By Sharese King and Katherine D. Kinzler

Los Angeles Times

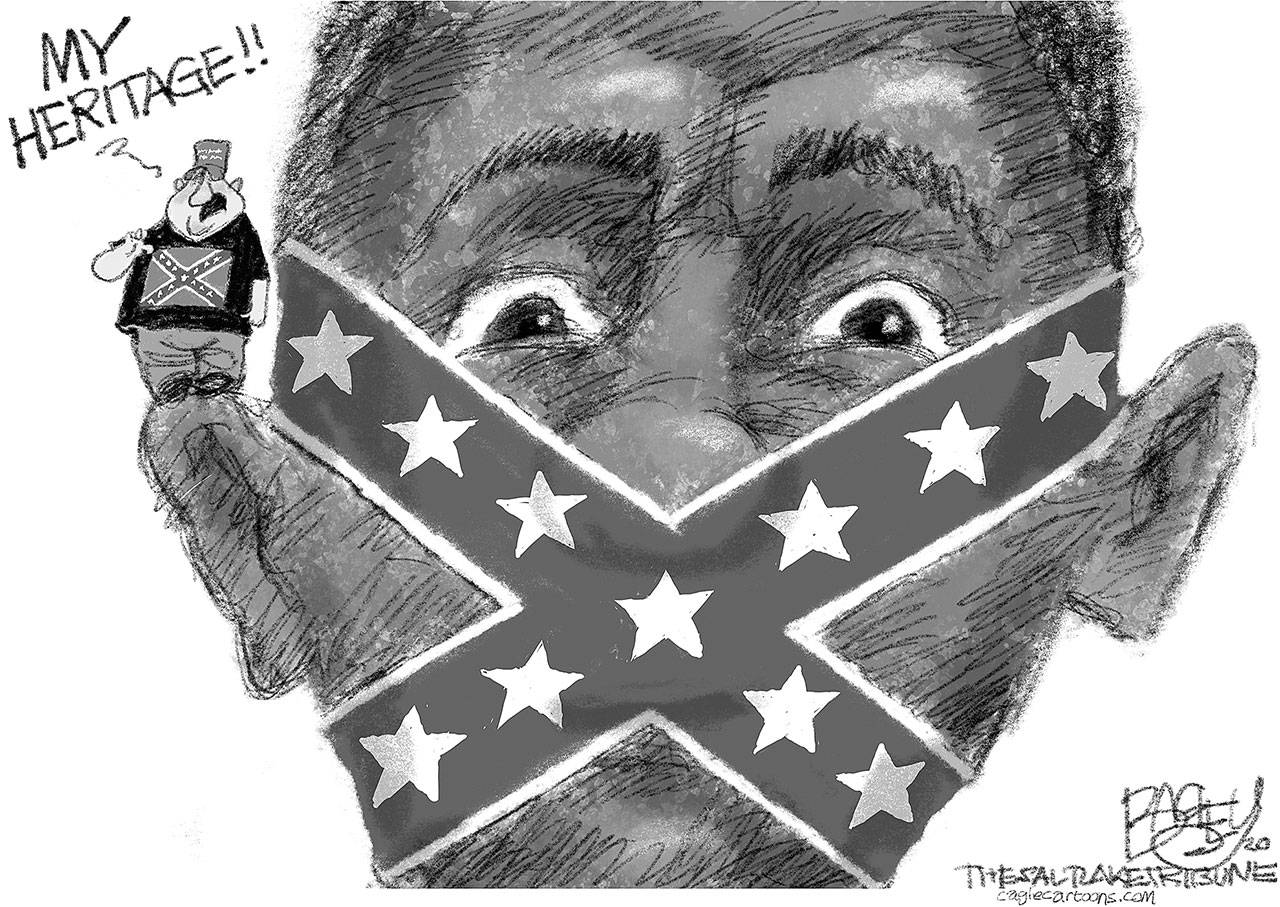

In the national conversation taking place about systemic racism in the United States, one important element should not be overlooked: linguistic prejudice.

African American English, like other dialects used in the U.S., is a legitimate form of speech with a deep history and culture. Yet centuries of bias against speakers of AAE continue to have profound effects on employment, education, the criminal system and social mobility. To attack systemic racism, we have to confront this prejudice.

