There are a lot of things Marines take home from battlefields, from deployments.

Patches and headwear in foreign designs. Knives and insignia and jewelry, perhaps traded, perhaps taken from those who no longer have a use for it, for they no longer have a use for anything. Gifts for those beloved to them, perhaps. Rocks that have acquired some value out there, far from home, carrying luck or curses or simply because they caught someone’s eye. Memorabilia more macabre, if they feel they’ve earned it or can get away with it.

When Jim Evans returned back to Grays Harbor County from the Korean War, one of the Chosin Few to survive the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir, he brought a rifle home with him.

The Mosin-Nagant is a common name for a Russian bolt-action rifle, introduced into service before the end of the 19th century. Chambered for 7.62 x 54mmR (rimmed) cartridges, the rifle is more than five feet long, with wooden furniture that is less squared off, perhaps, than many of its contemporaries of the era, such as the Lee-Enfield or the Mauser. The action can be a little finicky for shooters unused to it.

Tens of millions were produced, distributed across the world, and used, such as the one Evans found in North Korea, bereft of its bolt as it lay there, abandoned in the bloodstained snow.

Bringing it home from the war, Evans said he was eventually forced by circumstances to part with it.

“Shortly after I got back, I had some financial issues. I sold it to a friend with the idea that I could buy it back from him,” Evans said in an interview. “One thing led to another, and I never did get back to him, and he sold it. He’s since expired.”

Over the years, Evans said he’s cast about a few inquiries, trying to find it again. At 95 years old now, he said he’s hoping to pass it on to family.

