By Sean D. Hamill

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

PITTSBURGH — She was just another beagle that Lawrence Vernetti had scheduled to take part in another drug experiment.

But by the time he met this particular pooch in 1994, he had already assigned hundreds more beagles — the dog of choice for drug research, thanks to their small size and docile nature — to be experimented on in his role as study director at Abbott Laboratories in Chicago.

“I don’t know why” this one caught his attention, he said recently during an interview in his office at the University of Pittsburgh, where he is associate professor of computational and systems biology. “But when you do work with them, you can develop a connection. I did with her, and after that I stopped wanting to work with animals.”

Plagued by his emotional tie to the unnamed beagle but wanting to continue to work at Abbott, he proposed to his supervisor that they begin an in vitro research lab that would use cells or bacteria, instead of animals, to test drugs.

The company agreed. After a couple of years establishing the lab, Vernetti entered a nascent field that now, nearly a quarter-century later, is building support across research and industry for reasons that go beyond the compassion of avoiding experimentation on animals.

“There has been a sea change in attitude,” said Vernetti, who recently won a $50,000 grant from the Beagle Freedom Project to continue his research into developing a human liver model that could help companies avoid using animals for experimentation.

Drug companies and others who have used animals for pre-human testing of drugs and other chemicals have known for a long time that results with animals were a poor predictor of their effect on humans. One study found that animal testing is only reliable 70 percent of the time in determining the basics of whether a drug or chemicals would be toxic to humans.

But finding a way to replace animal testing seemed daunting, despite the work of Vernetti and others on using cells.

When he started the in vitro lab at Abbott, Vernetti’s experiments were basic: They would just put the proposed drugs on cells and wait to see if they died. But over the past decade, the field has begun developing human “microphysiological systems.”

The field is sometimes referred to as “organ-on-a-chip,” or the larger goal of “human-on-a-chip.”

