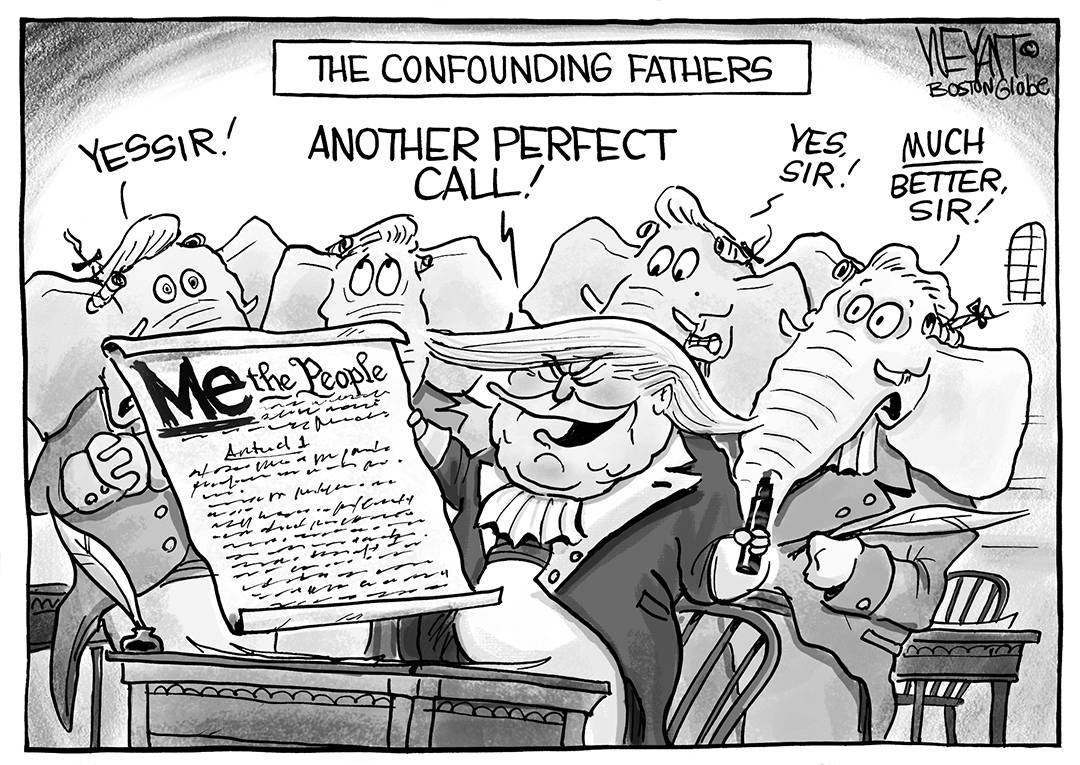

There has been much talk lately among both Democrats and Republicans of the intents of the founders in the writing of the Constitution, especially involving the powers of impeachment and removal from office.

What has been sorely lacking from this conversation is an awareness of the framers’ overwhelming conviction that there was nothing more poisonous to constitutional democracies than demagogues —which to them meant a very specific kind of threat.

Less than two weeks after the start of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, George Washington wrote to his friend, the Marquis de Lafayette, on June 6, 1787, explaining that his critical purpose in attending the convention was to prevent a demagogue from gaining power in the politically unstable young nation and thus destroying it.

Washington described how he was pulled out of retirement by an urgent risk to the United States. “Anarchy and confusion” were threatening the security of the American people and the rule of constitutional law. But this was only half the danger.

The deeper risk, he wrote that early June, was that the political chaos created fertile ground for exploitation “by some aspiring demagogue who will not consult the interest of his country so much as his own ambitious views.”

In a letter written three weeks later to David Stuart, a Virginia politician and distant family relation, Washington lamented that the widespread denigration of the Articles of Confederation, and the federal government it created, had rendered “the situation of this great country weak, inefficient and disgraceful.” He concluded the letter to Stuart by again stating that the political crisis made possible demagogues who pose a dire threat to the United States.

Washington’s greatest fear that summer of decision in Philadelphia was that unwise, self-seeking politicians —even if fairly elected to public office —would tear down the central government and its constitutional laws for the sake of their own advancement and glorification.

Washington, like his peers, did not use the word “demagogue” as an insult or epithet. He did not employ it as ammunition against those he identified as his political opponents. For the steady, rational Washington, “demagogue” was a forensic term that described a well-known class of political actors, known since Greek and Roman times, who obtain power through emotional appeals to prejudice, distrust and fear.

Irrespective of party affiliation, demagogues were a distinct personality type that knew no bounds of politics except fiery self-aggrandizement.

Washington, of course, was not the only framer who viewed our Constitution largely as a bulwark against demagogues. In the surviving records of the speeches given at the Constitutional Convention, the word “demagogue” was used 21 times by the framers as they crafted the Constitution’s essential checks and balances against despotism and tyranny.

“Demagogues are the great pests of our government,” said Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts during the convention, “and have occasioned most of our distresses.”

Gerry further described demagogues as “pretended patriots,” unprincipled politicians who steer the people toward “baneful measures” through “false reports.”

James Madison of Virginia twice alluded to “the danger of demagogues.” Alexander Hamilton of New York spoke of this peril of democracy more than any other delegate, naming it seven times. Demagogues, Hamilton said on the floor of Independence Hall in late June 1787, “hate the controul of the Genl. Government.”

Later, Hamilton went on to predict an ominous decline in republics from demagoguery to tyranny. As he put it in Federalist No. 1: “History will teach us that … of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics, the greatest number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people; commencing demagogues, and ending tyrants.”

Other framers who raised the red flag of demagoguery during the Constitutional Convention were Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania, Pierce Butler of South Carolina and Edmund Randolph and George Mason of Virginia. Mason declared outright that “the mischievous influence of demagogues” was one of the top two “evils” that can befall republican forms of government.

This destructive risk of demagogues is one reason the 55 framers of the Constitution adopted the power of impeachment during the historic convention of 1787.

They believed uniformly that some men, though elected by the people, would be temperamentally incapable of serving the public interest under the Constitution. Therefore, they offered Congress the remedy of impeachment and removal from office.

The framers did not view the exercise of this remedy to be an anti-democratic act of nullifying elections. To the contrary, they provided the people and their representatives with these emergency powers for the specific purpose of rescuing our democracy and Constitution from harm and destruction at the hands of demagogues.

Eli Merritt is a visiting scholar in the department of history at Vanderbilt University. Twitter: @elimerritt