WASHINGTON, D.C. — Many of the office suites reserved for top civilian officials at the Pentagon sit empty or have temporary fill-ins while Defense Secretary James N. Mattis worries about North Korea and Iran.

Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin lacks appointed loyalists in any of the 17 top spots below him as he rewrites the nation’s byzantine tax code.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson similarly relies on a skeleton staff to conduct global diplomacy, with dozens of jobs open.

And in the White House, President Donald Trump still depends on a communications director who resigned last month — because he hasn’t found a replacement.

More than four months after taking office, the president who built his brand telling people “You’re fired!” is having a hard time staffing up.

Working in the White House or as an aide to a Cabinet secretary is usually a career capstone, a chance to serve the country and sweeten the resume. But Trump has found it harder to fill out his administration than his recent predecessors.

It doesn’t help to have a special counsel investigation and FBI inquiry hanging over the White House, much of the GOP intelligentsia still chafing at Trump’s populist policies and widespread worry about his willingness to publicly undercut top aides with spontaneous tweets.

“I will not work for this administration (read into that what you may),” G. William Hoagland, who has advised Senate Republican leaders on budget policy for 25 years and is now senior vice president at the Bipartisan Policy Center, wrote in an email.

Hoagland, who said he was approached for the commissioner of the Social Security Administration job, cited “major differences of opinion” with the White House position that Social Security did not need changes to remain financially viable.

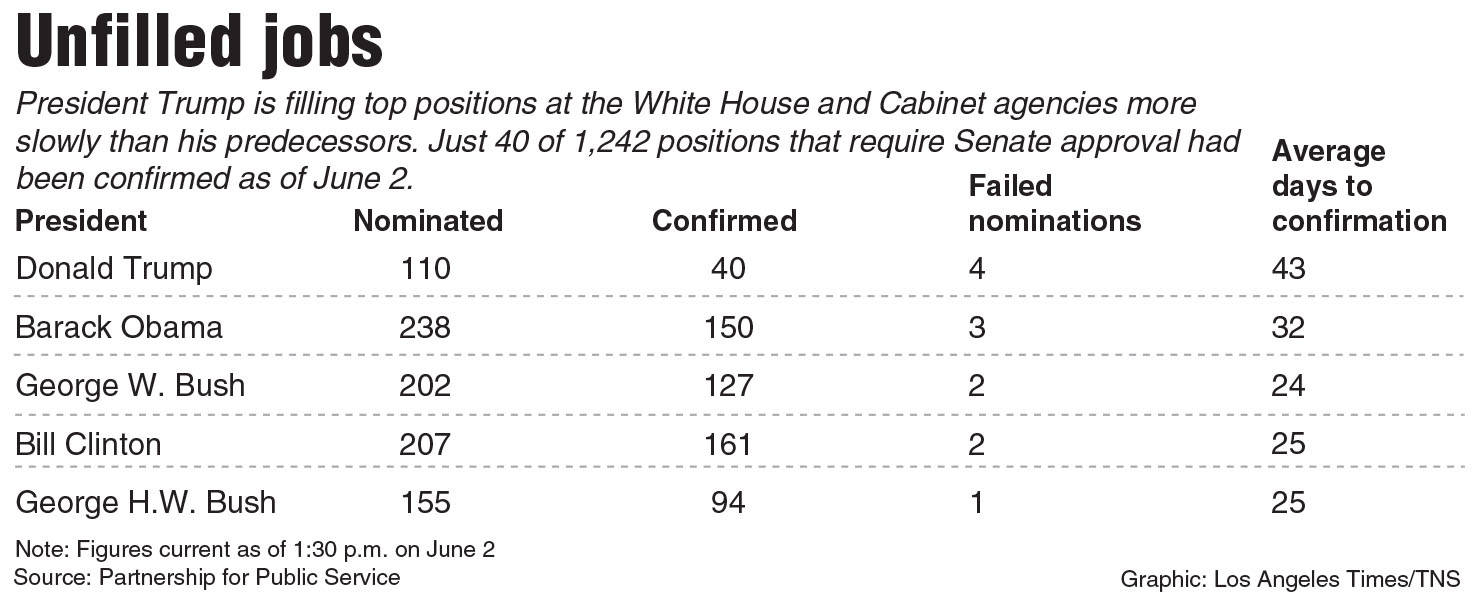

The Senate has confirmed nominees for only 40 of the 1,242 positions in the federal government that require a vote, according to the Partnership for Public Service, a nonpartisan nonprofit group that tracks jobs.

