By Deborah Netburn

Los Angeles Times

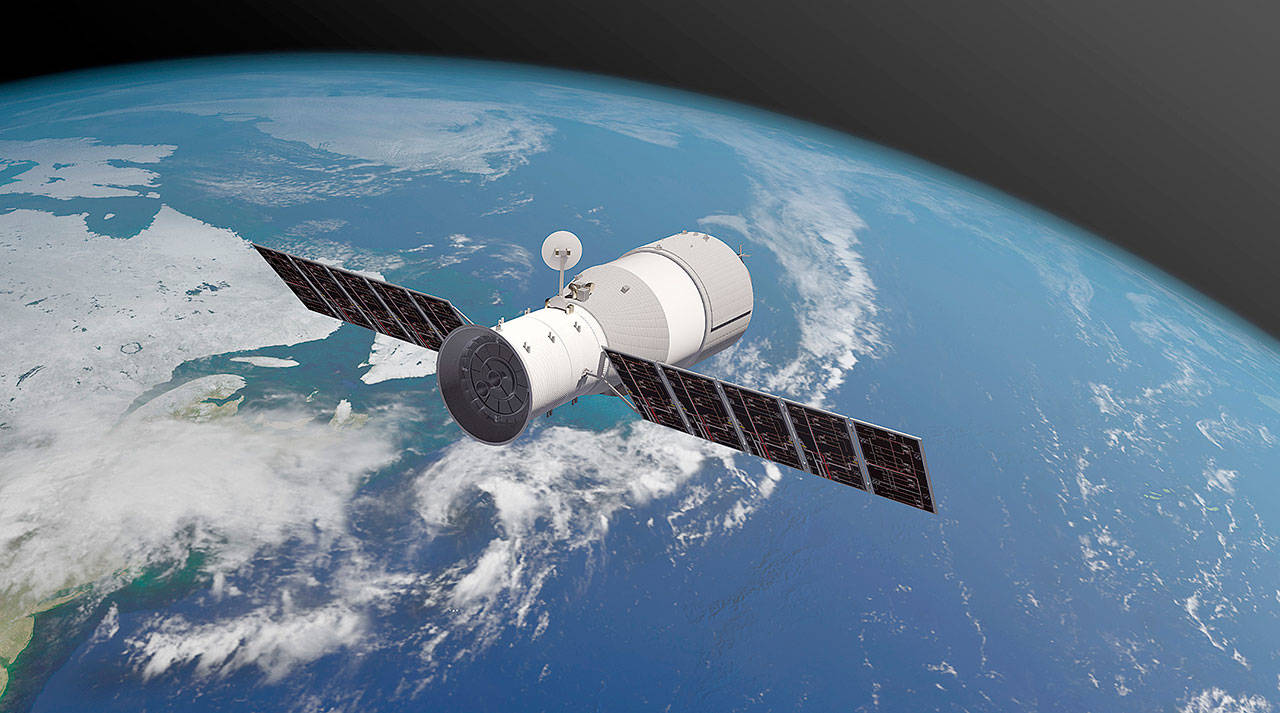

Sometime between Thursday and the middle of next week, the Chinese space station known as Tiangong-1 is expected to fall out of the sky.

Most of the 18,740-pound space lab likely will burn up in the atmosphere, experts said.

But not all of it.

Between 10 percent and 40 percent of the station’s mass probably will land somewhere on the planet.

As of now, nobody knows where.

Even predictions made 24 hours in advance about where the space station debris might wind up could be off by thousands of miles, said William Ailor, a researcher at the Center for Orbital and Reentry Debris Studies at the Aerospace Corp. in El Segundo.

But Ailor urges you not to worry. The chances of Tiangong-1 causing serious injury to anyone on Earth are extremely small, he said.

In the 60 years that humans have been sending objects into space, only one person has reported being hit by a piece of space debris. It was a small part of a Delta II rocket, and the victim from Tulsa, Okla., was not injured.

It also may be a comfort to know that man-made objects fall from space quite regularly.

