Last year, a group of Lincoln Elementary fifth graders induced Grays Harbor County Commissioners to declare a Sasquatch refuge and protection area in the county, presenting that, should the elusive biped exist, the hairy creature is at risk of extinction given the rarity of interactions with humans.

This year, they’ve done it again.

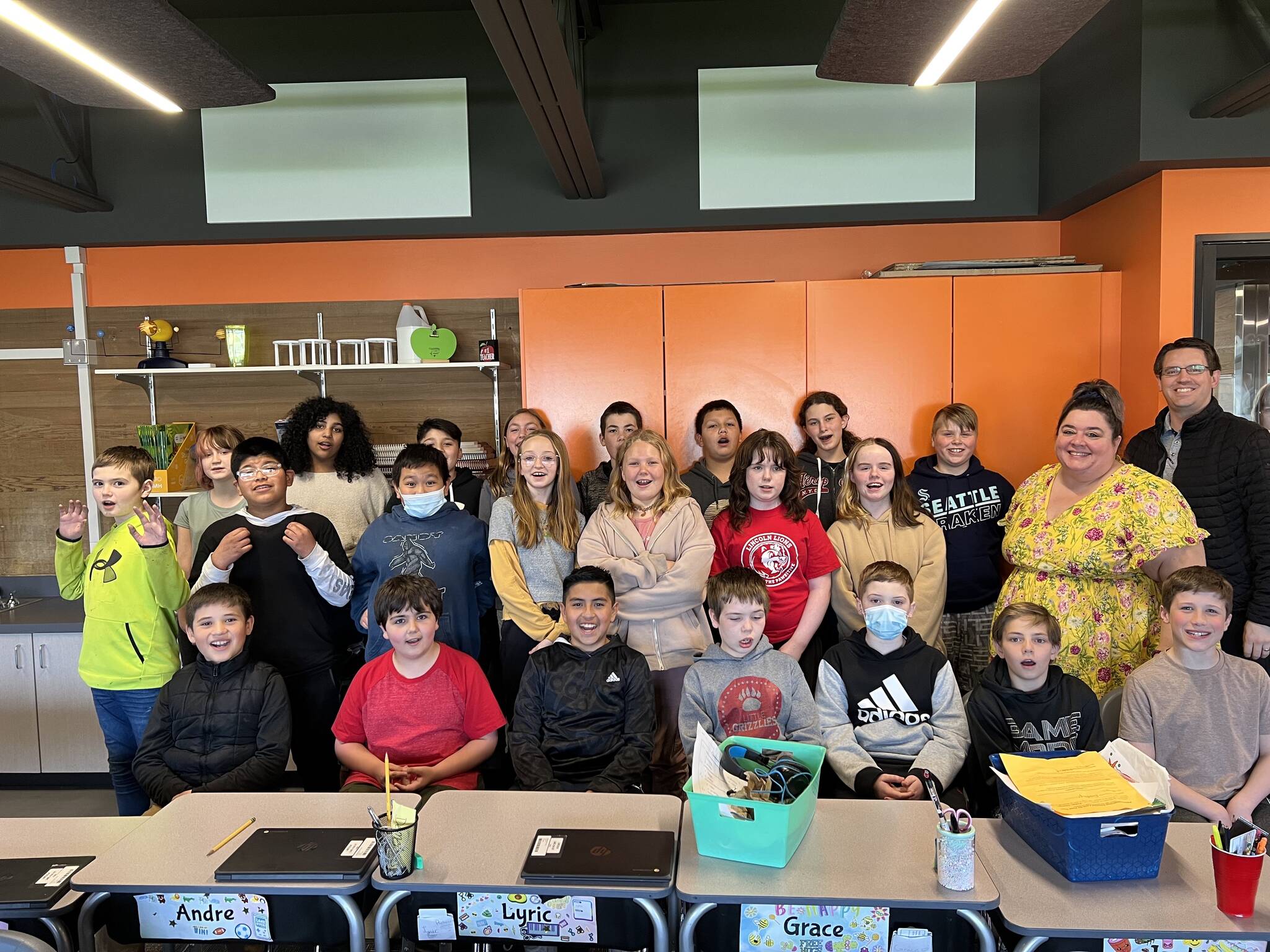

On April 11, about two dozen students gathered and sat on the floor of Andrea Andrews’ classroom, school and district administrators seated behind them. Before them on a large video screen was Clallam County’s primary lawmaking body, its board of commissioners. The students watched as commissioners approved a proclamation to honor and protect Sasquatch — one recommended by the class in a letter to commissioners a few weeks earlier.

“It feels amazing,” fifth grader Jonathan Kelley said later. “Everyone here was able to actually do something to help the entire county.”

Clallam’s proclamation also acknowledges the county’s support of Forks Sasquatch Day, a Bigfoot festival returning for its second year on May 26-28. Before reading the proclamation at the meeting, Clallam County Commissioner Randy Johnson addressed the class.

“I think all the county commissioners were impressed by your letter,” Johnson said. “All of us have a chance to make a difference in the legislative process, which we’re participating in. That could be at the county level, at the city level, at the school board level, at the PTA level. Whatever it is, your voice can be heard if you put it forward.”

Getting students involved with civics — a subject many curriculums no longer emphasize — was a primary reason Andrews drummed up the lesson she calls “Saving Sasquatch,” which Lincoln Principal Kent Nixon called “a beautiful combination of language arts, science and civics.”

It works like this: through research, classroom conversations and a persuasive essay, students make their case for whether or not Bigfoot deserves government recognition. It’s not until they’ve hashed out facts and implications of protecting the cryptid creature that they take the matter to the powers that be.

“People had a lot of different ideas, and so we ended up making three different letters and combining the contents of each of those,” Kelley said.

