In Washington, a record number of citizen led initiatives made it to the Democratic controlled legislature last year.

All were Republican backed.

That isn’t a surprise, according to researchers.

State legislatures dominated by one political party can leave minority constituents feeling voiceless. In 20-some states, including Washington, laws grant citizens a lever of control that does not require support from their state representatives.

It also isn’t a surprise that state lawmakers are introducing proposals to complicate the process. In fact, it’s a long standing trend, said researcher John Matsusaka.

A senator in Olympia introduced a bill that would require additional voter verification steps for the Secretary of State’s office and for signature gatherers to sign a declaration on each sheet of signatures they collect — steps that Republicans, the Democratic Secretary of State and supporters of the initiative process say would make the process much harder.

“Chipping away at the initiative process is a perennial activity,” said Matsusaka, Executive Director of Initiative and Referendum Institute, a nonpartisan research organization.

What makes Washington unique is who has championed the bill.

Matsusaka’s research found that the strongest predictor of anti-direct democracy proposals is Republican control of the state legislature.

Here, with their current majorities, Democratic lawmakers can pass policies on health care, housing and taxes regardless of Republican opposition. Yet prime sponsor Democratic Sen. Javier Valdez, from Seattle, said his bill was “essential to ensuring Washington’s initiative process remains fair, transparent, and free from fraud.

Ultimately, Matsusaka and others say, regulating initiative processes seems to come down to power.

“In a world of partisan polarization, it’s eerie how both parties do the same playbook once they’re in power,” Matsusaka said.

How do initiatives come about?

Following the 2022 U.S. Supreme Court decision striking a federal right to abortion, Republican-controlled legislatures in Arizona and Missouri passed laws restricting abortion.

Advocates answered back in 2024 with citizen measures and, with voters’ approval, both states established abortion as a fundamental right in their constitution.

This year, both state legislatures saw proposals that would make direct democracy processes more difficult.

As in Washington, those proposals angered the opposing party, and people who rely on the initiative processes when their issues are not prioritized by power.

“They think they know better than the people, and they want to quiet the peoples’ voices in the initiative and referendum processes,” said Rep. Jim Walsh, R-Aberdeen, who chairs the Washington GOP and worked closely with conservative millionaire Brian Heywood to qualify initiatives in 2024.

The Washington state constitution grants citizens the right to initiatives and referendums. Initiatives can be used to create, modify or repeal laws while referendums are used to veto laws.

Initiative sponsors file measures with the Secretary of State’s office. They choose whether to file an initiative to the people, meaning it goes directly on the next general election ballot or an initiative to the legislature, which gives lawmakers the opportunity to pass the measure as written.

If lawmakers amend the initiative or choose not to take action on it, the measure is sent to the general election ballot for voters to decide.

The cost of an initiative

Qualifying initiatives is a feat that requires time and money.

