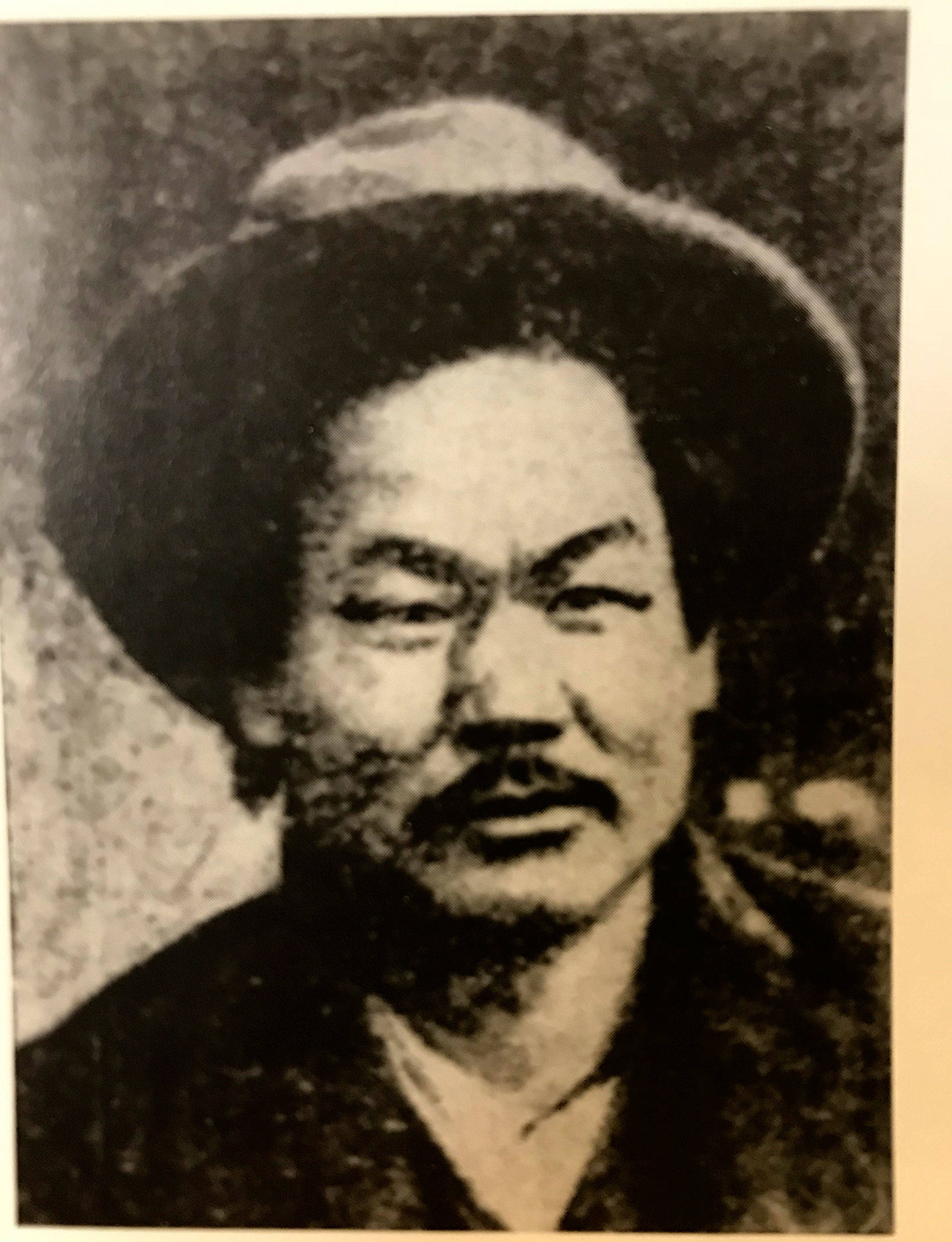

The story of Lum You, a Chinese man who was hanged in Pacific County in 1902 after killing a white man who robbed and harassed him, has been a particularly infamous aspect of local history.

It’s the only official execution ever held in the county, and despite how much attention the story received, a few mysteries in the full account remain to this day, including where You was buried.

To fix this, a Willapa-area woman who dedicates her spare time to locating missing gravesites is working to find a definitive answer to the question of where the executed man was buried. Deborah Sturgill, a former nurse, spends much of her free time researching missing grave sites, scavenging through genealogy websites and county records hoping she can provide a better idea of where people were buried long ago or put a name to unmarked headstones. She then records the findings on Find A Grave, an online grave records database open to the public. She said there have been “hundreds” of grave records she’s posted over the years.

The location of Lum You’s missing grave is one case she’s been working on recently. Sturgill views You’s hanging as a tragic incident, one that was unnecessary and, she believes, influenced by the fact that he was Chinese.