Unlike last year’s largely-divided class, students this year were overwhelmingly in favor of Bigfoot protections, Andrews said. Their letter to the county commissioners said the loss of Bigfoot — likely an apex predator, should it exist — could result in ecosystem disruptions and “cause issues in the food chain and the human lifecycle,” the letter states.

“If Bigfoot was a real thing, with how much it eats, because it’s pretty tall, it would eat fish, or something in the forest, like cougars,” said student Ashlynn Bale.

Other student research dove into comparisons between Bigfoot and Gigantopithecus, a prehistoric 10-foot-tall ape that went extinct 100,000 years ago. The student letter said Bigfoot protections allow for greater scientific exploration into evidence of the creature around the world.

The students also said there are an average of 49 Bigfoot sightings a year, and many shared experiences — from tall shapes moving in the woods to loud shrieks and knocks — they believe could have been Sasquatch-related.

But anecdotal evidence wasn’t enough for Kruz Callaway, one of two dissenters to the proclamation, who said Bigfoot laws were unnecessary because there is no definitive proof the animal actually exists. Callaway’s willingness to stand up for his position in the Sasquatch debate brought praise from his principal.

“I was really proud of them for standing strong with what they believed and not letting the general masses sway them away from their stance,” Nixon said.

With the signing of Clallam County’s proclamation, there are now four Washington counties with some kind of Bigfoot related law: Grays Harbor, which supported the Lincoln students last year; Skamania, which adopted an ordinance protecting Sasquatch in 1969; and Whatcom, which did the same in 1991. A 2018 bill in the Washington state Legislature proposed to designate Sasquatch as the official state cryptid but was never passed.

Andrews said she plans to continue the Saving Sasquatch lesson. That will require choosing a new Washington county for the students to send their letter next year.

Student Eli Jones has bigger aspirations — he wants to send a Sasquatch protection letter to President Joe Biden.

“It’s more than just Washington,” Jones said. “Down in Florida, they have a lot, too.”

Contact reporter Clayton Franke at 406-552-3917 or clayton.franke@thedailyworld.com.