Of course, some of the greatest examples of American oratory and literature have roots in AAE, also known as African American Vernacular English. The works of Zora Neale Hurston and Toni Morrison are infused with AAE. Its significance cannot be understated when examining the speeches of orators like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and President Barack Obama. In American music, it has moved beyond African American communities to influence all genres, from blues to hip-hop.

None of this, however, has prevented the dialect from being used to justify the marginalization of its speakers.

The history of AAE, spoken by many Black Americans, is complex. Some linguists suggest that the dialect has roots in West African languages and shows striking parallels with Caribbean Creoles. Others argue that older varieties of AAE resemble the English dialects spoken by white indentured servants who lived in close proximity with enslaved people. Some of the modern features of AAE overlap with aspects of Southern dialects, carried by African Americans in the Great Migration from Southern rural communities to Northern urban areas.

Like any dialect, AAE is a part of the cultural fabric of its speakers and has its own accent and rule-governed grammar. But despite its legacy in shaping American culture, this historic language is often derided as ungrammatical and linguistically less than other forms of American speech. The result is that AAE speakers are denigrated and discredited based on their speech.

To give one tragic example, linguistic prejudice undermined the credibility of a key witness in the trial of George Zimmerman for the murder of Trayvon Martin, an African American teenager, who was unarmed when he was shot by Zimmerman while walking near his relatives’ home in their gated community in Florida.

In the moments before his death, Martin was talking on his cellphone with his friend Rachel Jeantel. Jeantel described at trial how she heard Martin trying to get away from Zimmerman, not assault him. Her testimony should have made her the prosecution’s star witness, casting doubt on Zimmerman’s claims of self-defense. Yet, because she spoke in AAE, jurors reported that she was “hard to understand” and “not credible.” A juror later reported that during 16 hours of jury deliberation no one mentioned Jeantel’s testimony at all. Her voice didn’t matter.

Part of the jury’s lack of consideration of Jeantel’s testimony was likely because AAE was unfamiliar to the nearly all-white jury, and therefore harder for them to understand. At the same time, mere “comprehension” is never the full story. Decades of research in psychology and linguistics have shown how feelings of prejudice can determine views about comprehensibility and credibility.

People can shut down and stop trying to understand when they don’t like the dialect of the person speaking. Even when adults are perfectly capable of understanding speech in a nonnative or unfamiliar dialect, they often find the words spoken to be less credible. Facts conveyed in a nonnative accent are heard as less true. Analyses of legal settings around the globe suggest that those who speak stigmatized dialects are often misunderstood, misheard and mistranscribed.

In fact, speech-based prejudice can be an especially insidious form of racism, because people don’t recognize how deeply cultural stereotypes and attitudes inform their views about speech. People may chalk up negative feelings toward a speaker to difficulty of comprehension rather than racial bias. They may think to themselves, “I just don’t understand that person” or “they aren’t speaking clearly” when in fact, racism and linguistic judgments are intertwined.

Beyond the courtroom, prejudice about speech affects people’s housing, employment and educational opportunities, and has particularly negative impacts on Black Americans.

For example, when the linguist John Baugh called hundreds of prospective landlords to ask about the availability of an advertised apartment, he was much more likely to hear “yes” when he purposefully made his voice sound “white” rather than “Black.” In another study, the economist Jeffrey Grogger found that speech patterns are associated with wage inequality, with Black workers who were perceived as sounding Black earning 12% less than similarly qualified whites (this was not the case for Black workers whose race was not distinctly identifiable by their voice). And in education, children who speak AAE may be told that their speech isn’t “proper” or legitimate, while at the same time they may not be given the support they need to master the academic dialect used in schools.

Without recognizing the weight of linguistic prejudice, injustices in many domains of civic life will continue. Anti-racist reforms by institutions and individuals will require thinking about race and speech —and opening our minds to the equal value of speech in all its forms.

Sharese King is an assistant professor of linguistics at the University of Chicago. Katherine D. Kinzler is a professor of psychology at the University of Chicago. She is the author of the forthcoming book “How You Say It: Why You Talk the Way You Do and What It Says About You.” @K—Kinzler