By Tom Quigg

To me, Sunset Memorial Park Cemetery has always been an intriguing place. As a young boy in Hoquiam it was interesting to wander around the old section in the southernmost part. Even in the 1950s many of the tombstones from Hoquiam’s earliest days had become unattended and over grown with brush. The coolest part was the old access road that came up from Lincoln Street, parallel to Grand Avenue. At that time it was overgrown to just a trail through what was once a single-lane rock road, with an occasional rock retaining wall in the steep sideslopes. I would imagine that it was designed just wide enough for a single horse drawn hearse, followed by a long line of mourners.

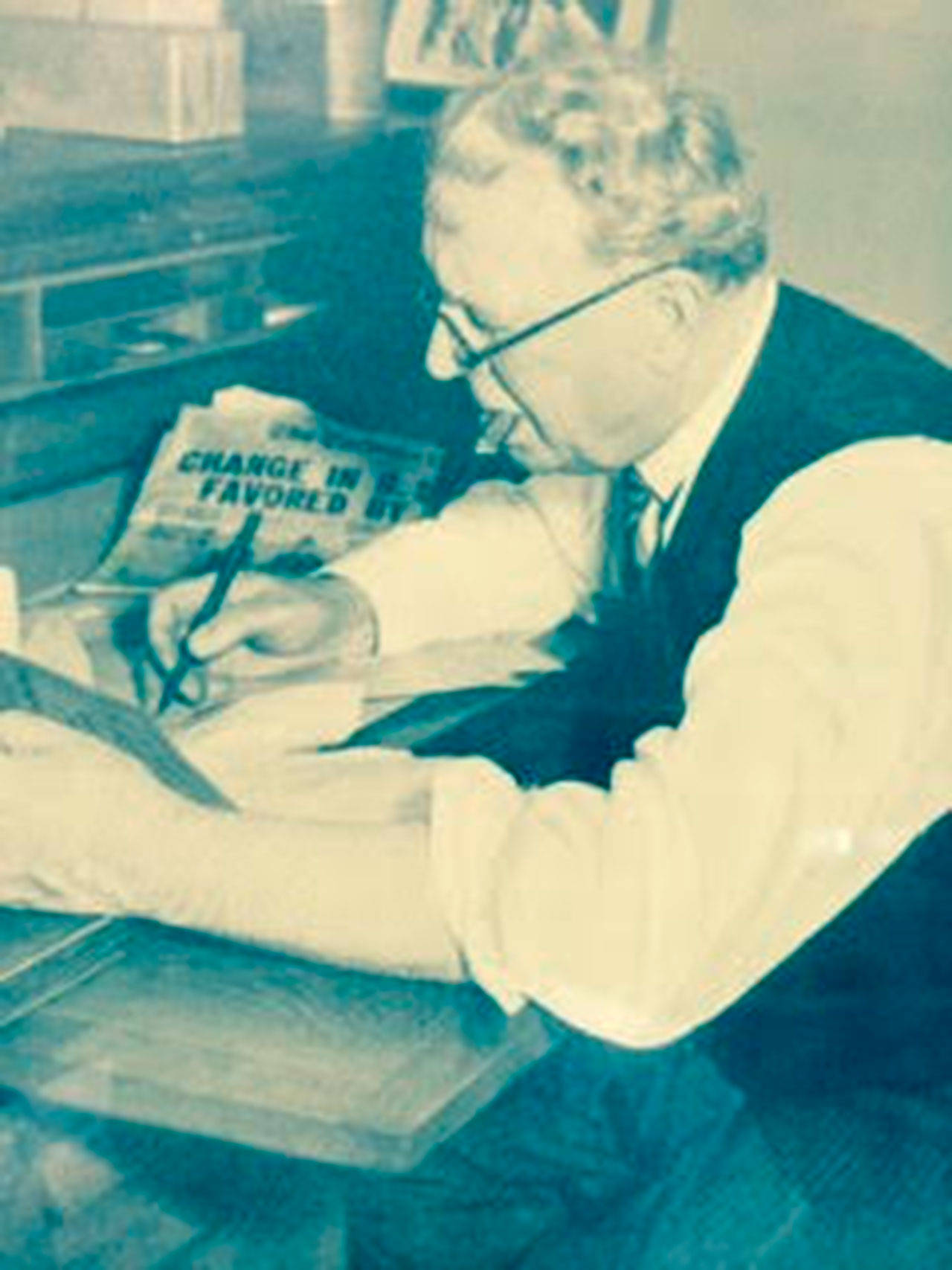

It’s always been a history lesson for me to just walk down the aisles of tombstones, and recall names of people I’ve heard of, or known. Recent decrees made by the current U. S. President, caused me to recall one person in particular who is buried in the cemetery. So, I went on a mission to find the gravesite of one of Hoquiam’s citizens of the past. I sought the help of Tracy Wood, who among her many duties with the City of Hoquiam, oversees the operation of the Sunset Memorial Park. With her plat map in hand, Tracy walked me right to the gravesite of Albert Johnson, and his wife Jennie Smith Johnson. Albert was the editor of The Daily Washingtonian in Hoquiam, and Republican U. S. Congressman from 1913 to 1933.

