By Thomas Curwen

Los Angeles Times

Nearly $6 billion has been allocated. Clinical trials are entering a crucial third phase, and Operation Warp Speed is getting closer to the goal of delivering 300 million doses of a COVID-19 vaccine by January.

But when Americans line up for their immunizations, the vaccine they receive might not be what they expect. The popular notion of a vaccine — a shot in the arm that prevents diseases such as measles, polio or shingles for years or a lifetime — may not apply.

Under recently released federal guidelines, a COVID-19 vaccine can be authorized for use if it is safe and proves effective in as few as 50% of those who receive it. And “effective” doesn’t necessarily mean stopping people from getting sick from COVID-19. It means minimizing its most serious symptoms, experts say.

“We should anticipate the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine to be similar to the influenza vaccine,” said Dr. Kathleen Neuzil, director of the Center for Vaccine Development at the University of Maryland. “That vaccine may or may not keep people from being infected with the virus, but it does keep people out of the hospital and the ICU.”

Even with expectations scaled back, the development of a vaccine against a virus that no one knew about seven months ago is considered remarkable. One assessment calls it “the compression of six years of work into six months.”

Of the more than 150 vaccines in the works worldwide, Operation Warp Speed has identified 14 “promising candidates.” (A vaccine being developed by El Segundo-based ImmunityBio, headed by Times owner Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong, is among the 14. It has not yet been tested in humans.)

Of those 14, seven have been designated as front-runners, including three whose early clinical trial results have undergone independent evaluation.

The vaccine being developed by Moderna and the National Institutes of Health was deemed “promising” in an editorial published in the New England Journal of Medicine, and two studies in the Lancet delivered a similar message for vaccines being developed at Oxford University and by the Chinese company CanSino.

These vaccines have induced an immune response in people participating in early tests, but inducing an immune response does not always mean success in fighting a disease. For instance, scientists recently developed a vaccine for another respiratory virus that increased antibodies but failed its Phase 3 clinical trial.

While there is no way to predict what lies ahead, experts say, the first round of COVID-19 vaccines will likely not eliminate the need for other public health measures, such as masks and social distancing.

The minimum 50% efficacy recommendation spelled out in late June by the Food and Drug Administration would likely ease the burden on hospitals. And to whatever extent a COVID-19 vaccine prevents infection, it could reduce the spread of the virus and help to create pockets of immunity throughout the country, said Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of Baylor College of Medicine’s National School of Tropical Medicine.

“Ideally, you want an antiviral vaccine to do two things,” Hotez said. “First, reduce the likelihood you will get severely ill and go to the hospital, and two, prevent infection and therefore interrupt disease transmission.”

In this case, he added, “the bar does not seem that high.”

Developing a vaccine capable of inducing “sterilizing immunity” — that is, the ability to prevent the virus from causing an infection — takes time and research, which might not be possible as death tolls continue to rise and the recession grows deeper. Yet with so many companies on the hunt for that vaccine, there is hope one of them might actually achieve it.

Dr. Mark Feinberg, CEO of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, cites the success of the Ebola vaccine. Not only did it speed through its clinical trials —from starting Phase 1 to getting early Phase 3 results in 10 months —but it also was nearly 100% effective within 10 days of a single dose being administered.

That’s not likely to be the case now. “The challenge is that the novel coronavirus hasn’t been around long enough,” Feinberg said.