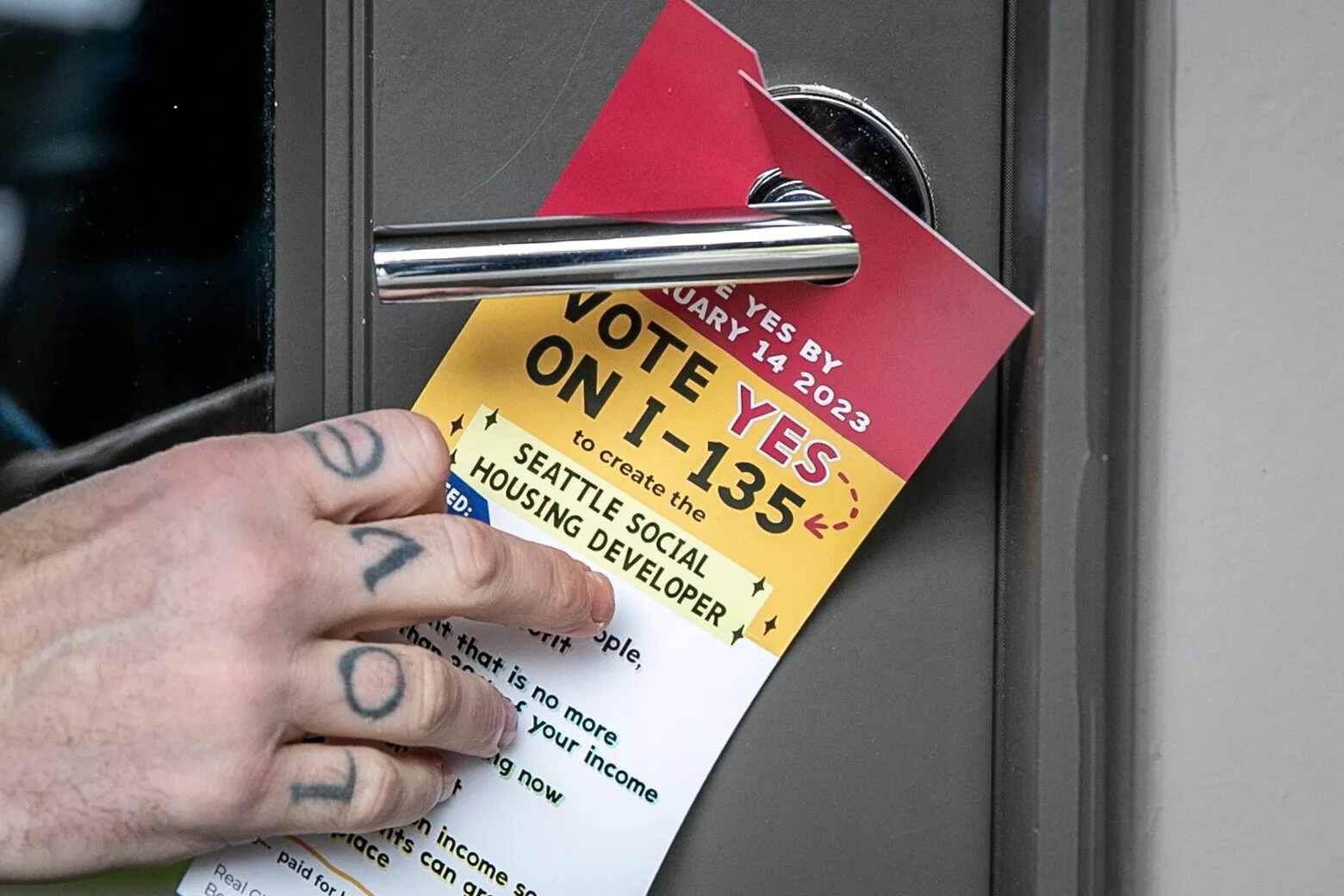

Heywood and his advocacy group Let’s Go Washington funded six initiatives to the Legislature and one to the people in 2024. His proposed policies ranged from a parental rights bill to repealing climate protections in Washington’s Climate Commitment Act.

Heywood’s initiative efforts have cost him millions. He said the investment is worth it.

“I don’t believe that the initiative process is the best way to make new law,” Heywood said. “I think that it should be debated in the Legislature. The challenge we’ve got in our state is that the Legislature has completely become captured.”

The Legislature passed three of Heywood’s six initiatives that came before them. The remaining three were left to voters who rejected all of them in November.

The singular initiative to the people, which proposed repealing restrictions on natural gas, was approved by voters. However, a King County Judge ruled it unconstitutional last week.

With a sympathetic legislature, left-leaning groups aren’t as quick to file initiatives.

“It’s just easier, simpler and less expensive to pursue legislation,” said Andrew Villeneuve, founder of the Northwest Progressive Institute. “It’s also, sometimes, a way better result.”

Who’s using the system

The process hasn’t been exclusively used by one party. Democrats’ policies — from the right to abortion to raising the state’s minimum wage — have passed via initiative.

But the fact that the process has previously been and might in the future be useful to Democrats doesn’t matter much now, according to Todd Donovan, professor of political science at Western Washington University.

“You’ve got power, you want to keep power. It’s not a partisan thing as much as who’s the majority party thing,” he said. It’s similar to how politicians often change their position on open primaries and term limits depending on who is in power.

In fact, Diane Jones was the sponsor of Initiative 735, a successful progressive measure in 2016 that established state support for a federal constitutional amendment to reserve rights in the constitution to human beings.

Jones said — even without these new restrictions — it was extremely difficult to rally support for the measure and develop the volunteer network necessary to gather approximately 300,000 signatures.

The spirit of Jones’ Initiative 735 was to keep “big money” out of elections, so Jones tried to use all volunteers for the effort. Administrative and printing costs the campaign more than $400,000.

Volunteers collected approximately 274,000 signatures and paid signature gatherers helped to collect about 58,000, according to Jones. The signature gathering cost an additional $120,000.

In Washington, an initiative needs signatures from registered voters equal to 8% of the votes cast in the last governor’s election to qualify. With a cushion to account for invalid signatures, that number comes out to 386,000 signatures in 2025.

Most sponsors fall short of the signatures needed to qualify their initiatives. In recent years, almost all successful initiatives, including Democratic ones, used some form of paid signature gathering. Jones said it’s the massive financial investments into initiatives that concerns her.

“Heywood bought this way onto the ballot; that doesn’t seem very democratic to me,” she said.

Heywood spent more than $10 million on his 2024 initiatives according to data from the Political Disclosure Commission. Almost $3 million was spent on signature gathering, nearly $4 million was spent on advertising, and the remaining $3.6 was spent on ‘miscellaneous’ costs.

Unpopular but proposed

Part of the Senate proposal would require all signature gatherers to sign a declaration on each sheet of signatures, under potential penalty of a fine and jail time, that each person willingly reviewed and signed the petition with their true name.

Fear of legal risk might scare volunteers. It would likely be grassroots efforts like Jones’ more than Heywood’s that would be hurt by the new regulations.

“The regulations are pitched as making the process more democratic by preventing abuses. But in my experience, they are almost all solving a problem that’s never been shown to be an actual problem,” Matsusaka said.

New regulations have also proven unpopular in other states.

In Missouri, some voters are protesting as Republican lawmakers push to raise the percentage needed to pass a constitutional amendment from 8% of registered voters in two-thirds of the eighth congressional districts to 15% of voters in all congressional districts.

Arizona voters already rejected two GOP November propositions which would have made it harder for citizen measures to qualify for the ballot.

Valdez’s legislation died in committee days after the current Democrat and former Republican Secretary of State testified against it, calling it unnecessary and expensive. Valdez declined to be interviewed by The Seattle Times but wrote in an email that “SB 5382 does not make it harder to qualify initiatives — it makes them more legitimate.”

Whether Washington Democrats intend to revive Valdez’ bill or pursue future legislation to further regulate the initiative system remains unseen.

But Heywood intends to build off his momentum regardless of voters rejecting several of his 2024 measures.

“I’m very much interested in a Legislature being held accountable,” Heywood said in reference to future initiatives he is considering.