By Darcel Rockett

Chicago Tribune

Matt Webb was 5 years old when he became aware of his gender identity and sexual orientation.

The 33-year-old native of McMinnville, Tennessee, said he was in karate class when he realized he was different from his brothers.

“I didn’t know what to do, I didn’t know what was happening, and I remember being very scared and vulnerable,” he said. “I couldn’t tell anybody and ask, ‘What’s this mean?’”

Three years ago, when Webb, a graphic designer and illustrator, was holding his newborn nephew, he again felt paralyzed with fear.

“I thought, ‘Oh, no. … I came from a small, conservative town in Tennessee. What if he grows up here (in Tennessee), and what if he’s gay? What if he’s bi? What if he identifies as LGBTQ? What will happen to him?’” Webb said. “I thought about that, and I wished there was some way I could teach the people around him … something that my nephew could grow up reading and learning. I mulled it over and thought, ‘I’m going to create a book.’”

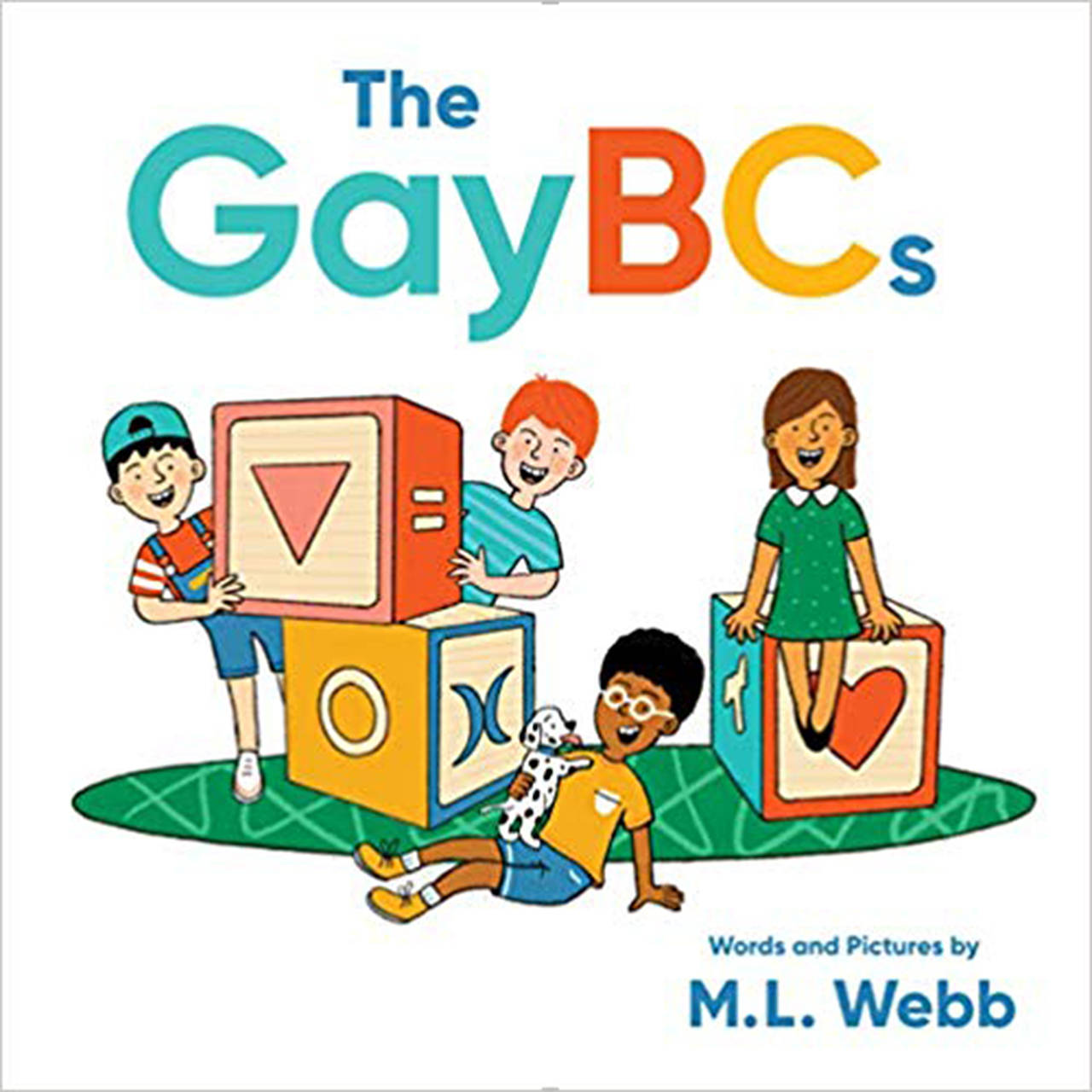

In “The GayBCs,” released this month by Quirk Books, the letters that make up our alphabet are paired with terms like:

C is for Coming Out: “You’re ready to share what you feel deep inside; it’s okay to be scared.”

I is for Intersex: “Some are born with the parts of both a boy and a girl; bodies are works of art!”

P is for Pan: “You connect with a vibe. No matter the gender, it’s about what’s inside.

The book, a first for Webb, teaches LGBTQ+ vocabulary with poems and illustrations in an attempt to help readers ages 4-8 begin to have a dialogue about identity with their loved ones.

“It’s the kind of book that I wish I had as a child,” he said. “When I was 5 years old, I knew that I felt differently than the people around me, but I didn’t have the words.

“I just thought of other little 5-year-olds who are just kind of starting to notice things and thought what would be the best thing for them that would be something that is inviting, but also something that they could use their own words to communicate.

“You think about school and how you’re taught the same lessons year after year, and you think it really doesn’t matter, but at the same time, it’s reinforcing. The book is normalizing how people identify and normalizing how allies see themselves and their friends.”