“I like to right wrongs. A lot of cemeteries, where people go on to find a grave, and they’re looking for relatives, sometimes they’re looking from other states, sometimes other countries,” said Sturgill of why she puts in so much time to record grave data. She’s said that for locations “within 100 miles of me, I will go and try to get photos of their ancestors’ graves and whatever I can do, sometimes physically dig for a headstone, and usually I find them. It’s the least I can do.”

A couple weeks ago, Sturgill learned that the site may actually be in a different place than the Pacific County Historical Society’s records show. Sturgill’s goal is to nail down the location of the grave and make a memorial to You, which would likely involve making a trail to the site and placing a headstone. She added that she takes issue with the fact You’s burial site was not memorialized while the grassy site of the old courthouse in South Bend is still called “Hangman’s Park” in reference to the execution.

“(The county) should try and make amends of some sort, I would think, to what they had done wrong historically,” said Sturgill. “I have a problem with Hangman’s Park, it’s like we’re glorifying (that) he was hung there, it’s not done as a memory to him.”

Getting a clear picture of You’s life and death is challenging with the limited records, but there are some. Articles written by the Pacific County’s Historical Society describe You as a well-liked, hardworking man, who was working in canneries near the time of his death, serving as a translator between Chinese workers and white employers.

The following is mostly attributed to the historical society’s account and the grandson of the deputy sheriff at the time of the hanging.

Pacific County’s lone hanging

Prior to the killing You was convicted for, he had another incident in 1894. with another Chinese person who You had grievances against, according to the historical society’s 1971 article that draws from accounts of people who were alive at the time. You went to South Bend’s police chief, who allegedly advised You to kill the man when asked for advice.

“Don’t come to me with your Chinaman troubles,” the chief told You, according to the account. You then asked what he should do to protect himself. “I don’t care. Chop off his head if you want to.”

With the killing incident in 1901, Oscar Bloom, who’s described as a large white man, had been harassing You the night of the murder, according to accounts. Witnesses said they saw Bloom grab You around the neck and steal his valuables and $40.75 in gold and silver coins, and threaten You’s life.

You then retrieved his gun and shot Bloom. Though most people were sympathetic to You, his employers insisted action be taken against him. He was charged with murder and a trial was held in which the jurors voted 11 to 1 in favor of acquitting You of his crime. The story goes that because the one man who voted to indict him held out and would not be persuaded to change, the 11 other jurors “weary with arguing,” voted to convict him. The 11 jurors thought he would receive a lighter penalty than death, and some were shocked hearing the decree he be “hanged by the neck until dead.”

Some recall that You’s cell door was never locked at night, and that he was “encouraged, even ordered, to flee.”

The Sheriff Thomas Roney had invitation cards printed for the hanging, which was held at the county courthouse. Nowadays, the courthouse is gone, but the empty park is still referred to as “Hangman’s Park” because of the event.

Shortly after the hanging, all executions in the state got moved to Walla Walla, making You the only person publicly executed in this way in the county’s history.

For Sturgill and some current members of the historical society, they feel You’s being Chinese played a factor in the hanging. Don Corcoran, 81, is a neighbor to the property that’s listed in the Pacific County Historical Society’s grave records as where You is buried. He agreed with Sturgill saying that race played a factor.

“I’m sure if he were a white guy they wouldn’t have done it,” said Corcoran.

The missing grave site

No one else offered a site to bury You, so the deputy sheriff, Zack Brown, offered his property, but there’s some disagreement in where that exactly was.

Although the historical society’s record says You was buried on what is now a logging road between Raymond and South Bend, the grandson of Brown, Del Brown, says that’s actually his other grandparent’s property.

Del, 92, said the property and burial was actually down a long wooded road at the end of East Second Street, across a bridge that today is dilapidated and only usable on foot. Del would visit the site a few times with his family, and remembers there being an iron fence around the grave site, next to a meadow where cattle grazed.

In stories from his dad, Del said that Chinese people who knew You would sometimes visit the grave to perform ceremonies, and that his dad’s family would sometimes go down to see if there was any food left worth taking.

“When my dad was a young guy, he said they used to see people come and leave food on his grave,” said Del. “They would lay on the hill before going down to see if there was anything left good to eat.”

There’s no remnants of the metal fencing at either the grave site Del recalls, or the logging road in the historical society’s records. However, there is a cleared area next to the path that appeared feasible to bury a body in, and a small piece of ceramic was found in that location.

In the other site on the logging road, Corcoran, said some of his friends recall going to the site as kids to try and find the body.

“Some guys older than me who knew about it said, ‘Yeah when we were kids, we went up there with a shovel to dig him up. We took about three scoops and that was the end of that,’” said Corcoran.

For Sturgill, her next step is to have Del Brown and Corcoran meet to confirm where the grave is located, before getting the memorial built. Some local AmeriCorps members have helped her with similar projects in the past, and said they would be interested in working on this project. Sturgill said if she does find out for certain where it is, she would contact the property owner to get a trail and memorial added.

There is a law that says ”if someone’s buried you have to give access,” said Sturgill. “I’ll push it that far, a trail isn’t going to kill anyone.”