By Hailey Branson-Potts and Ruben Vives

Los Angeles Times

LOS ANGELES — Parents whose children attended St. James Catholic School in Torrance, Calif., long believed that the campus was financially strapped.

Textbooks were two decades old. There wasn’t enough money for new basketball uniforms. When parents would ask, year after year, for an awning to shade their children’s outdoor lunch area, the principal, Sister Mary Margaret Kreuper, would respond, “How do you expect to pay for it?”

“We would be pressured into donating,” said Jack Alexander, whose three children attended the K-8 school from 2003 to 2016. “We were always told how little money we had and how the sisters were so poor.”

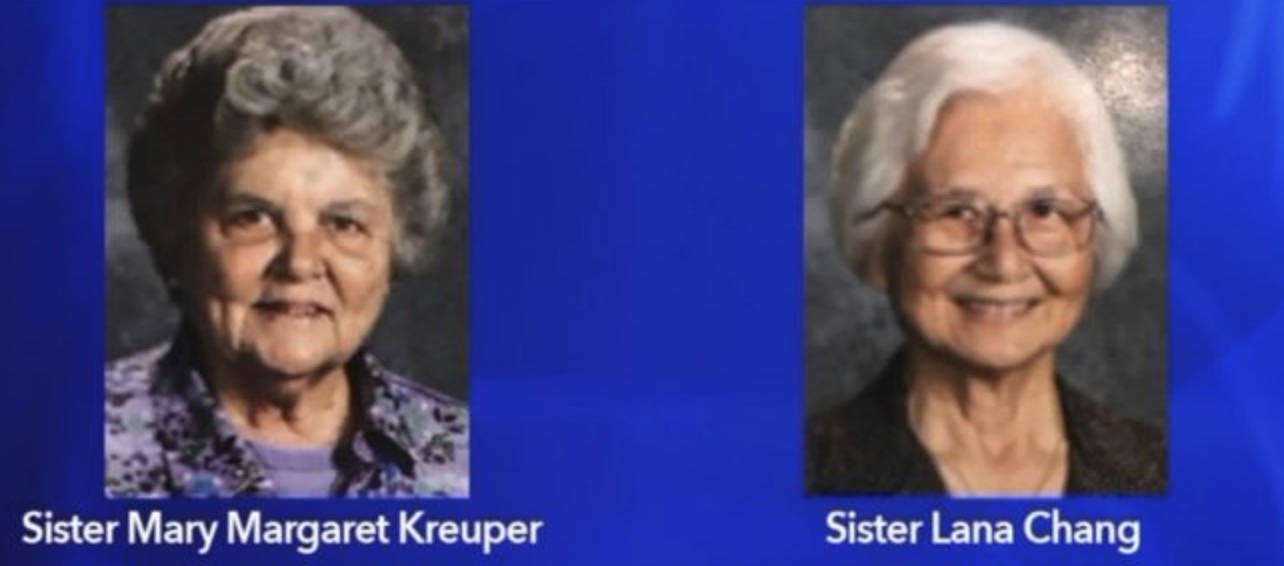

All the while, Kreuper and her vice principal, Sister Lana Chang, spoke openly about trips they’d taken to Las Vegas and Lake Tahoe, parents said. The nuns lived together for years in a townhouse in a gated Torrance neighborhood and pulled up to campus in separate Volvos. Chang, they explained, had wealthy relatives who provided for them.

In truth, the pair had been stealing from their students’ tuition checks, fees and fundraisers for at least 10 years, school officials and auditors told parents at a raucous meeting at St. James Church in Redondo Beach this month.

Kreuper and Chang, they said, diverted at least $500,000 into a long-overlooked church bank account that they used to cover their expenses. Auditors working with the Archdiocese of Los Angeles said that figure probably will rise as the internal investigation continues, because the bank only had records dating back to 2012. The account was opened in 1997.

Neither the nuns’ order nor the church disputes that the pair took the money.

“We do know that they had a habit of going on trips,” Marge Graf, an attorney for the archdiocese, said at the Dec. 3 meeting with parents and alumni. “We do know they had a pattern of going to casinos. And the reality is they used the account as their personal account.”

Many parents have reacted with shock and outrage as details of the theft have come out in recent weeks. The Los Angeles Times obtained an audio recording of the two-hour meeting at which the situation was discussed. At one point, Graf asked the audience to delete any recordings of the meeting or to keep them private, drawing audible snickers from the crowd.

“If this was me, I would be in jail!” one man yelled.

Kreuper, 77, and Chang, 67, both retired from St. James School last spring. Kreuper was the principal for 29 years; Chang was an eighth-grade teacher for two decades and the vice principal for the last several years. Neither could be reached for comment.

The archdiocese initially said it would handle the investigation internally and not press charges, outraging parents who said they were tired of the Roman Catholic church continuously trying to hide its scandals.

This week, the archdiocese reversed course, saying it was cooperating with police and planned to become a complaining party in a criminal case.

