Bruce Yandle

Tribune News Service

As if homebuyers, contractors, and do-it-yourselfers don’t have enough to think about in this summer’s hard-to-read economy, the price of framing lumber has skyrocketed from $600 per thousand board feet to more than $1,400 in the last six months.

Higher cost lumber has added an estimated $36,000 to the average price of a new home. Some may wonder about President Donald Trump’s 2017 decision to impose 20 percent tariffs on Canadian timber products, and we should all question Biden administration threats to reimpose them.

Though softened to 9 percent in the early days of the new administration, the tariffs caused U.S. consumers to bear the brunt of a misguided effort that, oddly enough, put substantial sums in the pockets of Canadian-owned U.S. lumber producers, as well as their U.S.-owned competitors. How all this could make America great again is difficult to imagine.

The Trump decision was extraordinary at the time because it imposed higher tariffs on the products of specific Canadian firms that exported to the United States (while also more typically laying an overall tariff on all producers). U.S. interests favoring the tariffs, which were primarily American-operated Pacific Northwest mills, pointed to Canadian government subsidies which they claimed unfairly assisted Canadian firms to obtain logs from government-owned forest land.

Those who were opposed to the tariffs, like American home builders, argued that the subsidy allegation was hard to prove, and that higher tariffs would surely impose high costs on American consumers.

All of this was in conjunction with failed efforts by trade negotiators to resolve a decades’ long U.S.-Canadian dispute regarding Canada’s tariffs on U.S. dairy products. While the war of words roared away, no one seemed to point to the fact that Canadian-owned U.S. lumber mills would be counted among the big winners in the Make America Great Again trade skirmish. But that’s exactly what happened.

When the COVID pandemic hit and trillions of dollars of federal stimulus funds began making their way into the bank of accounts of hard-hit (and not-so-hard-hit) American consumers, the options for spending money were rather limited. With millions working at home for the first time ever, countless families decided this would be a good time to add a deck, another room, or move up to a new home. Demand for building materials shot skyward as did prices for lumber, steel and copper.

Meanwhile, domestic lumber producers — whether U.S. or Canadian owned — banked substantial profits. In a survey of the top 10 U.S.-based 2020 lumber producers, three were Canadian owned, and their combined volume accounted for more than 30 percent of the total Big 10 production.

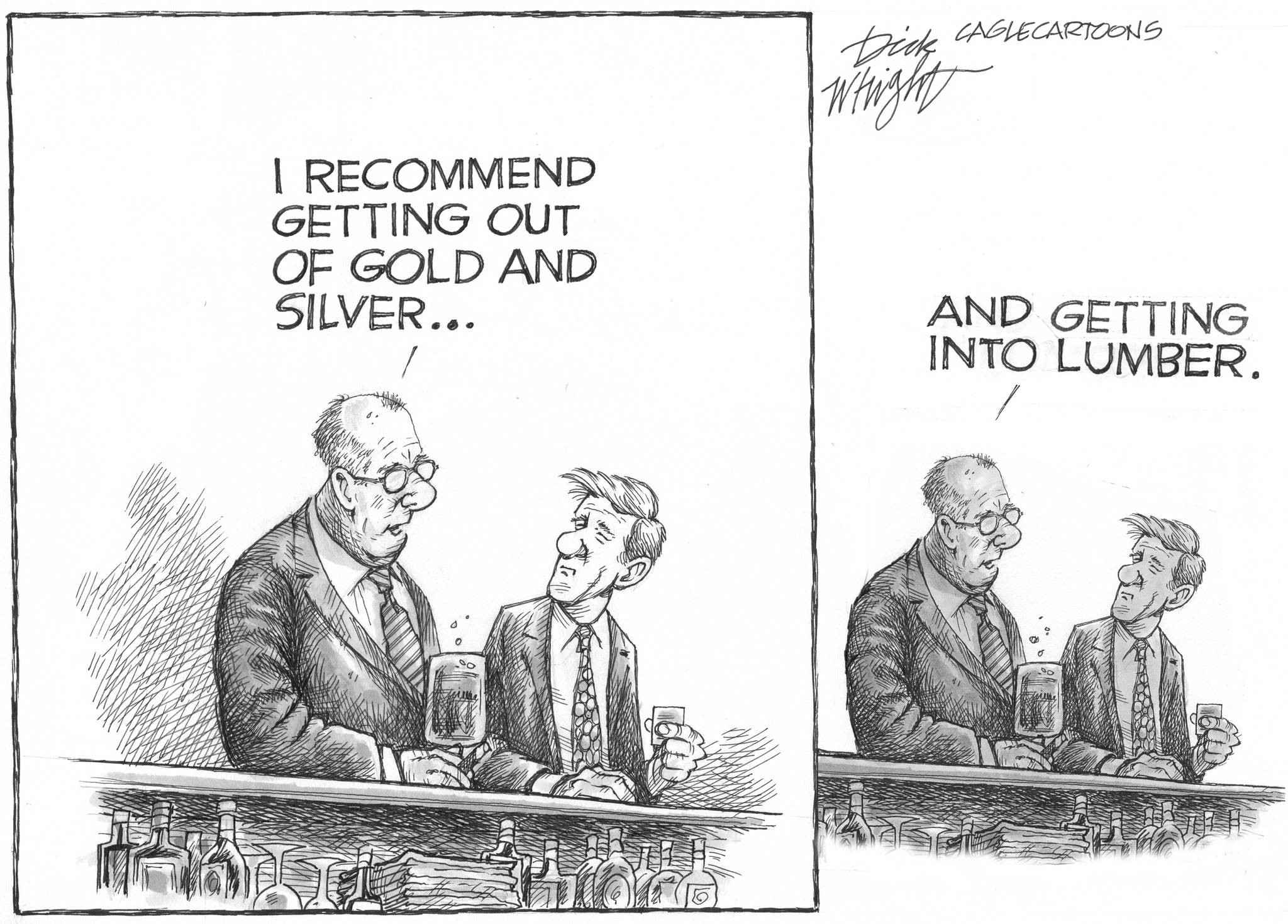

Is there a lesson to be learned here? Most people understand that tariffs leave some winners and some losers. A somewhat-smaller group, which includes most economists who study such things, recognizes that tariffs impose far greater costs on all consumers combined than benefits provided to the interests they protect. This is nothing new. It has been known and commented on for ages. It’s also no secret that politicians respond to organized interests. Consumers — in this case our homebuyers and deck builders — are not especially well-organized.

But there is a harder lesson to heed: No group of Washington’s brightest and best can have enough knowledge to predict what will actually happen — who will benefit and who will pay — when major policy interventions occur. Try as we might, we just can’t get it right. But we can perhaps learn to accept what we don’t know and be more cautious before pulling a tariff trigger.

Even now, the Biden administration is attempting once again to settle the Canadian-U.S. timber controversy, and along with it the dairy products trade problem. And even now, the U.S. trade negotiator is calling for a return to Trump-level lumber tariffs, up from the recently reduced 9 percent level, perhaps as part of a negotiating strategy.

Meanwhile, Canadian owners of U.S. lumber producers smile all the way to the bank.

Bruce Yandle is a distinguished adjunct fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, dean emeritus of the Clemson College of Business and Behavioral Sciences, and a former executive director of the Federal Trade Commission.