“At least once a month, something of reasonable size comes down,” Ailor said. “You just don’t normally hear about it because they come down in some remote place in the ocean.”

(Remember, water covers 70 percent of our planet.)

Indeed, in the last couple of years, a few other objects in the same size range as Tiangong-1 — rocket bodies and other hardware associated with launching satellites — have fallen out of the sky.

Tiangong translates to “heavenly palace” in Chinese. It is relatively small for a space station, weighing in at just under 20,000 pounds. For the sake of comparison, the International Space Station weighs about 925,000 pounds.

Chinese officials have not communicated with it since December 2015, perhaps because of a malfunction with its power supply. Experts think that the space station’s reentry into Earth will not be controlled, although China has not said that explicitly.

Ailor is part of a team at the Aerospace Corp. that has been tracking Tiangong-1 since 2016. He spoke with the Los Angeles Times about why the space station is destined to fall, why it’s so hard to predict where it will land and why its reentry should be a pretty spectacular sight.

Q: I thought objects in orbit remain in orbit. Why is Tiangong-1 coming down?

A: Tiangong-1 is at a fairly low altitude of about 300 kilometers (186 miles) or so. It’s about where the ISS is in low Earth orbit. There’s not much air up there, but there’s some. The ISS actually has to be boosted every now and then because the atmosphere is slowly dragging it down. That’s what happened to Tiangong-1.

Q: Why is it so hard to predict when it will fall to Earth?

A: The basic uncertainty is what the atmosphere is doing. For example, if the sun has an event and spews material toward us, it could increase the amount of drag in low Earth orbit and cause the space station to fall faster.

Even slight variations in density at these altitudes affect the drag on a satellite traveling at about 4 miles per second and can make the decay rate somewhat unpredictable.

Q: Will you know more as we get closer to the day it lands?

A: Even if we had a prediction that was made one day ahead of time, we would have an accuracy of plus or minus 20 percent. That’s about plus or minus 4 hours or so in time. This thing makes one orbit around Earth every 90 minutes, so you can see that we can’t do too good a job of predicting where it will land, even a day ahead.

Q: What happens to space junk when it enters the atmosphere?

A: These items are traveling at 4 miles a second. When they hit the Earth’s heavy atmosphere, the temperature goes up and drag gets increased. That causes the temperature to go up even more.

Things like aluminum and some of the other materials that spacecraft are made of melt away pretty quickly. If the aluminum is holding something like solar panels, those will break off.

Q: How much of it will survive reentry?

A: Things that survive are usually relatively lightweight. We estimate 10 percent to 40 percent of the mass on orbit will come down and fall somewhere.

Q: But it won’t all land in one spot, right?

A: These pieces will be spread out over a footprint that can be as wide as 400 miles.

We have a 500-pound chunk of a stainless steel propellant tank that fell 50 yards from a farmer’s house in mid-Texas in 1997. It was part of the same Delta II rocket that brushed a woman walking in Oklahoma. From Tulsa, Okla., to mid-Texas is a fairly long distance, and there were fragments spread all along that path.

Q: I’ve read that some people think we should shoot Tiangong-1 before it crashes to Earth. Is that possible?

A: You have to be careful when it comes to shooting an object down. If you try to hit something in space, you can create a lot of debris, and we don’t want that because it increases the risk of debris hitting another object. There’s a real trade-off there.

Q: What’s the biggest thing to have fallen from orbit?

A: The biggest object we had come down uncontrolled was NASA’s Skylab in 1979. It weighed about 150,000 pounds. That’s a big object. Parts of it landed in Australia, but nobody was injured.

Objects such as the space shuttles and Mir were bigger but were under control and deorbited into specified locations.

Q: So, we really don’t need to worry about this?

A: It’s not a huge threat. These things come down occasionally, and we haven’t had a problem with them.

Q: Will it be possible to see the space station when it falls?

A: Yes, and it should be magnificent. It will be like a fireworks show with one object breaking into a lot of smaller objects. And you’ll see streams of light going across the sky.