Davis of the Ocean Shores Police Department went into the water near the north jetty in Ocean Shores on a routine surf rescue call on a Sunday morning.

Davis didn’t return. He gave his life attempting to save another that morning.

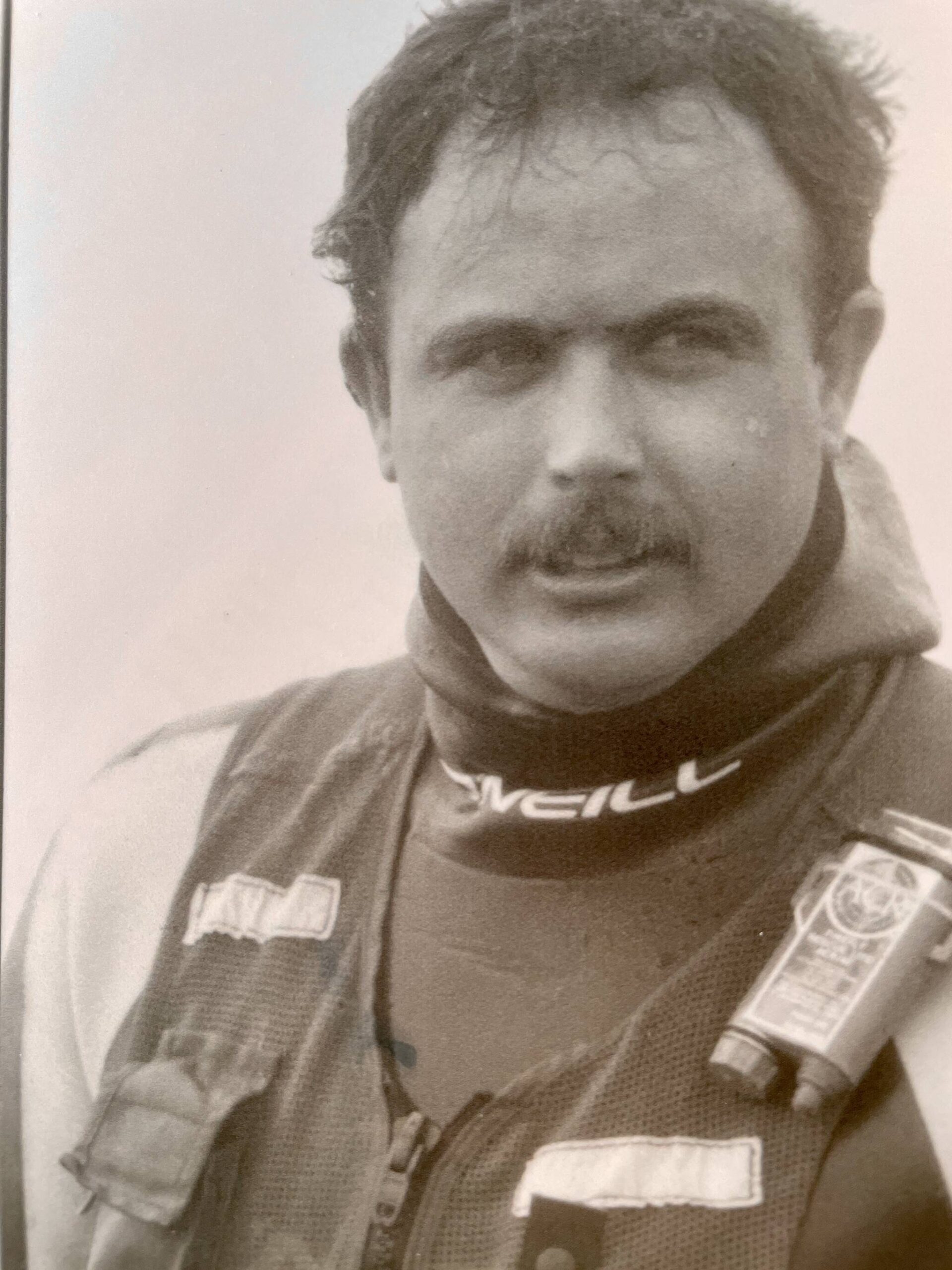

The recently-promoted lieutenant and team leader for the surf rescue team, Davis had performed dozens of rescues, receiving multiple commendations over the years. The call, for a 26-year-old surfer in distress, wasn’t particularly unusual in the beginning.

