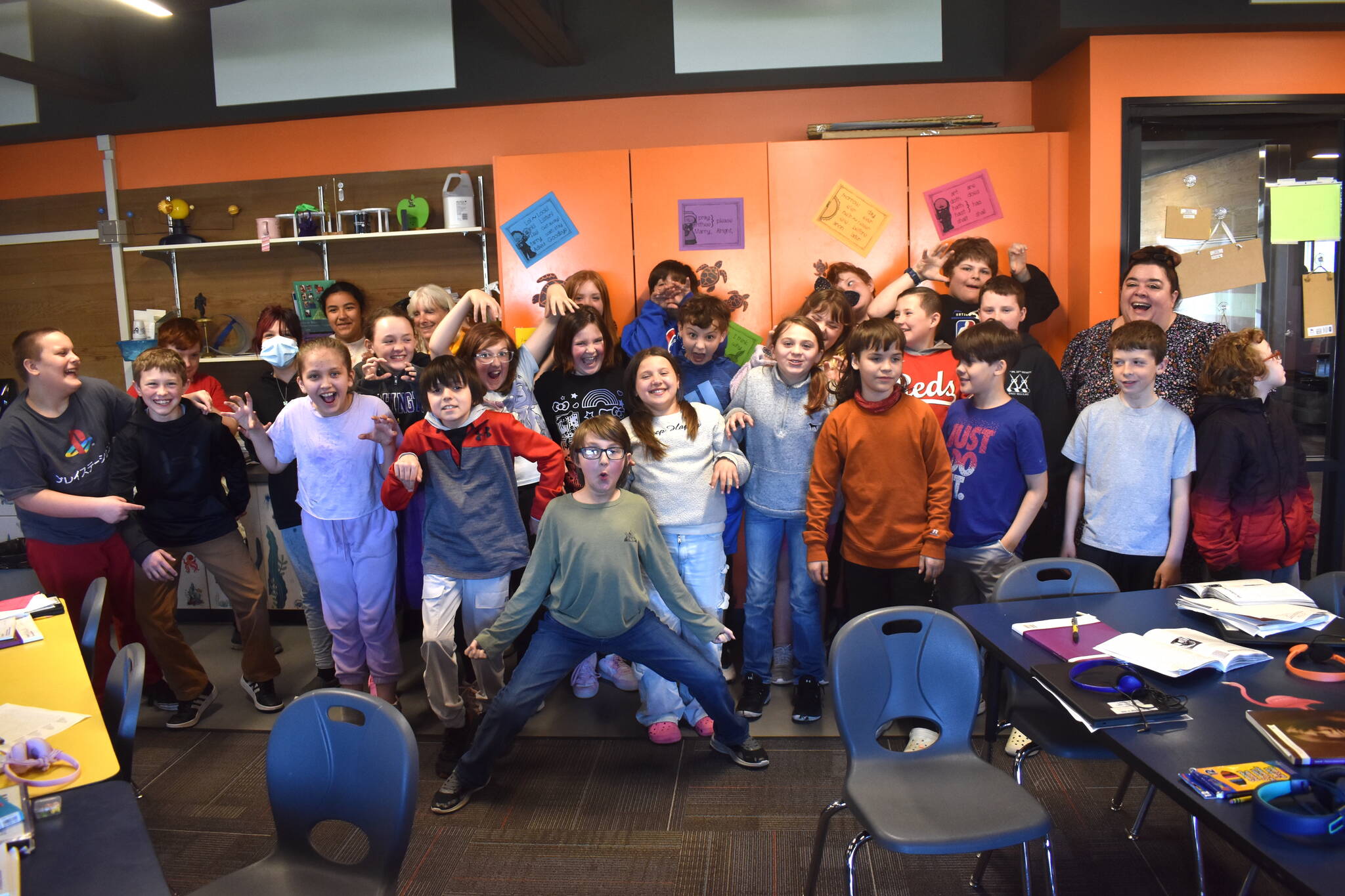

For the third year in a row, a class of fifth graders in Hoquiam has secured legal protections for Sasquatch.

Thanks to the lobbying efforts of Andrea Andrews’ fifth-grade class at Lincoln Elementary, a refuge for the big hairy ape now spans across most of the Olympic Peninsula, with only Jefferson County left to follow suit, and a proposition there is already in the works.

