By Corbie Hill

The News & Observer

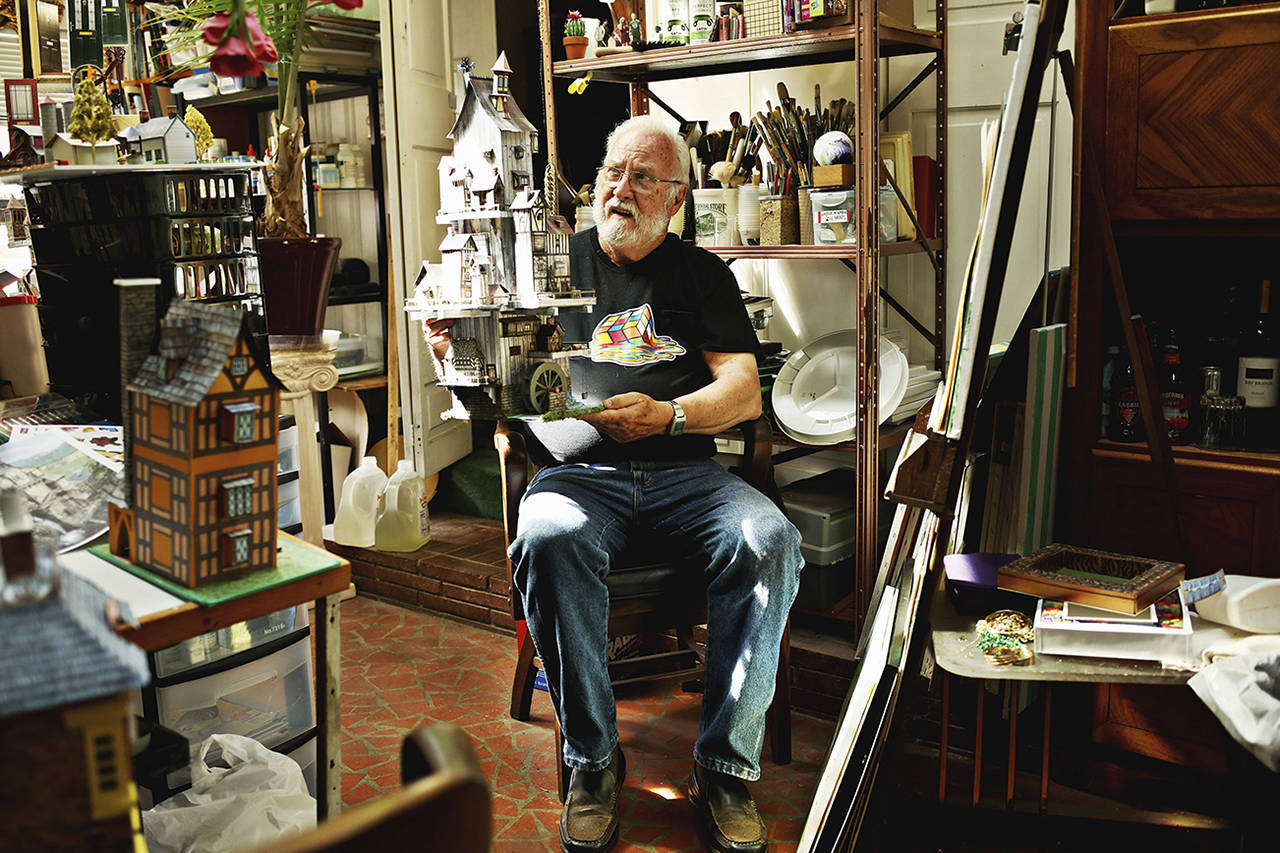

RALEIGH, N.C. — There’s another world in the greenhouse-like back room of Jim Kellison’s house.

Along one wall, seagulls fly. He likes to mix two- and three-dimensional art, so the waves are painted flat onto a canvas, while the gulls seem to skim above it. Near the door to the front of the house is a diminutive N-scale train layout whose tracks pass by a basketball game, a wedding, a funeral and a bus station — all elements of a well-imagined town.

Kellison has built dollhouses, complete with working lights and families in still life; in one, a party is about to commence. He has built castles, lighthouses and complete towns, all out of paper. He has built an entire fishing village, and a house with a working elevator.

These lightweight models fill the shelves of the back addition of Kellison’s little house in Raleigh.

“I get up about 7, 8 o’clock and I’m doing papercraft until it gets dark, until I have to turn on the lights,” Kellison says. “Then I quit.”

Yet he’s never publicly exhibited the art he’s dedicated himself to in the 16 or so years he’s been retired. For all that time, he has quietly and contentedly filled the back of his house with elaborate models and cityscapes.

But this Saturday, during a community garden workday, Kellison will display his paper models in the parking lot of the neighboring Wesley Memorial United Methodist Church.

“I wanted to exhibit my papercraft somehow, so I was just going to put tables out in my driveway and in the church lot to let people stop by and see,” he says in his understated, easy way. He’s quiet and calm and — if the delicate paper models throughout his house are any indication — patient and gentle as well. He doesn’t seem to speak much, either, but doesn’t need to. He simply doesn’t mind silence.

At first, Kellison made his paper models from punch-out patterns he downloaded from the internet. These include castles, cathedrals, “Star Wars” characters and a scale model of a space shuttle resting on a massive crawler-transporter.

After completing numerous models from these patterns, he decided to create his own. He does this by printing textures — brick or corrugated roof, for example — directly to card stock. Then he creates.

“It’s like solving a puzzle,” he says. “Then you’re surprised when you’ve got this finished little building with doors and windows.”

On this day, Kellison is working on a fantasy mill, its medievalesque character and unlikely proportions placing it in a fictional sword-and-sorcery world. There are differences between the picture from which he’s basing the model and the model itself. Today, for instance, he’s thinking about where he wants its shacks and outbuildings to go.

Kellison also builds traditional — that is, non-paper — dollhouses. One of these sits in the unused nursery at Wesley Memorial next door, waiting to be taken downtown.

“The dollhouse, which is right over here right now, is going to be auctioned at Marbles (Kids Museum) to raise money for us,” says Lucinda MacKethan, manager of the church’s Planting on Whitaker community garden. Kellison doesn’t attend the church, but he’s been a big supporter of its community garden and a good friend to many parishioners. He has bought fruit trees and bushes and helped plant them, and he has put in many hours working in the church’s garden.

Like his paper models, gardening is something he does to pass the time.

“It’s just sitting around,” Kellison says with a chuckle.