By Samantha Masunaga

Los Angeles Times

The U.S. naval fleet of the future may one day include submarines without a sailor from bow to stern that prowl the depths of the ocean, navigating mine-infested waters to gather intelligence or even clandestinely drop explosives.

The military views autonomous vehicles as a way to accomplish missions deemed too risky, mundane or expensive for human crews. While aerial drones have largely been tasked with these types of duties for more than a decade, the Navy is now increasingly funding robotic ships and undersea drones to complement the work done by its crewed vessels.

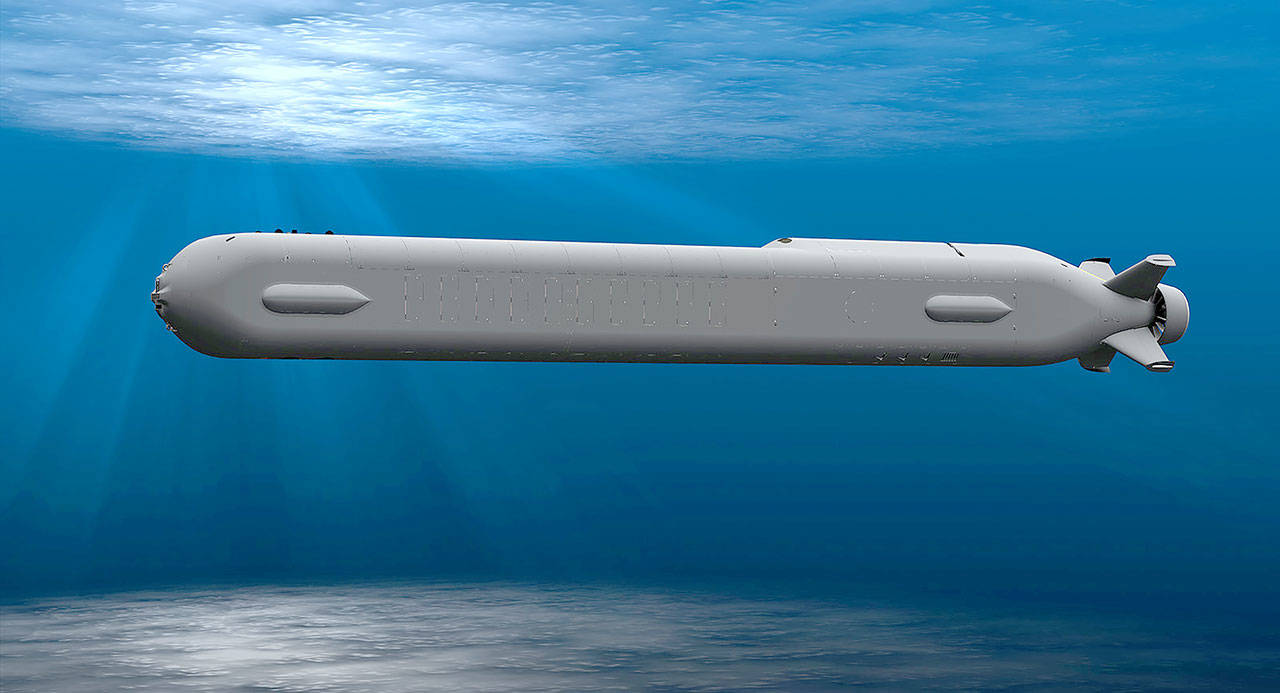

Last month, Boeing Co. beat out rival Lockheed Martin Corp. for a $46.7-million Navy contract modification to build an Orca undersea drone. Boeing had previously won a contract to build four of the Orca drones, bringing the total contract value for the five to $274.4 million. A large chunk of work will be done at the aerospace giant’s Huntington Beach facility, and the drones are expected to be completed by 2022.

Neither Boeing nor the Navy have disclosed the size of the robot submarines, but Boeing has previously developed and tested a 51-foot-long underwater drone prototype called the Echo Voyager.

Analysts say the contract, along with the Navy’s new fiscal year 2020 funding request for further development of uncrewed surface vessels and undersea drones, indicates a new level of commitment to autonomous sea operations.

“What it shows is that the Navy is willing to start putting some real money behind the acquisition of unmanned undersea vehicles,” said Bryan Clark, senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments think tank in Washington, D.C. “This is the first time the Navy has put significant money down on UUV (unmanned underwater vehicles) that have a military, war-fighting capability.”

Analysts say undersea drones could be used for missions once conducted by crewed submarines, while the lack of a crew gives the drones an advantage in conducting “persistent surveillance for activities that might take place in an area where there is concern about underwater mines,” said Margaret E. Kosal, associate professor in the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Future missions might also include deploying military payloads or weapons into a contested area, Clark said. But developing undersea drones comes with a host of technical challenges not experienced by aerial counterparts.

For one, water is a much thicker medium, which makes real-time communication much more difficult than sending transmissions through air, said Rosa Zheng, a professor in the department of electrical and computer engineering at Lehigh University.

Undersea drones can use a few different methods of communication, such as acoustics, but must be willing to trade off a slower data rate, shorter transmission distance, or both, she said.

As a result, the drones must be endowed with a greater level of autonomy than aerial drones, said Scott Savitz, a senior engineer at the Rand Corp. think tank. Unlike an aerial drone, which can access satellite communications to gain its bearings and show what it sees in real time to a human operator thousands of miles away, an underwater drone loses access to the electromagnetic spectrum once it is below the waterline, he said.

That means the drone would have to handle changing weather conditions or avoid obstacles underwater without human assistance. It would also need to resurface to send faster transmissions and gain access to GPS.

“There’s a need to develop greater autonomy for UUVs than there was for UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles) and … to have enough trust in the system, which can only be achieved through testing, evaluation, usage and so on,” Savitz said.

Boeing has worked on some of these issues with its Echo Voyager underwater drone prototype.

The 51-foot-long, yellow-and-gray submarine-shaped drone has completed more than 2,500 hours of ocean testing, including two sea trials. During the first tests in 2017, Echo Voyager operated for about three months off the coast of Southern California while monitored by a crewed chase boat.

The drone is powered by a hybrid electric-battery/marine-diesel system. A generator kicks in when the battery runs low, and the drone will periodically resurface to snorkel depth to raise a mast that provides air to run the diesel engines, which recharge the batteries. During the first sea trials, Boeing tested the drone’s ability to surface, recharge and submerge, as well as its control in currents and waves.

The drone is designed to be programmable so it can launch from shore, complete its mission and then return when it’s done, said Deborah VanNierop, a Boeing spokeswoman.

Echo Voyager is currently in its second round of sea trials, which began last year, VanNierop said. Testing and lessons learned from Echo Voyager have been incorporated into the Orca design to improve reliability and reduce risk, Boeing said. However, Van Nierop said the two vehicles will not be exactly the same.

Eventually, the Navy could pair these underwater drones with their uncrewed surface counterparts.

This year, the Navy’s 132-foot-long Sea Hunter autonomous surface vessel sailed from San Diego to Hawaii and back without crew aboard. The ship’s maker, Reston, Va.-based Leidos, said humans made “very short duration boardings” only to check electrical and propulsion systems.

These kinds of medium-size vessels could be used for sensing operations, to conduct electronic warfare and to support crewed aircraft carriers, Clark said. Larger autonomous surface vessels could even be used to deploy undersea drones.

“Just as it took some time to figure out how submarines would be interacting with the rest of the fleet, and their various roles … likewise, there’s going to be an evolutionary process with respect to deployment of UUVs for a wide range of missions,” Savitz said.