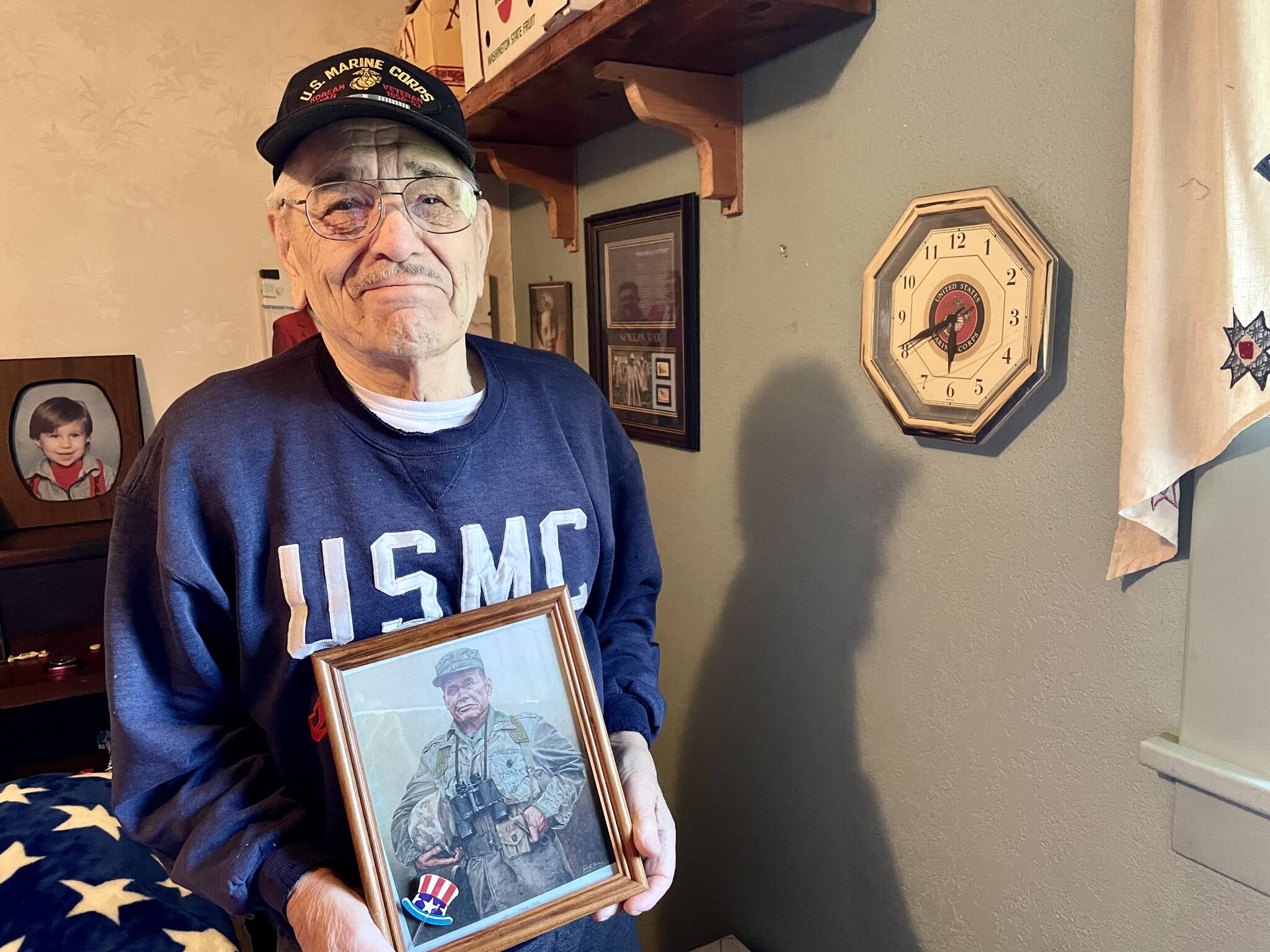

“I touched a base here and there,” Evans said, sitting comfortably in his living room, accented visibly with the flavorings of the Marine Corps. “I didn’t make that big a deal. But the older I get the dearer those things become.”

Over cold and broken stone

Evans had joined the Marine Corps Reserve for reasons that some may empathize with.

“It seemed like a good idea at the time,” Evans said. “They gave us a little money and a set of clothes and there was a certain amount of charm to it. It seemed to be the thing to do.”

When the Korean War broke out, Evans was mobilized, along with dozens of others in the area.

“I was with the group that left Aberdeen. I think there was about 60 of us,” Evans said. “There were WWII veterans. I turned 21 in the middle of it. A lot of them were 17, 18.”

Initially sent to Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, Evans didn’t spend long there before being routed to the front via Japan.

“I got four weeks of combat training and I was called into the first sergeant’s office. He had my record laid on the table there and he was checking me off,” Evans said. “On the front of my folder, it had a big ‘CR’ stamped on it in red ink about four inches high. I said ‘sergeant, what does CR mean.’ And he said, ‘son, it means combat ready.’”

Evans made the crossing aboard a troopship, joining up with other forces in Japan before entering Korea.

“When we were in Japan, we did some field exercises,” Evans said. “They called a stop and I saw a four leaf clover and I picked it and I still have it today.”

Shortly after finding that clover, Evans would depart for Korea, landing unopposed on the eastern coast as allied forces routed the North Korean military, rolling back their gains and pushing well past the 38th parallel.

“I got into Korea on or about the 8th of November. Right after my birthday,” Evans said. “Wonsan. It was a peaceful landing.”

Evans joined the 1st Marine Division as it pushed north, into the brutal North Korean winter landscape. Evans would join 1/1-1st Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, under the command of Marine Corps legend, Col. “Chesty” Puller.

“There was a train ride. It was cold. Boy, was it cold,” Evans said. “We were in open-gondola cars.”

Entrained on open train cars in the deepening cold and headed north, Evans had the opportunity to demonstrate a useful skill set to his fellow Marines, quicker than perhaps anticipated.

“My feet were freezing. Being from the Pacific Northwest, I knew how to make a fire. Korea at that time, there were 50-gallon barrels everywhere,” Evans said. “When the train stopped, we jumped off and grabbed a barrel. Our car was pretty happy because of that fire.”

At the end of the train ride, Evans would join the other Marines in trucks, headed north to reinforce the winter offensive ordained by Army Gen. Douglas MacArthur, bound for the anvil of the Chosin Reservoir.

Into the crush

The Chosin Reservoir marks the furthest northern advance of United Nations forces during the war, and the battle where the Chinese People’s Liberation Army entered the war.

More than 100,000 Chinese soldiers of the 9th Army, who had crossed the border in secret, slammed into advancing Army and Marine Corps forces. U.S. forces were dangerously overextended, warned Marine Corps commanders at the time, and that November, over ground as cold and hard as iron, the Chinese and U.S. forces became locked into some of the most brutal combat of the war.

“The first time I heard incoming rounds, I wondered if I hadn’t made a mistake. If you’ve heard ammunition passing you by you’ll know of what I speak,” Evans said. “The first incoming rounds I heard were from a long distance. They kind of went ‘zzzz.’ They weren’t small rounds. They were long range rifle shots. It’s what a deer hears when you miss.”

Evans served as an ammo carrier, bringing boxes of .30 caliber rounds to slake the endless hunger of the M1917 Browning machine guns.

“Ammo carriers were known for their long arms and their knuckles, dragging the ground from carrying two cans of .30 cal,” Evans said.

Evans moved with his unit, taking up position south of the dam structure itself.

“That night when we arrived — I think it was Hill 1081 but I’ve never been able to verify that. We struggled up that son of a gun,” Evans said. “I think Charlie Company took that hill and we occupied it later.”

The offensive was supported by a massive concentration of Marine Corps and Navy air power; F4U Corsairs operating in a fighter-bomber role brought machine guns, rockets, bombs and napalm down in close coordination with Marines on the ground, buying them space and allowing U.S. units to break free and make a fighting retreat.

“I have remembrances of … it was early morning. There was no snow. It was a clear day. Word came by to break out the air panels,” Evans said. “These aircraft come down, with the inverted gull wings. I think they called them Corsairs. They cut loose with rockets and machine gun fire. It was a glorious sight.”

