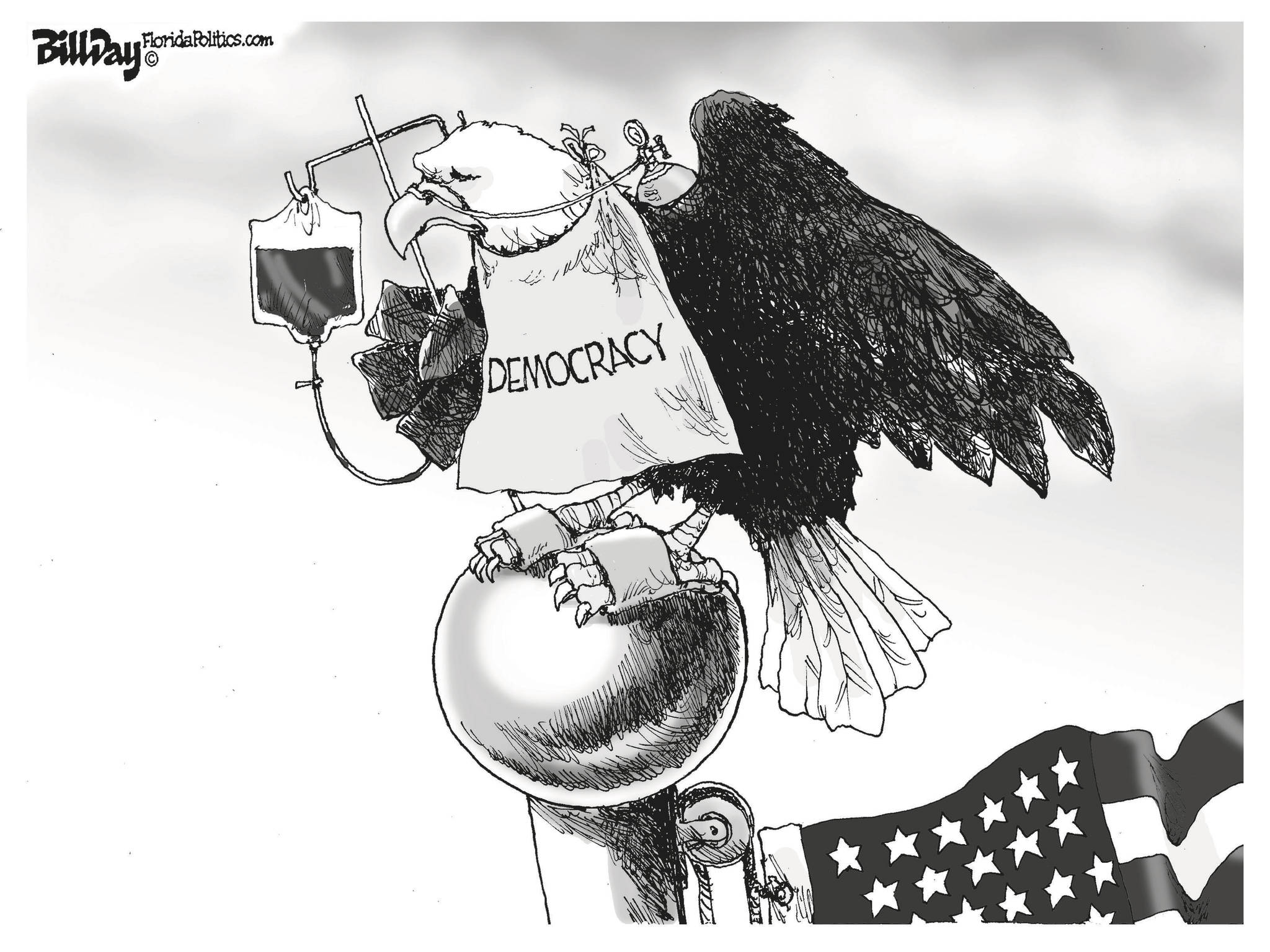

The majority of Americans today are anxious; they believe their democracy is under threat.