Adrian Alarcon, a spokeswoman for the archdiocese, said the plan to handle the matter internally had stemmed from a promise by the nuns’ order, the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, to repay the stolen money. The archdiocese changed its mind, she said, because the amount of the funds purloined —which has not been confirmed —had grown so large.

Sgt. Ronald Harris, a spokesman for the Torrance Police Department, said a criminal complaint has not yet been filed. School officials told police in late November that a large amount of money had been embezzled over a long stretch of time, but they declined to press charges and did not give enough details to allow police to conduct a proper investigation, he said.

“We had little to go by until a few days ago, when the department was advised that (church) officials want to press charges,” Harris said.

Msgr. Michael Meyers, the pastor at St. James Church, told parents that the con came to light during a routine financial review last spring after Kreuper’s retirement. At about the same time, he said at the recent meeting, a family requested a copy of an old check to the school and noticed that the endorsement on the back was not for the school’s primary account.

On Nov. 28, Meyers sent a letter to families about the theft, saying Kreuper and Chang had expressed “deep remorse.”

“Let us pray for our school families and for Sister Mary Margaret and Sister Lana,” he wrote.

The Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, an international congregation, said in a statement this week that Kreuper and Chang “take full responsibility for the choices they made and are subject to the law.” They have been “placed in a religious house under the supervision of community leadership” and removed from public ministry, the order said.

Alexander, a Redondo Beach real estate appraiser, said he had numerous confrontations with Kreuper while his son and two daughters attended the school.

He was a volunteer football, basketball and golf coach. One year, after the school hosted a golf tournament, Kreuper accused him of stealing $3,000 from the event. The money was later found on her desk, Alexander said. Parents, he said, were always wanting to start new sports teams and have more events, only to be told there wasn’t enough money.

Alexander said he never seemed to have any $5 or $10 bills for years because he was constantly being asked to donate.

Annual tuition for St. James parishioners ranges from $4,400 for one student to $10,760 for three, according to the school. Parents were not able to pay online and had to hand-deliver checks or send them in church collection-style envelopes, Alexander said.

The scandal has been devastating for families of St. James Catholic School, which celebrated its 100th anniversary this year. The modest Anza Avenue campus consists of three stucco and red-brick buildings. On Tuesday, children could be heard inside singing “Give Me an Old-Fashioned Christmas.”

The congregation with which it is associated, St. James Catholic Church in Redondo Beach, has endured other recent traumas. In 2014, an intoxicated woman drove her car into a crowd of people leaving a Christmas concert and killed four people, including a 6-year-old boy.

Meyers previously oversaw background checks for priests as the archdiocese’s vicar of clergy, but resigned in February 2011 after it was discovered that a San Dimas priest he had vetted previously had admitted to sexually abusing a teenage girl. He took over as pastor of the Redondo Beach later that year.

Denise Sur, a St. James parishioner whose four kids attended the school, said the church bungled its communication with parents over the theft, waiting months to tell them about the internal investigation, then declining to provide details. Sur said that though she wasn’t defending the nuns, she thought they were getting more scrutiny than priests accused of sexually abusing children and that there was a double standard.

“Why did they make this into a media circus?” Sur said.

Like many parents, Sur defended the education her children received at the school but said Meyers and the archdiocese have failed in their oversight of it.

At the Dec. 3 meeting, angry parents asked Meyers if the nuns would personally apologize to families.

“If they come here to ask your forgiveness and ask your understanding, and if you’re going to sit here and throw tomatoes at them, no, I don’t think they ought to come,” Meyers said.

Some parents who are revising their past views of the school’s administrators also wonder what further digging may reveal.

Debby Rhilinger, whose five sons attended the school over 16 years, recently asked for copies of $45,000 of old tuition checks from her bank and discovered they were diverted to the false account. She said she expects much more was stolen from her family because her bank had check records for only seven years. Kreuper endorsed each check by hand.

Rhilinger, who once had considered Kreuper a friend, said the nun ran a tough but excellent school. She visited the principal in April and asked why she was retiring.

“She said, ‘It’s time. The parents that are coming through here now, this younger generation, they just feel so entitled,’” Rhilinger said. “It’s like, are you serious? You felt entitled to take everybody’s money.”

Rhilinger said so much now seems suspicious. Every fall, the school holds a Harvest Festival fundraiser, with rides and food booths. Families each had to put in $100 and buy a ticket for the Big Red Raffle, she said. Chang was one of the raffle winners every year, Rhilinger said.

“When her name got pulled, she would say, ‘Oh, my gosh! I can’t believe it!’” Rhilinger said. Now she thinks it was rigged.

As publicity escalates around the embezzlement, the scandal has driven a wedge between families —with many saying that they want to press charges and others saying the Bible tells them to forgive, Alexander said.

“It’s the difference between faith and blind faith,” he said. “We’re people of faith, but we know what’s right and wrong. … These are crimes committed against hundreds of children.”