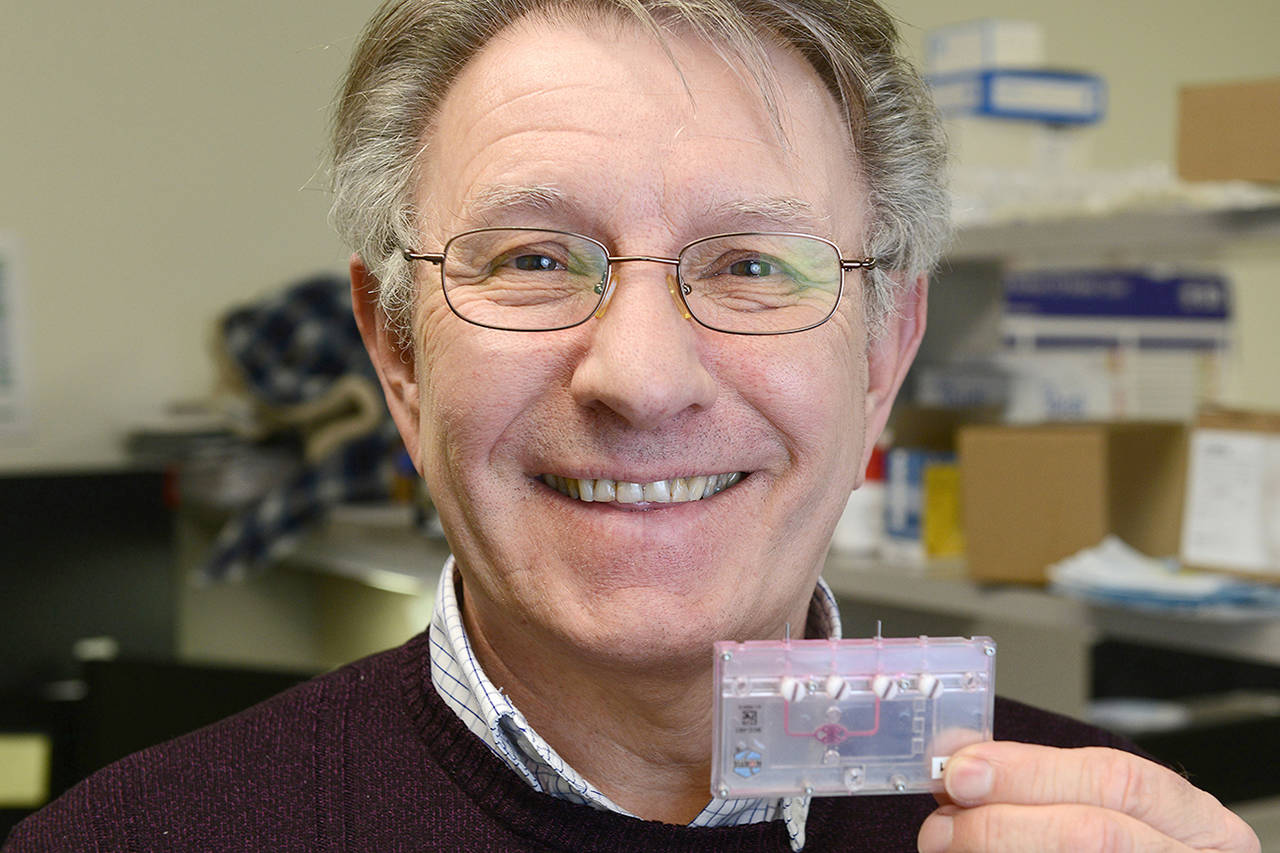

It grabbed those catchy phrases because, rather than any kind of scale model of an organ, these devices are created with a couple of cells from a specific organ that are placed into a plastic-and-glass “chip” no bigger than a business card.

The theory is the cells can show the reaction to drugs or chemicals — which are pumped into the chip — in the same way a working organ in an animal or human would.

Researchers believe they may also prove to be a big step in the field of precision medicine that will make treatment for individual patients much more effective. And the field would have the benefit of reducing the high cost of using animals for research, while eliminating the ethical dilemma that many, like Vernetti, have dealt with using animals.

The human-on-a-chip idea is that after the 10 major organs — and other parts of the body, like the eyes or the central nervous system — are replicated in this way, they can be connected and a chemical or drug could be run through all of them to see how they would impact an entire human body.

Vernetti, who is also director of early drug safety for Pitt’s Drug Discovery Institute, has been working for six years creating a liver-on-a-chip. It uses human liver cells taken from medical procedures involving a living patient’s liver, from bodies donated to science, or from livers originally intended for organ donation but were not used — all with approval from the patient or deceased.

Despite a recent journal article that showed the potential of linking his liver model with other organs and systems, Vernetti said: “We’re not quite at the level where we can get an entire human body on a chip.”

His most recent grant came from the Beagle Freedom Project, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit that since 2010 has pushed for the elimination of animal testing and provides homes to dogs — not just beagles — and other animals previously used in research.

The project chose Vernetti’s work for one of four $50,000 grants it made this year, all funded by the Microsoft Foundation.

“All four grants share something in common in that they aspire to reduce using animals in research,” said Jeremy Beckham, a research specialist at the project.

Vernetti is using his grant funding to help pay for research into producing the first workable liver-on-a-chip with a more realistic bile duct component.

Bile is a fluid produced by the liver through the bile duct. It aids in the digestion of lipids in the small intestine, an important part of the digestion process.

Other researchers have developed working liver models, but “nobody has been able to figure out how to make one with a realistic bile duct,” Vernetti said.

After refining the bile duct portion of his liver-on-a-chip, his next goal is to connect the working liver and bile duct chip with a colleague’s intestine-on-a-chip. Mark Donowitz, a researcher at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, is developing that chip using human intestinal stem cells.

Vernetti wants to connect their two projects to analyze how the human body removes toxins, because he says the combination of the liver and its bile duct with the intestine “is the first line of defense for that.”

Donowitz has only been working in the microphysiology field for five years, but is excited by what his early studies have shown.

“It has the potential to give new insights into physiology and drug development and other areas,” he said. “But we have to prove it can work first.”

One of the big hurdles to elimination of animal testing is that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires animal testing for drugs before human trials can begin. If it’s possible, it will take years to prove to the FDA and others that the organ-on-a-chip technology can adequately replace animal testing.

But Vernetti, 64, likes what he has seen so far of the results. “I do believe that through this kind of work we can eliminate animal testing, even if my career may be over before it happens.”