In fact, democracies deteriorate easily. As was feared since the times of Greek philosopher Plato, they may suddenly succumb to mob rule. The people will think they have an inalienable right to manifest their opinions — which means to state out loud whatever passes through their minds. They will act accordingly, often violently. They will make questionable decisions.

Democracies may pave the way to tyrants. Self-serving leaders will appear. They will seek to rewrite national history by purging it of complexity and inconvenient truths. They will capitalize on the widespread frustration and profit from the chaotic situation.

Should these leaders seize power, they will curtail the people’s participation in politics. They will discriminate based on race, sex or religion. They will create barriers to democratic participation by certain constituents, including moral tests or literacy tests.

So, one way democracies degenerate is because of cunning leaders. But democracies crumble also because of the people themselves. As an intellectual historian, I can assure you the specter of an ignorant populace holding sway has kept many philosophers, writers and politicians awake.

The American founders were at the forefront in the battle against popular ignorance. They even concocted a plan for a national public university.

Baron Montesquieu, a French philosopher who lived from 1689 to 1755, was a revolutionary figure. He had advocated the creation of governments for the people and with the people. But he had also averred that the uneducated would irremediably “act through passion.” Consequently, they “ought to be directed by those of higher rank, and restrained within bounds.”

The men known as America’s Founding Fathers, likewise, were very sensitive to this issue. For them, not all voters were created equal. George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton trusted the people — “the people” being, for them, white property-owning males, of course. But only if and when they had a sufficient level of literacy.

Thomas Jefferson was the most democratic-minded of the group. His vision of the new American nation entailed “a government by its citizens, in mass, acting directly and personally, according to rules established by the majority.”

He once gauged himself against George Washington: “The only point on which he and I ever differed in opinion,” Jefferson wrote, “was, that I had more confidence than he had in the natural integrity and discretion of the people.”

The paradox was that, for Jefferson himself, the “natural integrity” of the people needed to be cultivated: “Their minds must be improved to a certain degree.” So, while the people are potentially the “safe depositories” for a democratic nation, in reality they have to go through a training process.

Jefferson was adamant, almost obsessive: the young country should “illuminate, as far as practicable, the minds of the people at large.” More precisely, let’s “give them knowledge of those facts which history exhibits.”

“Educate and inform the whole mass of the people,” he kept repeating. It was an axiom in his mind “that our liberty can never be safe but in the hands of the people themselves, and that too of the people with a certain degree of instruction.”

Education had direct implications for democracy: “Wherever the people are well-informed,” wrote Jefferson, “they can be trusted with their own government.”

In 1787, Benjamin Rush, the Philadelphia doctor and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, published an “Address to the People of the United States.”

One of his main topics was the establishment of a “federal university” in which “every thing connected with government, such as history — the law of nature and nations — the civil law — the municipal laws of our country — and the principles of commerce — would be taught by competent professors.” Rush saw this plan as essential, should an experiment in democracy be attempted.

George Washington stressed the same idea. At the end of his second term as president, in December 1796, Washington delivered his eighth annual message to the Senate and the House of Representatives. He wished to awaken Congress to the “desirableness” of “a national university and also a military academy” whose wings would span over as many citizens as possible.

In his message, Washington embraced bold positions: “The more homogeneous our citizens can be made,” he claimed, “the greater will be our prospect of permanent union.”

A national university homogenizing the American people would likely be ill-received today anyway. We live in an age of race, gender and sexual awareness. Ours is an era of multiculturalism, the sacrosanct acknowledgment and celebration of difference.

But Washington’s idea that the goal of public education was to make citizens somewhat more “homogeneous” is worth reconsidering.

Were President Washington alive today, I believe he would provide his recipe for the people to remain the “safe depositories” of democracy. He would insist on giving them better training in history, as both Rush and Jefferson also advised. And he would especially press for teaching deeper, more encompassing political values.

He would say that schools and universities must teach the people that in their political values they should go beyond separate identities and what makes them different.

He would trust that, armed with such a common understanding, they would foster a “permanent union” and thus save democracy.

Maurizio Valsania, a professor of American history at the University of Turin, is writing a biography of George Washington.