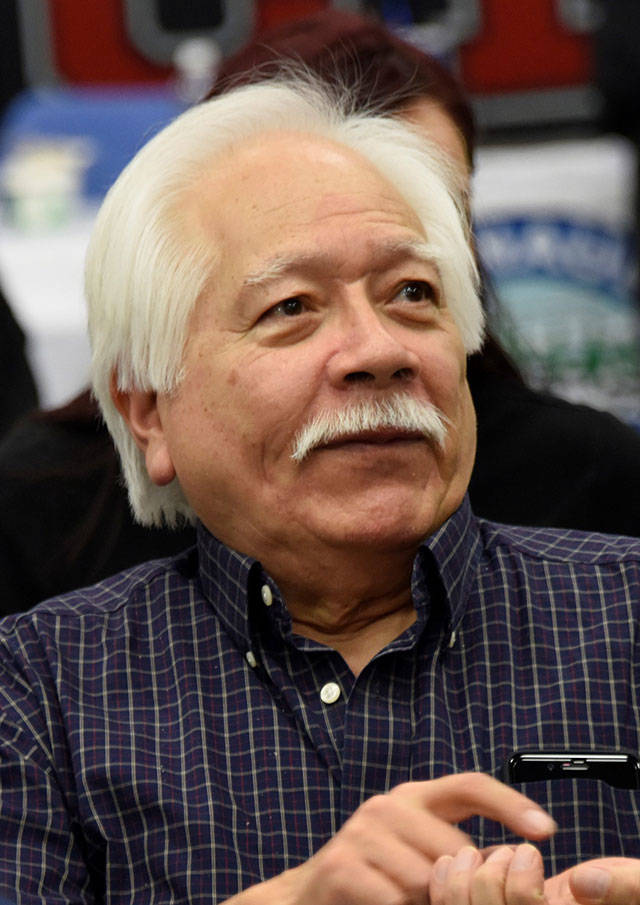

Jim Harp, ancestral member of the Shale Clan of the Queets Band of the Quinault Indian Nation, passed away from brain cancer at his home on Nov. 28, 2018, in Montesano, Washington, at the age of 73. Born in Aberdeen, Washington, on June 27, 1945, to Hilda Shale and Edward Harp, he grew up learning to fish at an early age, from his grandfather Howard and his grandmother Flora Logan.

After being drafted into the Army during the Vietnam War, Jim was stationed at Fort Ord, underwent training at Fort Bliss, and served in Germany as a Nike-Hercules Guided Missile electronic technician until he was discharged in 1968. After working for a short time with the Boeing Company, he returned home to fish where the Queets River entered the Pacific Ocean on the Quinault Indian Reservation. There he married his lifelong partner, Karen Sotomish, and became a councilman on the Quinault Business Committee, a position he would ultimately hold for 25 years.

He was able to fish peacefully until Judge Boldt issued his decision in the Indian treaty fishing rights decision, United States v. Washington in February of 1974. The public and political uproar that resulted from the affirmation that signatory tribes to Indian treaties signed with the United States in the 1850s reserved the right to take 50% of the harvestable fish at their usual and accustomed fishing places off reservation, would change his life forever.

Even though the “Boldt Decision” did not involve fishing on Reservation, Jim found himself suddenly confronted with threats to his ability to practice his craft of fishing to feed his family and earn a livelihood. The Washington Departments of Fisheries and Game attempted to impose their will on tribal fisheries on the Queets River. Unfamiliar, confusing, and frustrating legal processes like Fisheries Advisory Board sessions, protests from non-Indian commercial and sports fishermen, violence on the water, and protracted litigation arose all too often. Because of the growing threat to Quinault Treaty fishing rights, three Quinault leaders, Joe DeLaCruz, Jim Jackson, and Oliver Mason decided that Jim was the one to call upon to protect and advance the interests of the Quinault Nation. He was given two Indian names. One “Peacemaker”, was conveyed with a sense of gravity and responsibility and a message “You’re going to earn it.” The other was “One who calls fish”, reflecting the duty of stewardship for the resources that had sustained Indian ways of life for countless generations. He also had a respect for the eagles, deer, bear, and other creatures that shared the earth, air, and its waters.

At the time, Jim didn’t know a lot of the technical details of salmon biology or fisheries management, but he was a lifelong learner and quickly turned his attention to understanding about the resource and approaches to harvest management. He devoted himself to do something to improve management of fisheries resources for the benefit of tribal and non-tribal peoples. During the course of his career, became the Assistant Director and Fisheries Manager for the Quinault Nation for nearly 20 years, served on the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission for 20 years. He worked tirelessly on behalf of all tribal peoples, not just Quinaults.

Professionally, careful attention to detail, unflinching demand for accuracy, amazing memory, and preparation were widely admired. These qualities made him a natural mentor for a new generation of fishery biologists and scientists over the years. On a personal level, his humanity, care and respect for others were recognized and cherished.

As he learned his way, Jim quickly rose to positions of leadership and responsibility. He served as the Vice Chairman of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission, working with Billy Frank Jr., WDF Director Bill Wilkerson, and others to find a way to move from confrontation to co-management. He was a member of the Pacific Fishery Management Council for 18 years, chaired its Budget Committee, and was a principal force behind the creation of the collaborative “North of Falcon” planning process. He became vice-chairman for the Klamath Fishery Management Council, a member of the Southern Panel of the Pacific Salmon Commission until 2010, and a member of Governor Booth Gardner’s Salmon Advisory Committee. After dedicating much of his life to fish and fishing, Jim went on to chair the Quinault Allottees Association taking up issues relating to land and forest management.

His efforts to provide fishing opportunities for tribal peoples extended beyond salmon to clams, crab, halibut, sablefish and all other species within their usual and accustomed fishing places. Jim wasn’t just a simple fishermen from Queets, he had a presence and impact that changed the face of fisheries management. He touched and was touched by many. He will be missed.

“I walk on proud with my head held high.”

Jim Harp November 2018

Jim is survived by his wife Karen and a step daughter, Linda Colleen Reeves of Pacific Beach, a sister Lydia Shale from Queets, his cousin, Florine Shale-Bergstrom from Aberdeen, his sister-in-law, Sarah Colleen Sotomish and his niece and nephew Melanie and David Montgomery of Olympia, and many nieces and nephews.

A funeral service for friends and family was held at Coleman Mortuary in Hoquiam on Dec. 5, officiated by Rose Davis, Minister, Mud Bay Shaker Church, followed by interment at Sunset Park Cemetery, and a memorial dinner at the Aberdeen Log Pavilion.

Jim’s family expresses great admiration and appreciation for the care provided by his doctors as he struggled to battle the debilitating effects of his cancer. Memorial donations to a cancer charity of choice are suggested in honor of Jim’s passing.

Please take a few moments to record your thoughts for the family by signing the on-line register at www.colemanmortuary.net.