“He walks out the front door,” recalled Davis’ son Travis about that day, now the chief corrections deputy with the Grays Harbor County Sheriff’s Office. “He’d been out on a million of them. He always came back.”

The cause of death was listed as drowning, Travis said. Punishing heavy seas and mechanical malfunctions helped compound a rapidly deteriorating situation.

“The rapidity in which it all went to hell… typically, it’s go out, grab the guy, motor in, you’re done,” said Lee Fundenberger, who was a member of the team and a fire captain/paramedic with the Ocean Shores Fire Department at the time of the event in 1998. “It took minutes. It went from a nice day out here, we’re having fun, to ‘oh, crap.’”

Davis was 42 at the time of his death, attempting to claw another life back from the ocean’s grasp. The Daily World sat down and talked to members of his team and family, painting a picture of a man who enjoyed his job, his family, and his community before his death.

A life lived fully

A lieutenant, a detective, a DARE officer, an assistant football coach, Davis was known around town, a personable, down-to-earth man who knew how to talk to people and who believed in the community.

“(Davis was) a bit of a jokester. Good to work with,” Fundenberger said. “When he said something, you knew he meant it.”

A binder of clippings and photos compiled by the family opens with a stack of copies of awards, citations, certificates that tell of a straightforward life, first in the Army, then in the police service.

“My dad was in the military,” Travis said. “I remember as a young kid being in Colorado, being outside of Denver somewhere.”

Combat Arms Noncommissioned Officer Academy. Basic military policeman course diploma. Army Commendation Medals. A wry “certificate of depreciation,” talking about a 10-month rotation Davis did in Korea in 1978, laden with good humor about the assignment. Separation from service— an honorable discharge. His DD-214, detailing time as an artilleryman, and then a military policeman.

Then law enforcement. Basic law enforcement academy, from the Spokane Police Department. A letter of commendation after someone he stopped for speeding wrote in to laud his professionalism. Training certifications from the State Patrol. Certificates of approval. Supervisor qualifications. DARE class graduations. Initially from Spokane, and then from the Ocean Shores Police Department.

“We moved here, it was, 8th grade, ‘88 or so,” Travis said. “I was told we were moving to the coast, and I was like, why are we moving to Seattle?”

A school board election certificate. Letters of appreciation from same. Copies of old camera film, showing Davis with a working dog. Newspaper clippings from the formation of the surf rescue team— “It’s not Maui.” Pictures of Davis assisting with the rescue of a family from a flooded house.

“Jim was good at the investigations game,” Fitts said. “He knew how to play the game, with the right attitude with the right people.”

And then articles from after the event. Medal of Valor, posthumous award. Communication printouts from departments across the country, sending condolences. From Cosmopolis. From the King County Sheriff’s Office. From a department in Oklahoma. From the Chief of the Dallas Police Department. From the Delaware State Police. From NCIS. From dozens more agencies.

A collection of photos of signs from around Ocean Shores— an outpouring of grief from business and churches. Some just a few words, many more personal. Davis’ death deeply wounded Ocean Shores.

Surf rescue team

The surf rescue team was initially primarily drawn from the police department, Fundenberger said.

“I was the only fire member on the surf rescue team. The rest were all police,” Fundenberger said. “It was the mid-’80s. I was a paramedic by then.”

The team trained hard, and every time the departments got a call about someone in distress in the water, they’d go out.

“I started out here in Ocean Shores. I moved here from Southern California in 1991-ish,” Iversen said. “I joined the fire department as a volunteer firefighter and first saw the surf rescue team in action. They were like superheroes.”

A lot of the police joined for different reasons, said Russ Fitts, another member of the team who was on the rescue that day.

“I was a lifeguard in high school. I knew how to surf and scuba dive. I loved the water,” Fitts said. “Law enforcement, you can help people, but it’s usually after the fact.”

Surf rescue was an opportunity to help people directly, saving lives in an unambiguous and clear-cut way, something Davis reveled in, Fundenberger said.

“It wasn’t dangerous police work, repetitive police work- it was a new challenge. He really enjoyed it,” Fundenberger said. “Turned into a kid again.”

That enthusiasm for straightforward lifesaving was shared by many of the other police.

“I was like, wow, I actually saved a guy’s life. That’s better than any murder suspect I ever arrested or any rapist,” Fitts said. “Regrettably, most of the calls we got were after the fact.”

Fitts recalled getting an inflatable shark fin to mess with Davis with.

“It was a great group of guys. Jim was fun because Jim had an aversion to sharks,” Fitts said. “We’d be out training in the surf lane and something would bump your leg, and then a seal’s head pops up.”