I’d like to tell you about Albert, and the imprint his work made on America as we know it. My story is not to draw any opinion, but just to inform you how history may be repeating itself, from what began right in my hometown of Hoquiam.

According to an essay posted on HistoryLink.org by Aaron Goings, Albert Johnson became one of the most powerful congressional leaders in the United States. According to Goings, “Johnson’s political interests varied widely from his support of woman (sic) suffrage and editorial assaults on monopolies. But the two defining characteristics of both his life in Hoquiam and his service as congressman were his militant opposition to radical labor unions and his hatred of immigrants.”

He is most remembered as the author of the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act. Jim Scott writes in Festschrift, 1994, that “History has neglected Congressman Albert Johnson, ‘Father of the 1924 Immigration Bill.’ The act codified the concept of admitting aliens into the United States on the basis of quotas.” In a biography on the congressman, written for Pacific Northwest Quarterly in 1945, Alfred J. Hillier referred to the 1924 bill as “the most important immigration law to be enacted in the history of the country.” The bill was reported to be designed to limit immigration to favored European nations, based on 2 percent of each nation’s population within the United States, with a maximum of 150,000 per year. According to Goings, “the act excluded from entry anyone born in a geographically defined “Asiatic Barred Zone,” which included most of the continent of Asia.

Long before the internet was even a dream, Albert Johnson published The Daily Washingtonian, and a second newspaper he called the Home Defender. Johnson was noted for his strong views, and Goings writes that “the Home Defender carried ‘news’ and opinions that would have shocked the more subdued Washingtonian subscribers.” I wonder if by placing ‘news’ in quotes, he was equating it to what today is referred to as “fake news,” or “alternative facts.”

Goings adds that while working with the minority Republican Party in Congress, Congressman Johnson worked to establish the Home Defender as “A National Newspaper Opposed to Revolutionary Socialism” (Home Defender, March 1914).

According to Goings, “in one Home Defender harangue” the Congressman suggested that the United States “Put up the Bars” against immigration: “The character of immigration has changed and the newcomers are imbued with lawless, restless sentiments of anarchy and collectivism. They arrive to find their hopes too high, and the land almost gone and themselves driven to drown in the cities and struggle for a living. Then anarchy becomes rife among them. (Johnson, “Put Up the Bars”).” You can read the entire Goings essay by search HistoryLink.org for Albert Johnson.

In 2003 a British author by the name of Kristofer Allerfeldt published the book “Race, Radicalism, Religion, and Restriction – Immigration in the Pacific Northwest 1890-1924.” He did extensive research on the topic, much of it in Hoquiam. It was his opinion that although there was a lot of hostility toward immigrant groups after World War I, the Pacific Northwest exerted more pressure on the national legislature than any other region. His conclusion said in part that there was a primary leader in this pressure. “In large measure this was the result of the work of one man. If the region has one claimant … it must be given to Albert Johnson.” He adds that “Johnson was re-elected on his anti Japanese, anti-radical, anti-Slavic—anti-immigrant (sic) — plank for over 20 years, only losing his seat in the 1932 landslide.”

Albert Johnson came to Hoquiam over 100 years ago. Was Johnson’s The Daily Washingtonian, through its companion newspaper, the Home Defender, the forerunner of some of today’s online opinion websites, or certain Twitter.com accounts? I’ve always said that all roads pass through Grays Harbor, and much of today’s news on immigration sounds very similar to what Congressman Albert Johnson published 90 to 100 years ago. I’ll leave to you to decide in your own mind if history has repeated itself.

By the way, my first job for pay was as a delivery boy for The Washingtonian. By the mid 1950’s it had become a weekly, and no longer printed political opinions like those of Albert Johnson’s. The stories were primarily of community interest news. As delivery boys, we got paid a silver dollar when the newspapers were neatly rolled, in the delivery bag, and passed the inspection of the circulation manager, J. Val Dalby. We were trusted to make the delivery, even though we had been paid in advance. My 1950’s memory of The Washingtonian was J. Val Dalby, and his very valuable lesson of verifying his people were prepared for the job at hand, and trusting that we would do the right thing. He was a very wise and nice man.

Tom Quigg is a longtime Realtor on Grays Harbor and the author of “The Harbor — A Culture of Success,” a book about people from Grays Harbor who are nationally or internationally known in their fields.