By Rich Lowry

It shouldn’t be news that John Bolton can attest to a White House scheme to pressure Ukraine on investigations.

The existence of this campaign, now at the center of the impeachment fight, has been obvious for months. There is no mystery here, no whodunit, no dining-car reckoning from “Murder on the Orient Express” or bank-vault confrontation from “The Red-Headed League.” No more sleuthing is necessary.

A quid pro quo was suggested, if not proven, by the transcript of the White House call between Donald Trump and his Ukrainian counterpart Volodymyr Zelenskiy. It was hinted at by the unexplained hold on Ukrainian defense aid. It became clearer in texts among Trump officials involved in Ukraine policy about securing a public commitment to investigations. It was made even more evident in the testimony of European Union ambassador Gordon Sondland that realizing what was happening was a matter of 2 + 2 = 4.

If there wasn’t any pressure on Ukraine on investigations, it’s inexplicable why so many U.S. officials acted as if there were and why Zelenskiy was on the verge of making a statement about investigations, despite Kiev’s misgivings.

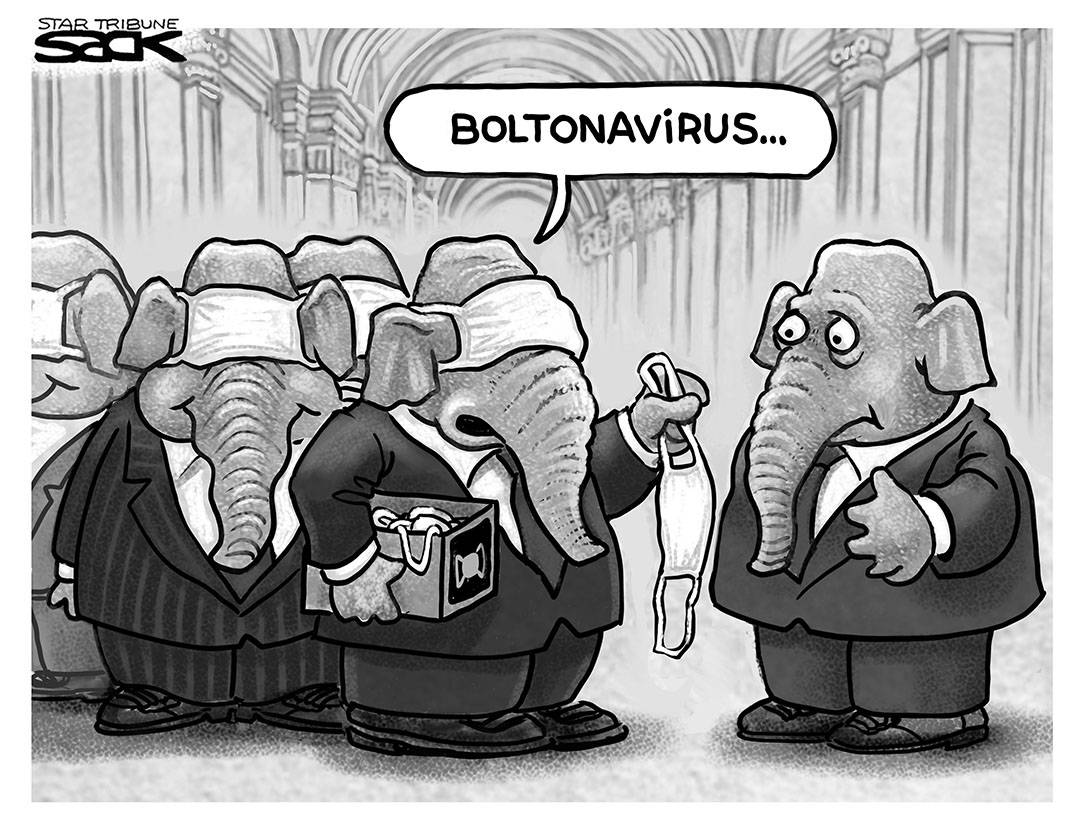

All of this means that former national security adviser John Bolton’s book, reportedly setting out how President Trump pushed for the investigations, is best understood as another piece in a well-established tapestry rather than a game-changer.

That it is being played up by the press as such a bombshell is, in part, an artifact of the decisions of the president and his own team.

In Washington scandals, often what becomes important is determined by what is conceded and not by whomever is being investigated. It determines what the investigators will focus on proving, what will become tests of credibility, what the press will deem especially newsworthy.

In the Ukraine matter, Trump has conceded nothing. He insists that his call with Zelenskiy was “perfect” and that there was “no quid pro quo.” This makes any revelation to the contrary damaging when it rightfully should be considered, in that scandal cliche, old news.

Good defense lawyers would never go down this route of denying the obvious. It is unnecessary to the task at hand of getting an acquittal in the Senate. But the White House team is constrained by Trump’s smash-mouth instinct for total denial and total war, leaving them no option but to contest the underlying facts and complicate their own argument.

It makes no sense to say, on the one hand, that the House impeachment case fails for lack of firsthand witnesses, but, on the other, that there should be no firsthand witnesses. It is malpractice to go out on a limb saying no one has direct knowledge of a quid pro quo, when a witness with direct knowledge, Bolton, is ready and willing to testify. It is foolhardy to make assurances that could easily — and probably would — be contradicted if the Senate did decide to call for any witnesses.

As for the senators, most of them disdain Adam Schiff and what has been an ongoing campaign to destroy the Trump presidency. They have no interest in getting crosswise with the president, or with their own voters. So, they keep to themselves or downplay their belief that we know what Trump did in Ukraine and that it was inappropriate.

The way to make a case against witnesses and to inoculate against what Bolton or anyone else might say is to acknowledge that we know what happened and to maintain that, even if it’s blameworthy, it doesn’t justify removal. This would have the advantage of being true. It would also make the Senate’s role comparable to an appellate court rendering a threshold decision of law rather than a trial court sifting through the evidence.

The Bolton news may force Senate Republicans, and eventually the president’s team, into this posture — after they’ve exhausted the alternatives.

Rich Lowry has been the editor of National Review since 1997. He’s a Fox News political analyst and writes for Politico and Time. He is on Twitter @RichLowry