In April, Mason County became the third local jurisdiction in the last three years to be persuaded by a letter from Andrews’ class convincing the commission to adopt county-wide Bigfoot protections. Last year’s class secured protections in Clallam County, while the 2022 class passed a resolution in Grays Harbor County.

“It was hard to write it,” said student Waylen Voynow. “At the end it was very relieving that we got it passed, because you’re doing something for a species or animal that might exist. It just sounds really important.”

The effort is the result of Andrews’ yearly lesson titled “Saving Sasquatch.” Each Spring, Andrews guides her class through research and debate over for and against the existence of Bigfoot. The 10- and 11-year-olds then write up a persuasive essay to turn in, followed by a collaborative letter sent to county commissioners.

Andrews intends for the lesson to be an exercise in critical thinking and civic action, urging students to think about implications of potential Bigfoot protections.

“They get to see all aspects and make up their own minds on whether they think Bigfoot is real or not,” she said.

While last year’s class was overwhelmingly in favor of pursuing protections for the hairy cryptid, this year’s class was slightly more divided, with two-thirds voting in favor of saving Sasquatch. In its letter to Mason County’s legislative body, that group told commissioners there had been 24 reported sitings within the county and “at least one of those sitings are real.”

“What if Bigfoot is harmless?” the class queried commissioners. “Bigfoot could just be another animal wanting to survive like everyone else. Sure, if we attack it, it would probably attack back, but that’s just self-defense in general. Any animal would do that, even a bunny!”

Student Colin Martin, who argued in favor of the Sasquatch saving effort, was convinced by hearing recordings of Bigfoot calls she found through online research. Another proponent, Xander Hicks, said the evidence was compounded by his own apparent encounter in Cosmopolis, where he heard a howl resembling “a predator sound, like a wolf, fox, bear mixed.”

For the first time since the launch of Andrews’ Sasquatch lesson, students could draw from expert advice: Dr. Jeffrey Meldrum, a professor of anthropology and anatomy at Idaho State University and prominent Sasquatch researcher. Andrews reached out to Meldrum about the class project, and the professor agreed to present to the class virtually.

Student Mason Warren, said he learned from Meldrum that Bigfoot likely has a very low population density, which was a cause for protections.

Another student said protections were needed to prevent hunting, because if a hunter were to shoot the giant hairy ape, the beast would probably engage the human in a fight, and “the Bigfoot would totally win.”

On the contrary, Harrison Dejka, who did not support Bigfoot protections, argued the new rules would outlaw hunting or capture, which would therefore diminish any chance of proving its existence.

But the main argument for the dissenters, nicknamed the “time-savers,” was that the effort to protect a mythic animal was futile.

“We think that you guys are wasting your time trying to get laws protecting something that’s not real,” said a letter the subset of the class wrote to the Sasquatch savers. “There is no proof that there is actually a Bigfoot out there.”

“Most calls either sound fake or like another animal,” they added.

“I don’t think Bigfoot is real, only because it looks like a bear, to be honest,” said student Lucas Mousley, who joined the time-savers group. “With all that fur, and the foot, it looks totally like a bear.”

After the fifth-graders presented their findings to Mason County, the county passed a resolution modeled after other Bigfoot legislation. It created a “Sasquatch protection and refuge area,” stating that “legend, sightings, purported recent findings, investigation and recognition by various counties support the notion that Sasquatch (also known as Bigfoot, Yeti or Giant Hairy Ape) may exist.” Should the beast exist, the county argues, then it is not flourishing, given the scarcity of sightings, and should be protected.

In addition to three counties on the Olympic Peninsula, two others already have protections: Skamania, which adopted an ordinance protecting Sasquatch in 1969; and Whatcom, which did the same in 1991. A 2018 bill in the Washington state Legislature proposed to designate Sasquatch as the official state cryptid but was never passed.

But according to Andrews, Mason County Commissioners forwarded the class letter to the state Legislature with hopes it would prompt larger action.

“If they do that, we’re going to be out of the county business,” Andrews said. “I guess these classes are going to have to go state to state.”

Contact reporter Clayton Franke at 406-552-3917 or clayton.franke@thedailyworld.com.