Lindsay Amer, the creative mind behind the YouTube channel Queer Kid Stuff, which provides educational LGBTQ+ videos for all ages, thinks the book is necessary for families to have in their libraries. The channel has over 17,000 subscribers who have been tuning in to learn things about the LGBTQ+ community for almost four years. Amer, a Northwestern University graduate, said instructional/educational books like Webb’s are definitely needed.

“I think over the last five years or so, there’s definitely been an increase in LGBTQ+ children’s books, but it’s still not an incredibly robust space,” Amer said. “I think it’s important for us to be making content that fills out a genre and fills out options for people. You want to make sure that you’re getting books that are written by authors who come from a diversity of backgrounds and we’re telling lots of different stories. So we’re not just getting the trans story, we’re also getting characters that are nonbinary and who have different family structures. And it’s important to make sure those books reflect students in the classrooms.”

Webb’s addition to the LGBTQ+ lexicon is also being commended by the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network, a nonprofit that focuses on LGBTQ advocacy within K-12 school systems. According to Becca Mui, GLSEN’s education manager, helping young people see themselves and understand the world around them and how diverse it really is benefits all students.

“Young people begin to develop identity-based markers and categories at 2 years old, so it’s never too early to introduce identity or diversity to young people, particularly in the structure of picture books,” she said. “The one thing that I like about this book — picture and alphabet books — is their common structure for young people. Fitting information within that common familiar structure can help introduce a new topic in a familiar way.”

Amer says books like Webb’s would have helped her when she was younger.

“When I think back when I was a kid, I had a very strong understanding of pronouns, but I didn’t necessarily have the language to express it,” Amer said. “I was an androgynous kid, and people would think I was a boy, and it was hurtful because I knew I wasn’t being perceived in a way that I wanted to be perceived. I didn’t have the language to express myself and say, ‘No, that’s not my pronoun.’ I didn’t have an understanding of what gender even was, but I knew what it was intrinsically. So it’s important to give kids that vocabulary to empower them to say, ‘Hey, you’re wrong; this is my gender.’”