Attack aircraft held Chinese forces distant from his position, Evans said.

“There were Chinese … at least, I assumed they were Chinese,” Evans said. “We never got close. They just laid waste to them.”

The unit never made direct contact while on that hill, Evans said. But as forces made their fighting withdrawal, Evans found himself bumped to machine gunner from his role as “Ammo Carrier Number Seven.” Evans would operate the M1917, a water-cooled machine gun capable of laying down sustained, effective fire.

“At one point, I don’t know what happened to the machine gunner or the a-gunner or the other six ammo carriers but the lieutenant said, ‘Evans, take the gun,’” Evans said. “I didn’t know a hell of a lot about that gun. It was a wonderful piece of gun.”

As the allied forces pulled back down the single road to Wonsan on the coast, elements became jumbled, as everyone did what needed to be done to maintain the pace and keep the Chinese forces at arm’s length.

“The plan was the 5th and 7th (Marine) Regiments would pass through us and we’d pull up the rear,” Evans said. “People got kind of interlocked between outfits. Wherever you fell in, you did whatever needed to be done to pick up the slack. When an officer said ‘come along,’ you went along.”

The rifle

It was after the battle that Evans would find the rifle he’d eventually take home.

“Concerning the rifle, it was night time. We had set up on this hill after the Chosin withdrawal,” Evans said. “That day when we set up, we dug in. I had set up the machine gun so I was all set up, so I could traverse.”

Evans identified a boulder as a likely avenue of approach for Chinese forces against the Marines’ position.

“I think it was around midnight and they popped a flare. There was some action out front and the word came down,” Evans said. “I heard some snow crunching so I let off a few bursts. We figured out later, they were probing, seeing where (the Marine defenses) were weak.”

Evans found the Mosin-Nagant on the ground near the boulder the next morning.

“The next day we were looking and we could see some blood on the snow. I found the rifle but there was no bolt in it. There was no bolt in the rifle but it looked like it was in pretty decent shape so I held on to it,” Evans said. “I went through four or five bolts trying to find one that fit the rifle. I brought the rifle home and the bolt had a different serial number.”

The Mosin-Nagant comes in two patterns — a rifle and a carbine pattern, with the carbine pattern being somewhat shorter. The version Evans found was the rifle, considered less desirable, he said. Other weapons, including submachine guns and sidearms, also found their way back stateside, claimed from the dead by Marines.

“We had one fellow that had a pistol, it took something like a 9mm (round). Russian make,” Evans said. “I know the officer came along and said, you have to turn that in. I know damn well that pistol didn’t get turned in, it went home with the officer.”

Evans had the chance to gauge the quality of the Mosin-Nagant after returning stateside, he said.

“It was a good shooting rifle. I had a chance to shoot at a man-sized target at 1,000 yards against M1s,” Evans said. “I hit it three out of five times which is pretty good shooting with no sights.”

Evans continued his wartime service until late 1951, though not before being wounded.

“I did manage to get a Purple Heart later in the campaign,” Evans said. “An explosion happened. Everything went up, and a piece came down and hit me. My buddy says, ‘hey, you’re bleeding.’”

Returning home

Evans returned stateside, posted at Camp Barstow, California, now Marine Corps Logistics Base Barstow. After mustering out, Evans returned home and like many other veterans of many other wars, settled down and found a job.

“I went back to work at the tire shop,” Evans said. “I worked there for a total of about eight years.”

And again, like many other veterans of many other wars, that reentry wasn’t flawless. Evans said there were still aftereffects from combat reactions that he had to live with.

“I was having lunch and a damn jet went over and made a hell of a racket,” Evans said. “I looked up at it from the floor. Everyone was looking at me like, what the hell are you doing there.”

While some of that might have mellowed out over the years, Evans said some of it is still with him.

“You never completely readjust,” Evans said. “After 75 years you’d think you’d lose some of that. Maybe I have lost some, but not all of it.”

Evans said that opening up about his experiences, talking to people, has helped him ease some of the weight he’s carried since coming home.

“I find the more I talk about it, the easier it becomes,” Evans said.

Now, Evans said he’s looking to find that last connection with his time in Korea: the rifle itself, with its bolt from another weapon.

“The bolt was bright metal, compared to the rest of the piece,” Evans said. “If it’s in someone’s closet I’d be willing to purchase it back at a fair price.”

The rifle isn’t for him anymore, but as something to pass along to family, Evans said.

“It may have changed hands half a dozen times, 75 years is a long time,” Evans said. “I don’t have a lot of time left, and I don’t think I’d be interested in selling it, but I’d like to pass it along to my grandson.”

Anyone with information about the possible whereabouts of the rifle is asked to contact Evans at 360-532-3843.

Contact reporter Michael S. Lockett at 757-621-1197 or mlockett@thedailyworld.com.