NEAH BAY — The next generation of ocean research was on bright display in Neah Bay this week.

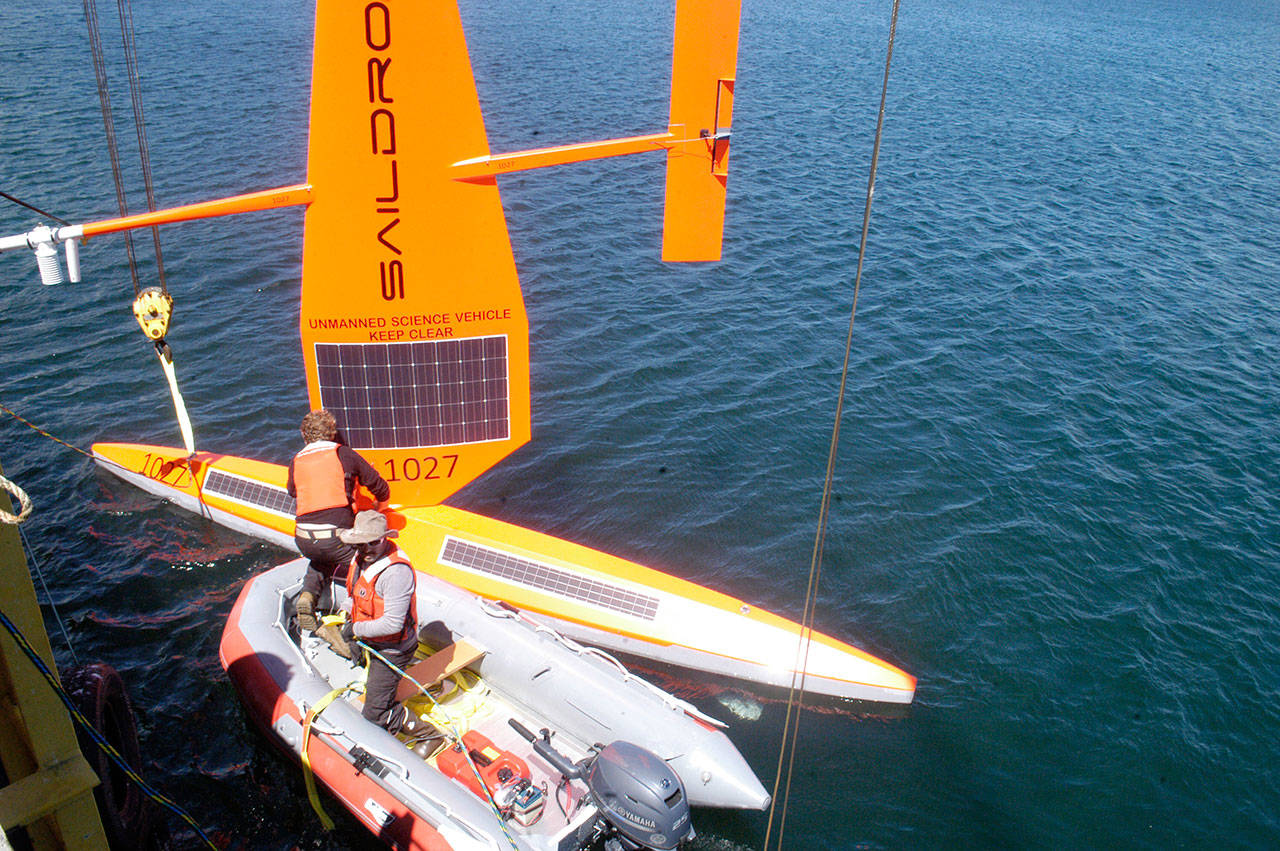

Two orange unmanned sailing drones, created by Saildrone Inc. of Alameda, Calif., were launched from the Makah Tribe’s commercial fishing dock Tuesday to begin a three-month test of their efficiency and accuracy in assessing fish stocks up and down the West Coast.

Saildrones 1027 and 1028 will use solar-powered instruments to collect and send acoustic data on Pacific hake and other fish species from the northern tip of Vancouver Island to California.

They will join two other drones that were launched from San Francisco Bay to supplement the scientific work of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) ship Reuben Lasker crew.

A fifth Saildrone will be deployed in August to assess pelagic fish like sardines and anchovy closer to shore.