The surf rescue team trained hard, Fitts said. From the outset, they were busy, with the first call they responded to coming on their very first day of training, Fundenberger said.

“A lot of time, just swimmers— they go out and do not understand what a rip current was, how it was generated and how to get out,” Fundenberger said. “The public at that time wasn’t educated about rip currents.”

Oceans Shores has powerful rip currents, especially near the north jetty, where they can make it very hard to self-recover.

“I was a member of the team for roughly 15 years, around,” Iversen said. “The conditions out there, let me tell you, they get very hairy and very scary.”

04/26/98

On the day of, Travis said he remembers being inside watching an NBA game- Bulls and SuperSonics- while Davis was outside working on the car. The call came in and Davis responded as team leader.

“He’s going out on a surf rescue. He’s done this a million times. You take it for granted,” Travis said. “I was so focused on Michael Jordan playing Gary Payton. You can second guess everything. But you can’t go back and change it. Why wasn’t I outside helping him work on a car?”

The call was for a surfer in distress by the north jetty, Iversen said.

“He wasn’t able to get back to shore. I think it was his buddies that called,” Iversen said. “It was down by the jetty, which is the most dangerous part of the beach.”

The call came in pretty early in the day, Fitts said, around 9 or 10 a.m. Iversen was not yet a full member of the team that he’d end up serving with for years, but answered anyway.

“I was working patrol that day. I wasn’t yet a member of the team,” Iversen said. “(Davis) took me out with him because there was no one else to go out with him.”

Fundenberger also said he walked down, despite being in recovery from a surgery.

“I couldn’t not go down to the scene and watch the team effect the rescue. I walked down to the beach with the crutches,” Fundenberger said. “They sent the Sea-Doo out with two guys to rescue this surfer who couldn’t get back in.”

Sgt. Paul Luck and Fitts launched with a Sea-Doo to get out to the surfer, while Davis coordinated from the beach. The Coast Guard had been notified as well, scrambling motor lifeboats from Westport and an MH-60 Jayhawk from Astoria.

“Paul and I launched. We saw the surfer lying on his board, totally wiped,” Fitts said. “We opted to say, we can tow him back in.”

The rescue starts to fall apart at this point, as a line is sucked into the Sea-Doo’s impeller and fouls the prop, knocking out the small watercraft. Fitts and Luck, along with the surfer, are now at the mercy of the currents.

“The rescue boat got disabled and that’s where the story begins,” Iversen said.

Watching from the beach as he ran the call, Davis made the decision to launch with Iversen in the RHIB, handing off control to Fundenberger.

“Davis was running the call. He said, I’m going to have to go out there to be with Chris,” Fundenberger said. “I took over running the scene.”

The outboard motor of the RHIB malfunctioned as Davis and Iversen headed out, adding more issues to a rescue that was spiraling hard. Investigating the aftermath of the incident indicated a likelihood that water had contaminated the fuel, Fundenberger said.

“I’m watching Chris and Jim basically monitoring us. Suddenly I can see them going upside down,” Fitts said. “This is not a good situation.”

Heavy surf hit the boat as Davis attempted corrective action, flipping the RHIB and putting them both in the water.

“The motor on the boat stopped for some reason. Lt. Davis was pulling on it and pulling on it,” Iversen said. “We got flipped.”

There were now four members of the team and the surfer in the water with no working watercraft. The cold water and heavy surf of the Pacific was taking its toll, Iversen said.

“It was a really rough day that day, as far as wave action,” Iversen said. “We got sucked under, tossed around, separated from each other.”

The situation had gone very bad very fast, Fundenberger said, as the rescuers were no longer under power, all of them too shallow for the Coast Guard motor lifeboats to effect rescues but too far out for other assistance.

“Now we had all our team and two watercraft circulating out there in that current,” Fundenberger said. “The helo got out there and started plucking people out of the water and taking them to the beach.”

Iversen, separated from Davis, watched them pull Davis out of the water.

“The helicopter got here. They sent a harness down to Lt. Davis and pulled him up into the helicopter,” Iversen said. “I knew he was struggling. When I saw him in the harness, I saw that he was limp and I was like ‘oh, wow, he’s in bad shape.’”

Davis’ condition is now critical, Fundenberger said.

“About halfway up, we get the call from the helo that they were going to make an emergency landing,” Fundenberger said. “They were almost losing him. Apparently he went unconscious about halfway up.”

