On Friday morning, in a classroom flanking the administrative office at Aberdeen High School, Cosette Terry-itewaste wrote five Quinault language phrases on a white board in black dry erase marker. “Nuɡwitu” she greeted a handful of students as they entered the room.

In what was their second lesson on the Quinault language, the students followed Terry-itewaste as she acted out and uttered a series of phrases — happy, sleepy, hungry — and challenged students to see who could most quickly match spoken phrase with images on paper cards.

For students in Native Education Programs at Aberdeen and Hoquiam school districts, Friday was the second lesson in Quinault language, part of a larger effort to revitalize the dialect and prevent it from vanishing.

“We just started going to the schools,” said Terry-itewaste, lead teacher and language developer with the Quinault Language Department. “We were focusing mostly on families, because that’s where you learn language.”

Since forming in 2016, the tribe’s language department, which consists of Terry-itewaste, two other language teachers and a media specialist, has offered online and in-person Quinault language classes to families and young children, and last fall started teaching at the Queets-Clearwater school in Forks. Now, the department aims not only to reach the many Quinault students in other Grays Harbor school districts, but have those students permeate it back into family life.

Sandy Ruiz, coordinator of the Native Education Program at Hoquiam School District, said she was “very, very excited” when Terry-itewaste asked about coming to the district to teach Quinault language.

The classes are only being taught to students in the Native Education Program, which requires Native heritage to participate. Ruiz said she hopes to expand the language to other classrooms, although that would be up to the tribe.

“I think its super imperative that our kids have access to it,” Ruiz said. “Especially with tribal languages being as endangered as they are. Not all tribes have access to a full dictionary.”

For decades in the late-19th and 20th centuries, Native American students were involuntarily enrolled in boarding schools operated by the federal government and churches. They were harshly punished if they spoke traditional languages, and many lost the ability to speak traditional languages fluently.

In 1969, Ruth Modrow authored the Quinault Dictionary and Quinault Conversational Text, which provided a framework for the language to be taught at Taholah schools in the following decades, which maintained awareness of the language. However, as Terry-itewaste, who earned a doctoral degree in linguistics from the University of Arizona in 2016, wrote in a dissertation, learning the language proved difficult.

“The Quinault language is considered dormant, since there are no fluent speakers yet,” she wrote. “Although traditional cultural lessons and isolated Quinault words were taught in the Taholah School, revitalization required a new approach,” she wrote.

In 2006 the federal Esther Martinez Native American Languages Preservation Act devoted federal funding to restoring Native languages. The Quinault Indian Nation kickstarted the revitalization effort in 2008 by ratifying the tribe’s language teacher certification process with the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction. The state’s First People’s Language/Culture certification opened the door for more Quinault elders to become officially certified as language teachers and for students to receive credit for Native language classes.

Terry-itewaste’s doctoral degree research, which was supported by the Quinault Indian Nation’s Graduate Fellowship, focused specifically on achieving Quinault language revitalization through classroom lessons. She writes about a linguistics theory called Total Physical Response, in which learning is based on “physical responses to commands include gesturing, walking and repeating the phrases they are learning.”