That compares with 94 confirmed for President George H.W. Bush at this stage in his presidency, 161 for President Bill Clinton, 127 for President George W. Bush and 150 for President Barack Obama.

The Trump administration complains that Senate Democrats have used arcane rules to stall the process that is otherwise controlled by the Republican majority.

But Trump also is far behind his predecessors in submitting nominations.

Obama, George W. Bush and Clinton each had nominated more than 200 people requiring a Senate vote at this stage. Trump has put 110 names forward.

“You come in with a checklist of things you want to accomplish,” said Tevi Troy, a top domestic policy adviser for George W. Bush. “It is harder to get those things done when you don’t have key people there.”

Adam J. White, research fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, said talk of “resistance” among the nation’s cadre of civil servants is not the biggest hurdle for Trump’s agenda. Rather, “valuable time is ticking away” as Trump fails to staff his departments with leaders who can provide direction and energy, he said.

“President Trump’s agenda of reforming and rolling back some of the regulatory initiatives by his predecessor, Barack Obama, requires serious work,” White said. “That’s the work of a massive political bureaucracy.”

The sluggish start, combined with hiring freezes for many positions, has rippled across the government because senior appointees want to hire their own teams. It also has slowed efforts to fill jobs that opened before Trump took office.

The Department of Veterans Affairs, the second-largest government department after Defense, has 45,000 vacancies — nearly 15 percent of its authorized workforce, Veterans Affairs Secretary David Shulkin has said.

The reasons are many, including the chaotic transition for an insurgent candidate who had a small staff and few ties to the GOP establishment.

As is normal in a new administration, some candidates have withdrawn their names because of potential financial conflicts or other problems.

But Trump also scuttled some applicants because they spoke out against him politically during the campaign in the media or on Twitter or Facebook.

Several people who have declined jobs do not want to speak publicly about it for fear of antagonizing Trump’s inner circle.

“People want that kind of job,” said a former aide to George W. Bush who considered a job in the Trump White House before opting out. “They’re just a little leery of all the wackiness.”

Williamson M. Evers, who headed Trump’s transition for the Department of Education, speculated that some would-be employees could be spooked by Trump’s plans to shrink large parts of the government.

“To ask somebody to tell their boss they’re leaving and to tell the children, ‘We’re going to a new school,’ … and then to say, ‘Oh, no, we’re not going to do that.’ You can’t really do that,” Evers said.

Trump’s sensitivity to the criticism he received from conservative intellectuals during the campaign has also played a significant role. It’s especially apparent in foreign affairs and national security, areas in which resistance to Trump among Republicans was deepest.

Just eight of 120 State Department posts, including ambassadorships, that require Senate confirmation have been filled, according to the Partnership for Public Service. Increasingly, foreign officials and diplomats struggle to find someone to discuss trade and security issues with.

Trump vetoed Tillerson’s choice of Elliott Abrams, a former adviser to Presidents Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush, to serve as his top deputy, in large part because Abrams criticized Trump during the campaign. That slot has since been filled by another candidate, John Sullivan, who was approved last month.

Others have been stricken for lesser sins.

Craig Deare, who was named National Security Council director for Western Hemisphere affairs in late January, was fired weeks later after he criticized Trump’s treatment of Mexico and the president’s policy team — including son-in-law Jared Kushner and chief strategist Stephen K. Bannon — during a private session with scholars at the Wilson Center think tank in Washington.

Trump’s first pick for Army secretary, Vincent Viola, blamed government rules that would have forced him to cut business ties when he bowed out. This problem has hit the Trump White House especially hard because the president initially drew heavily from the financial and business world for his picks.

Trump’s second pick for Army secretary, Mark E. Green, ran afoul of another standard. He withdrew after receiving criticism over his comments about Muslims and LGBT people.

Max Stier, president of the Partnership for Public Service, which is aimed at improving government effectiveness, said it would be difficult for Trump to catch up on his hiring after losing so much time.

Most of the aides who ran the transition are now engaged in the work of governing, leaving them less time to vet applicants.

The Senate also has become busier, leaving less procedural time to hold confirmation votes.

“They have a small group of people that have been responsible for making these personnel decisions,” Stier said. “Those are the same people who are worried about a Russia investigation, healthcare reform, tax reform, a North Korean missile test, the debt ceiling, the Paris climate accord. You name it.”