By Rich Lowry

Bernie Sanders may be on the verge of gaining an insurmountable lead in the Democratic nomination fight, but he’s not letting that get in the way of his socialist principles.

Asked in a “60 Minutes” interview about old statements praising Fidel Castro’s supposed achievements in health care and education, Sanders stayed true to himself.

“You know, when Fidel Castro came into office, you know what he did?” he told interviewer Anderson Cooper. “He had a massive literacy program. Is that a bad thing? Even though Fidel Castro did it?”

No, literacy programs aren’t a bad thing, but they usually don’t require seizing power in a violent revolution, jailing and killing political opponents, seizing private property, or outlawing the free press. Teaching children to read is something that happens in free societies, too. That Bernie continues to believe a literacy program is some kind of recommendation for a regime that has otherwise oppressed and immiserated its people for decades is a sign of his skewed view of what’s important and just for a polity.

Asked by Cooper about jailed Cuban dissidents, Sanders said he condemns that, but in any rational view, it’s the imprisoning of people for expressing unwelcome political views that is the foremost thing to know about the Cuban dictatorship, period, full stop.

The left has nonetheless always viewed Fidel Castro as some kind of social worker who happened to take and hold power — or “come to office,” as Sanders delicately puts it — via force.

Back in 1989, Sanders wrote, “Cuba — the one country in the entire region that has no hunger, is educating all of its children and is providing high-quality, free health care — is hated with a passion by the Democrats as much as Republicans.”

Besides the moral obtuseness of arguments like this, the factual basis for such claims is dubious. Cuba was already doing well on measures of health care and education prior to the revolution. By one estimate, Cuba’s per capita income in 1955 was about half that of the most advanced Western countries and on par with Italy’s. By 2000, after the collapse of the Soviet Union that had provided Cuba an economic crutch for so long, Cuba’s per capita income was half what it had been in 1955.

Cuba went from being a leader in Latin America on key economic measures to a laggard by the time Castro was done with it. The Washington Post has noted that “in terms of GDP, capital formation, industrial production and key measures such as cars per person, Cuba plummeted from the top ranks to as low as 20th place.”

Bernie’s perspective on Cuba isn’t an outlier. It is characteristic of his worldview that has a sympathy for America’s enemies, at least if they are communist or Islamist; that assumes the worst of the United States; and that opposes nearly all U.S. military interventions as misbegotten or malign (Sanders voted for the Afghanistan War after Sept. 11, and now regrets even that vote).

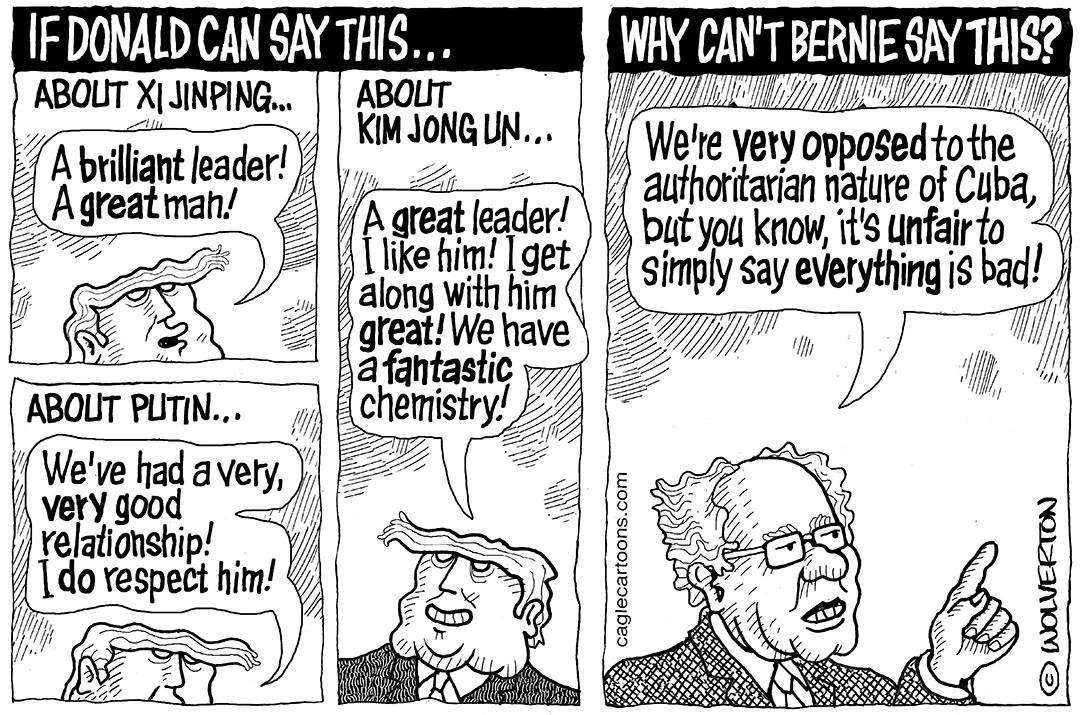

Electing Bernie Sanders would be almost indistinguishable from putting the late radical historian Howard Zinn, or the America-loathing linguist Noam Chomsky, or the tendentious left-wing filmmaker Michael Moore in charge of American foreign policy. The country would be in the hands of an opponent of its power with no faith in its goodness. Bernie would make Barack Obama’s overly solicitous attitude toward our enemies and Donald Trump’s bizarrely warm statements about foriegn dictators look like American foreign-policy orthodoxy by comparison.

There is almost no enemy of the United States that wouldn’t be heartened by a Sanders victory, and see it as an opportunity to make gains at the expense of the United States and its allies. If his decades-long track record is any indication, Sanders would be inclined to make excuses for our adversaries and look on the bright side of their repression and rapine.

He’s doing it with the Cuban dictatorship to this day.

Rich Lowry has been the editor of National Review since 1997. He’s a Fox News political analyst and writes for Politico and Time. He is on Twitter @RichLowry.