NOAA officials say the autonomous vehicles will enhance future stock assessments, which are used by the Pacific Fishery Management Council for setting quotas.

“We are thrilled to be here launching this survey,” said Nora Cohen, business development lead for the company, at a sun-splashed ceremony on the Makah pier. “It’s the first of its kind.”

The 2018 West Coast fisheries mission was launched by NOAA Fisheries, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Saildrone Inc.

Ruth Howell, communications manager at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center, said Saildrones have the potential to “expand the efficiency, precision and accuracy of the science work that we do.

“This is the first time that we’re sending out these drones for the West Coast,” Howell said during an informal press conference between the two launches.

“This is building on several years of work and partnership between NOAA and Saildrone to explore how we can augment our existing science mission, to understand oceans and atmospheres, to gather information about fisheries and to feed into our stock assessments.”

Saildrones rely on wind for propulsion and have solar-powered sensors that can provide data on fish biomass and oceanic and atmospheric conditions in real time.

The high-tech drones have been used to measure fish populations for three years in the Bering Sea and are now being used to study the oceans of the Southern Hemisphere and tropical Pacific.

“It’s beyond proof of concept, because they’ve already used it to measure fish populations in other areas,” Howell said in a later interview.

“But it’s the first time that it’s applied on the West Coast, and the first time that they’re calibrating it with our existing platforms.”

Since they require no fuel, Saildrones can spend up to a year at sea.

“We’re able to go places where you don’t really want to send people, go places that are too far to send people and go into weather that you really don’t want to have anyone, ever, be in,” Cohen said, “and be able to send back measurements in real time.”

Saildrone Inc. rents the autonomous vehicles to partners like NOAA at a cost of $2,500 per day.

The Saildrones were designed by company founder and CEO Richard Jenkins, who coordinated the launch in Neah Bay.

Jenkins developed the technology as part of his 10-year effort to break the land wind sailing record, which he accomplished in 2009 by reaching 126.2 mph in the Mojave Desert.

Chris Meinig, director of engineering at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Lab, worked with Jenkins to develop the public-private partnership, Cohen said.

In addition to stock assessments, Meinig said Saildrones could be used to detect marine mammals or to sample surface water for harmful algal blooms.

“There’s a whole array of places we want to go, but I’m really excited that the technology is at this level now that we’re expanding it out to the West Coast,” Meinig said.

During the West Coast survey, Saildrone will send four other vehicles to Dutch Harbor, Alaska, to study fish and two more to the tropical Pacific to work on El Nino predictions, Cohen said.

“We will be expanding to a lot of other places, I expect, in the next year to two years,” Cohen said.

Stephane Gauthier, a research scientist with Fisheries and Oceans Canada, said the autonomous vehicles will “fill in some of the temporal and spacial gaps” in existing fish surveys.

“It’s expensive, and it takes a lot of human resource, to do those surveys on board large vessels,” Gauthier said.

While Saildrones can provide much-needed data, autonomous vehicles will never replace the large NOAA research vessels, Howell said.

“There are reasons that we need to get out on vessels — to be able to validate what we’re seeing,” Howell said.

Saildrones 1027 and 1028 were scheduled to rendezvous with the Reuben Lasker at the northern tip of Vancouver Island and begin a series of transects across the continental shelf that runs perpendicular to the shore.

The transects will begin in Canada and end at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“We call it mowing the lawn,” Gauthier said.

Multiple Saildrones will be used for each pass that the Reuben Lasker makes.

NOAA research vessels cruise at about 12 knots. Saildrones travel between 3 and 8 knots when the wind is blowing.

“They can keep a heading irrespective of the wind direction,” Gauthier said. “Even when wind is head-on, they can go forward because of the design. But they still need the wind.”

The Pacific hake fishery, one of the largest on the West Coast, is jointly managed by the United States and Canada.

“There’s a lot of questions surrounding our surveys and our assessment just because we can’t be out there all the time everywhere,” Gauthier said.

“So having a fleet of Saildrones like this could really improve the gaps.”

The U.S. hake fishery contributed more than $46 million to West Coast ports like Westport and Astoria, Ore. in 2016, NOAA officials said.

Gauthier predicted that data from Saildrones would be used for fishing quotas “a few years” into the future.

By that time, Saildrone officials hope to have 1,000 autonomous vehicles taking scientific measurements around the world.

“We’re building them fast,” Cohen said.