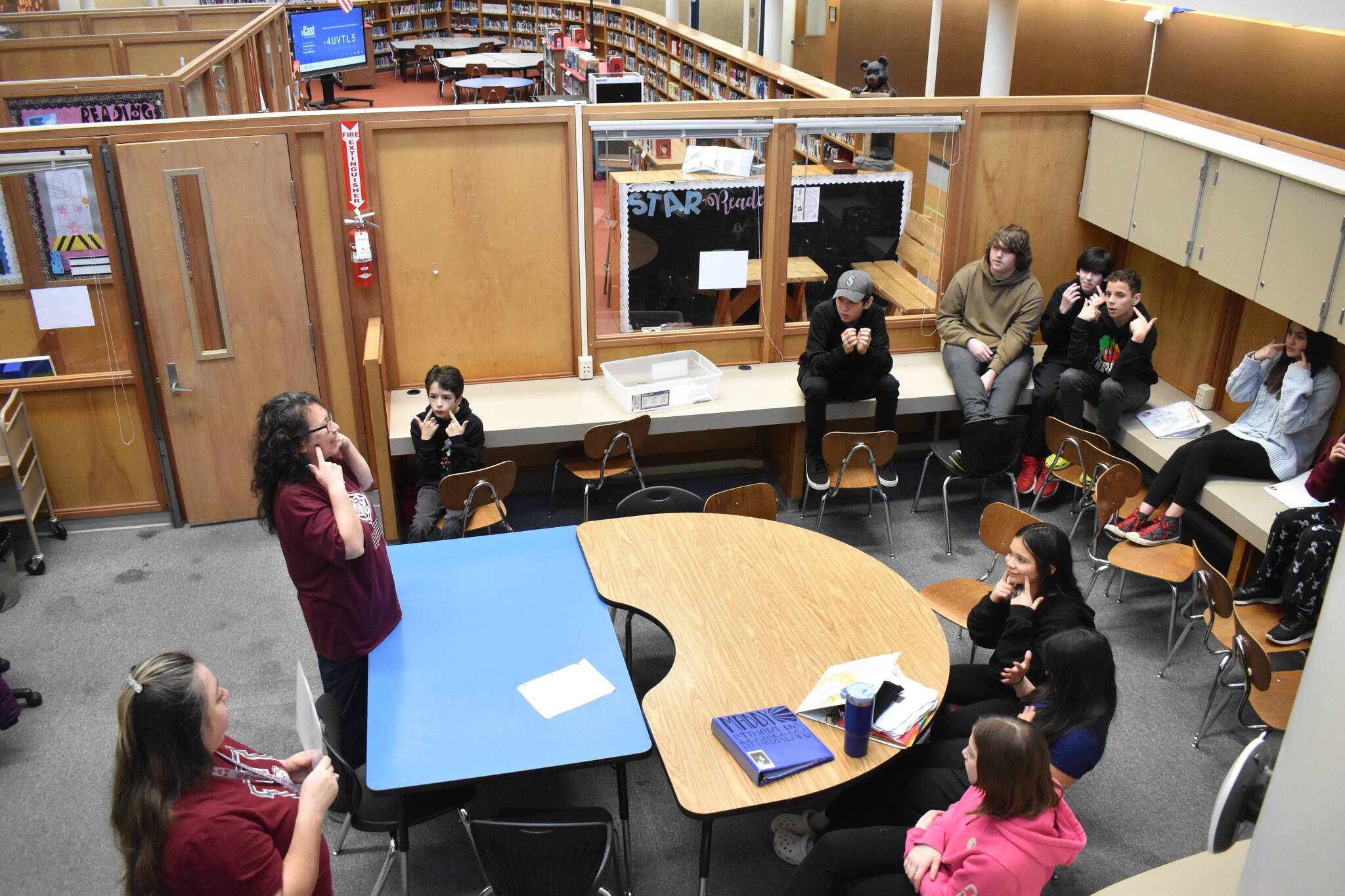

At Hoquiam Middle School, students raced around a library classroom to identify pictures that matched verbal commands from Terry-itewaste. Instead of focusing on the written word, students made audio recordings of their teacher reciting Quinault phrases.

“There’s so many different ways to learn something, and I think she kind of hits all those points,” said Ellie Long, a senior in Aberdeen’s Native Education Program. “That’s really helpful because I learn through pictures and repeating. Having those images or those movements that you get to do with it kind of helps.”

Repeating phrases multiple times was the key for Aberdeen High School Student Caleb McGuire, who is Quinault and Chippewa.

“After the second time I heard it, I was pretty sure I got it,” he said after Friday’s lesson.

Other students have used the phrases outside the classroom. Julia Dooley, a sixth-grader in the Native Education Program at Hoquiam Middle School, prefers to use the phrase “x̣əɫnɑʔɑni” — which means “later” — to bid adieu, as opposed to the more final “ox̣nɑni,” which means “goodbye.”

“Goodbye means ‘goodbye forever,’” Dooley said.

Preston Williams, a sophomore in the Aberdeen Native Education Program, said he was able to use Quinault phrases for farewell in conversation at the YMCA, and nicknamed his mother’s orange Dodge Dart after the Quinault phrase for the color.

Long, who is Quinault and Siletz, said she previously had little exposure to many Quinault traditions, including the language.

“It’s kind of like I’m getting to know those ancestors I haven’t met yet,” she said.

While Aberdeen and Hoquiam students are just beginning their studies, some participants in the language department’s family classes are now able to speak conversationally with each other and instructors, Terry-itewaste said.

But she said scholars would still consider the Quinault language endangered.

“I’m hopeful for it,” she said.

Contact reporter Clayton Franke at 406-552-3917 or clayton.franke@thedailyworld.com.