Vladimir Shepsis spent his near 50-year career watching ocean waves bash the coast. He witnessed their destructive force on ports and jetties, and developed ways to shield important shoreline infrastructure from erosion.

He now wants to use his ocean expertise, and his knowledge of waves, to capture their persistent power and bring it to shore.

“The waves are very angry and violent at the shore,” Shepsis said. “I came to a conclusion through my life: If you want to take wave energy you need to stay away from the shoreline.”

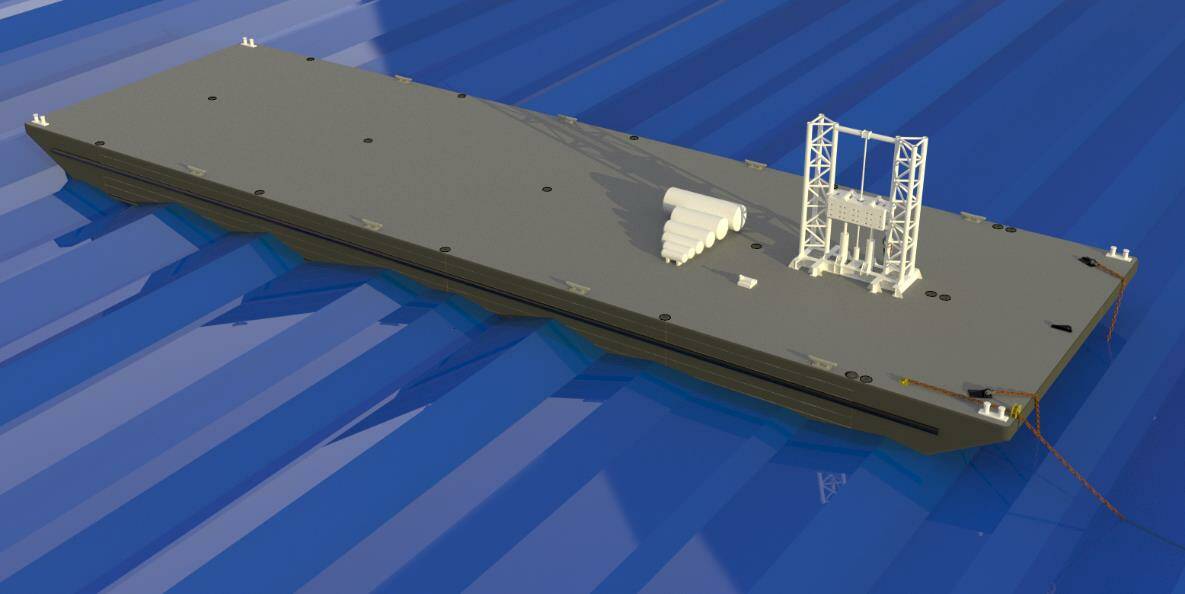

His proposed wave energy hydrogen project would float on a barge five miles out from the coast of Westport, safe from weathering waves but still swaying in — and converting clean energy from — the motion of their troughs and crests.

Shepsis, founder of the one-man Applied Ocean Energy Corporation, presented to commissioners of the Port of Grays Harbor at a Tuesday meeting the final technical report for his ocean wave energy technology.

Shepsis is seeking funding to conduct a six-month, $5.8 million demonstration project that would provide an accurate estimate of the cost to produce barge-hosted, wave-derived hydrogen energy on a commercial scale.

According to Shepsis, extensive testing completed in the last few years has confirmed the feasibility of his technology.

In his model, a 180-foot long floating ship would host four interconnected components: a wave energy converter, which turns the kinetic motion of a pendulum, moved by waves, into electricity; an electric generator; an electrolyzer, which splits the hydrogen and oxygen into elemental form; and storage tanks to hold the elements in liquid or gas form until they can be shipped to shore. The wave converter is the only novel technology in Shepsis’ design.

When hydrogen is consumed in a fuel cell, the only byproduct is water, and it can be used to power cars, homes and industry.

Washington State demonstrated its effort to become a national center for hydrogen production and distribution earlier this year when, as part of the Pacific Northwest Hydrogen Association, it submitted an application for funding to the U.S. Department of Energy’s hydrogen hub program, which could provide up to $1 billion for a hydrogen center in Washington.

Shepsis’ pursuit of hydrogen production began before the state’s push to become a hub. He said his son, a chemical engineer, began working on producing hydrogen from wave energy about 15 years ago.

After partnering on various engineering projects, Shepsis approached the port in 2016 with new ways to convert wave energy, but without the means, as a private entity, to secure the funding he needed for design and engineering. On Shepsis’ behalf, the port helped write an application to secure more than half a million dollars from the state Legislature for the first phases of the project.

“With the emphasis on emerging technologies and green energy, on a scale that might be more appropriate for medium and smaller ports, we felt that we really wanted to help facilitate getting the answers to this,” said Randy Lewis, environmental director with the Port of Grays Harbor.

Lewis said the port’s interest is focused on getting answers about wave energy, and is not involved directly with the project at this point.

Shepsis assembled a team across multiple disciplines: mechanical, marine and electrical engineers, plus hydrogen and renewable energy experts from the Pacific Northwest, and one from Italy.

They went to Oregon State University’s wave research laboratory in Corvallis, and set a small, bobbing prototype — about the size of a coffee table — in the facility’s large wave basin lined in sensors and gauges. Tests showed the model is efficient — the pendulum on the wave converter moved with a greater oscillation than the wave itself.

The wave lab is not OSU’s most ambitious wave energy research initiative. The university is currently constructing the first utility-scale, grid-connected wave energy test site, called PacWave South about seven miles off the Oregon coast. Cables anchored to the seafloor and buried in the shoreline will give developers the chance to easily try out new technologies.

In general, utility-scale ocean wave energy technologies are about 10-15 years behind offshore wind technologies, said Brian Polagye, a professor and renewable ocean energy researcher at the University of Washington. Several leases for commercial offshore wind farms are under consideration on the West Coast, including two in Washington.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management is the federal agency responsible for regulating energy projects on the U.S. outer continental shelf. The PacWave facility became the only permitted wave energy project in the country when BOEM awarded it a lease in 2021.

But Shepsis’ plans are distinct from PacWave because his technology is off-grid, meaning it wouldn’t feed major utility lines and wouldn’t be bound to cables on the seafloor or the shoreline.

For that reason, the demonstration project likely wouldn’t require a lease from BOEM, according to John Romero, public affairs officer with the agency.

And since the barge isn’t tied to the ocean floor, it could deliver energy up and down the coast, sometimes in places hard to reach via automobile, like Alaska, Shepsis said, noting that transporting hydrogen is much cheaper with a ship than with a semi-truck.

Uncertainties about the cost of barge-hosted wave energy at a larger scale have created a Catch 22 for Shepsis: he needs nearly $6 million dollars to carry out the demonstration project for the purpose of estimating costs, but potential funders and investors want to know cost estimates before granting money for the demonstration.

“I am an engineer and I hate to speculate,” Shepsis said. “All my life, I never speculate. I know that the cost is very uncertain right now.”

Even if he doesn’t get the money for the demonstration project, Shepsis said he’s happy to have completed the comprehensive final report — information that could be used to produce clean energy even after he’s gone.

“I strongly believe that five, 10, 20 years from now we will be looking for something in addition to wind and solar. I hope that this time if people come back, they will find all this additional information and it will save them a lot of time and money.”

Contact reporter Clayton Franke at 406-552-3917 or clayton.franke@thedailyworld.com.