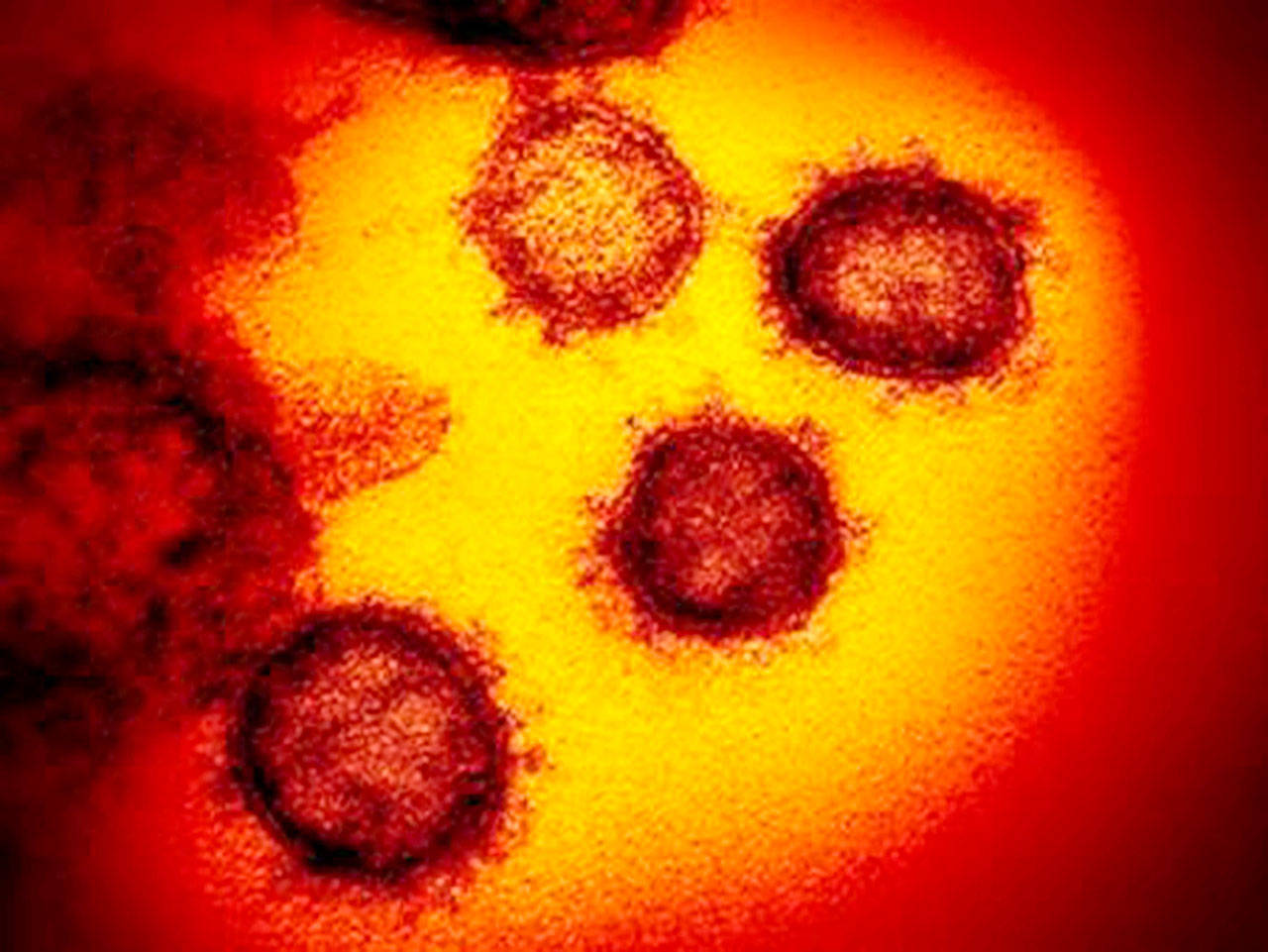

Scientists had studied other coronaviruses — SARS and MERS — and mapped the novel coronavirus’ genome not long after the first COVID-19 deaths were recorded. They identified the spike protein on the virus’ outer shell, which the virus uses to infiltrate the host cell and created a three-dimensional model of the virus to see how antibodies block infection by binding onto the spike protein.

Even so, scientists don’t yet know what immunity against the virus looks like. That information typically comes from studying the body’s natural response to disease. The number of T-cells and neutralizing antibodies that fight off an infection can become a blueprint for a vaccine.

But the novel coronavirus is not easily giving up those secrets.

Physicians have noted a wide range of immune responses to COVID-19, Feinberg said. Some patients produce high levels of neutralizing antibodies, while others produce only low levels.

“What’s interesting is that all have recovered, and we do not know how they did this,” said Feinberg, a former chief public health and science officer with the pharmaceutical giant Merck.

Scientists are also uncertain how long immunity — from a natural infection or a vaccine — lasts and whether a decline in antibodies in two to three months is cause for concern.

The third phase of clinical trials might answer some of these questions. Moderna is enrolling 30,000 people for its Phase 3 trial, which started Monday.

“If we get a vaccine that is 60% efficacious, we can use the information to identify what distinguishes people who are protected from those who are susceptible, ” Feinberg said. “Then we will know what the minimum target is for an immune response.”

But the absence of that information does not preclude the distribution of a vaccine. Many vaccines are effective even though scientists don’t know the amount of antibodies needed to prevent infection. A vaccine can even be effective if it doesn’t prevent infection.

The polio vaccine that Jonas Salk developed does not stop the poliovirus from infecting the gastro-intestinal tract, said Feinberg, but it stops the virus from traveling to the central nervous system where it causes the disease’s worst symptom, paralysis.

With so many questions still unanswered, the effectiveness of a COVID-19 vaccine may not be known until well after Americans have received their shots.

Among the recommendations in the FDA guidelines is a provision for emergency use authorization, allowing for the distribution of a vaccine if “the known and potential benefits of a product … outweigh the known and potential risks of the product.”

“I imagine that it is likely that the FDA will issue an emergency use authorization if any of the vaccines in development show significant and convincing evidence of efficacy and safety,” said Feinberg, whose research organization is collaborating with Merck to develop a COVID-19 vaccine.

Under an emergency use authorization, the vaccine could be administered before the completion of the Phase 3 trials, potentially helping to flatten the curve but giving scientists little time to study side effects or understand how it interacts with other vaccines.

Dr. Paul Offit, a vaccine expert at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, has raised concerns that the FDA would greenlight manufacturing and distribution of vaccines before the necessary reviews have been completed.

Offit worries that a vaccine with limited efficacy delivered prematurely might give people “a false sense of being protected” and “lead to serious outbreaks of the disease.”

“We should wait for the completion of Phase 3 trials, no matter how long they take,” he said. “With luck, they could be finished in six to nine months.”

But postponing the delivery date for a vaccine would not align with the January goal of Operation Warp Speed.

The Trump administration’s ambitious timeline has led to $5.7 billion being allocated to seven companies, and critics like Hotez and Offit wonder if speed is getting in the way of science.