Iversen said he was deeply scared at this point of how out-of-control the situation had gotten.

“I was scared to death. It was my first rescue and things were not going as they should be going,” Iversen said. “I was beyond scared. I was accepting my demise. I knew this was it. I knew this was it and I came to accept it.”

OSPD and OSFD are now fully engaged at this point in the rescue, Fundenberger said.

“The scramble began because we had all of our ambulances at the cul de sac,” Fundenberger said. “He was pulseless, breathless at this point.”

Emergency personnel attempted CPR on Davis at this point, Iversen said.

“The rest of the crew responded as quickly to the call with advanced life care,” Fundenberger. “They got him into the ambulance and headed into the hospital.”

Davis was medevac’d to Grays Harbor Community Hospital as word of the dire situation started to make its way around town.

Tragedy

The speed with which it all fell apart was something commented on by multiple members of the team.

“It just went south really quick,” Fitts said. “It’s went from ‘we should be on shore in a couple of minutes’ to, ‘why is he being airlifted?’”

Iversen said he drifted out far enough that the Coast Guard motor lifeboats were able to get him out of the water. Meanwhile, Travis said that he went to check on the rescue after it seemed like it was taking a long time.

“After what seemed like hours and he hadn’t returned, mom was worried,” Travis said. “I drove down to the north jetty to take a look.”

Not finding Davis’ car there, Travis said he ran into a friend, who told him that there was trouble, and that Travis needed to get to the police station. An officer there told him “You just getting down here finding out about this? You need to get down to the hospital.”

“We got to the hospital and we were told he passed,” Travis said. “That he had drowned, was the information we were initially provided. That was at the hospital.”

It fell to Travis to pass the news to other siblings out of state.

“(I) just remember calling her and telling her dad was gone,” Travis said. “She said, what do you mean he’s gone. I said, he’s gone. He’s not with us anymore.”

Davis never regained consciousness after being hoisted, Fundenberger said.

“They never were able to revive him,” Fundenberger said. “By the time we got back to the station, we knew he was dead.”

The other members of the team were debriefed before making their way as fast as possible to the hospital, Fitts said.

“I keep thinking that maybe something had gone a different direction that might not have happened,” Fitts said. “I’m not a pathologist. I’m not a coroner. Maybe that’s just wishful thinking.”

An honored legacy

The Ocean Shores Police Department is not a large one, and the death hit them hard, Iversen said. It was the department’s first on-duty death. Chief Mike Wilson was hit especially hard, Iversen said.

“We were devastated. It’s a small department, like a family. Our chief at the time, he and Davis were very close. The chief retired not long after that,” Iversen said. “It was tough for me. I had only been a full time officer for a year at that time. I had to come to work the next day and handle patrol calls.”

The town turned out, filling the Ocean Shores Convention Center with its largest crowd to date at that point. Law enforcement personnel came from across the country and as far as Canada to pay homage to Davis. Police from around the region turned out in full dress, leading a procession with the traditional riderless horse, boots reversed in the stirrups, through the town.

“Attitudewise, we understood it was a tragedy. We dealt with requirements to keep that service going. The victims didn’t go away,” Fundenberger said. “We honored him and kept going.”

The department and the town honored him both, and helped the family get through it, Travis said. The football field was renamed after Davis, who had served as assistant coach, and various plaques and memorials were dedicated to him across the town, and elsewhere, with Davis’ name added to memorials in Olympia and Washington D.C.

“Ocean Shores PD is and always has been phenomenal with us,” Travis said. “They’d stop by, check in. They were really supportive of my mom.”

The surf team was disbanded several years ago due to budget constraints, but the call to respond still lives, Iversen said.

“When you’re driving on the beach and some little girl says, ‘can you save my dad,’ what are you going to do?” Iversen said.

It’s a thread that connects all the members of the surf rescue team: the willingness to go and attempt to wrest a life in peril back from the merciless ocean.

“We want to make a difference. It’s hard to say no. Even when they shut us down, I’m going to go in the water,” Fitts said. “There was no hesitation on our part to put ourselves in harms way. That’s the name of the job.”

Saving lives made the job worth it, Fundenberger said.

“That’s the sort of thing that really made it worthwhile. Really being able to affect life longevity,” Fundenberger said. “That’s the attitude of the whole team. That’s why we were there. Towing people back to the beach, where they were safe.”

Contact Senior Reporter Michael S. Lockett at 757-621-1197 or mlockett@thedailyworld.com.