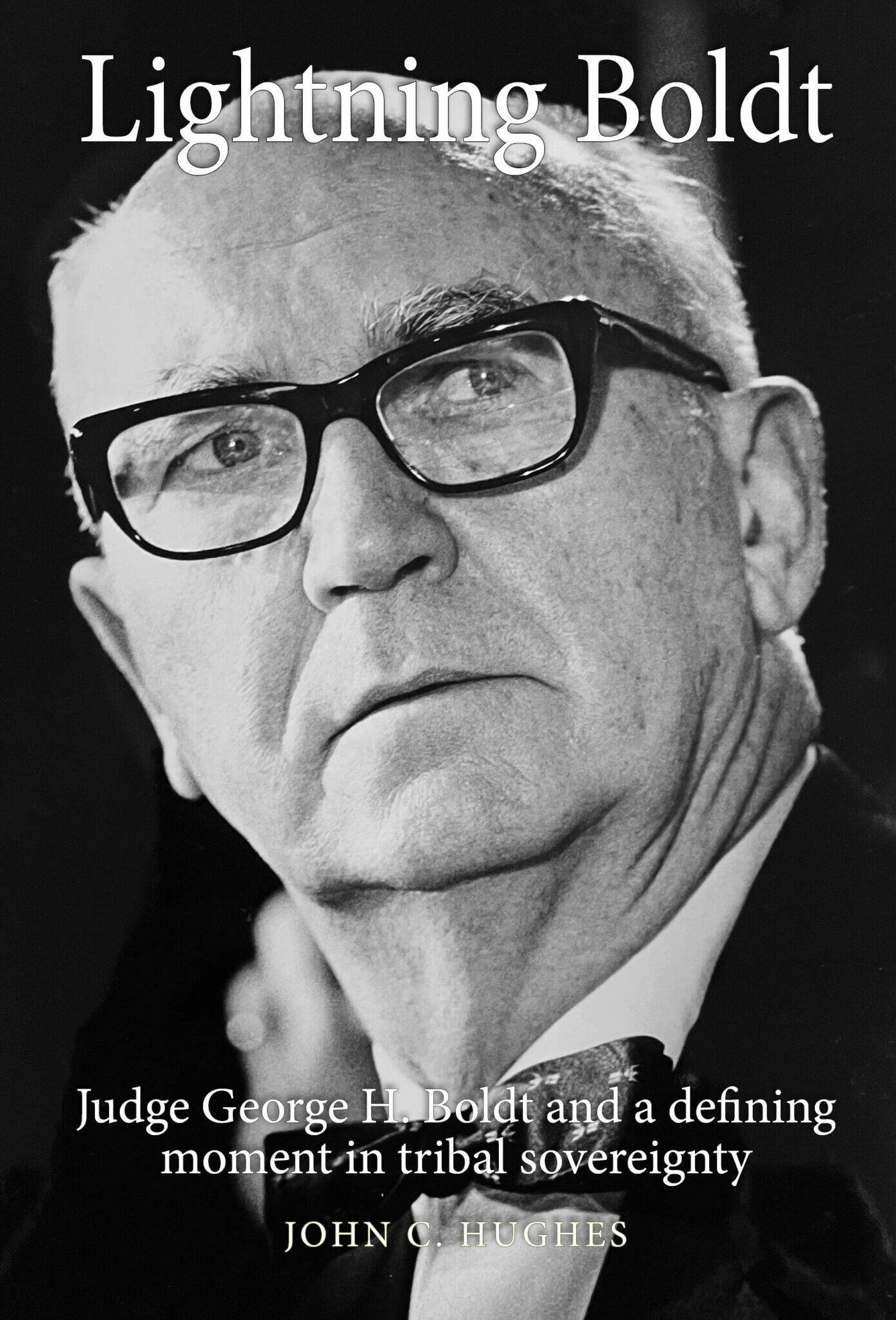

“Lightning Boldt,” is a biography of Judge George H. Boldt by John C. Hughes, Chief Historian for the Office of Secretary of State, and former editor and publisher of The Daily World. It’s a fascinating read for anyone interested in the history of fishing in Washington.

Hughes sat in Boldt’s courtroom and witnessed the trial that reaffirmed Native Americans’ right to up to 50 percent of the harvestable salmon and established them as co-managers of the fisheries with the state. The decision was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Judge Boldt was called “Lightning” for his reputation of speed and efficiency in throwing the book at mobsters, tax evaders and corrupt union leaders.

The son of Danish immigrants, Boldt was born in Chicago in 1903. He graduated from high school in Stevensville, Mont. The town was named after Isaac Stevens, a multi-tasker who became Washington’s first territorial governor, railroad surveyor and superintendent of Indian Affairs.

In the 1850s, Stevens negotiated 10 treaties where the Native Americans agreed to give up 100,000 square miles of their lands so Europeans could homestead it.

The treaties routinely guaranteed “The right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations, is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory.”

At the time, salmon runs were considered inexhaustible, so giving the Indians a right they already had was not a problem. During negotiations for the Treaty at the Chehalis River, Stevens sweetened the deal with 100 bushels of potatoes.

The treaties were translated from English into dozens of Indian languages through the Chinook Jargon, a 300-word pidgin mix of French, English and Indian words. The ethnologist James Swan called it, “a poor medium of conveying intelligence.”

It didn’t matter, since the treaties were largely ignored until more than 100 years later when George Boldt presided over the case of United States v. State of Washington.

It’s ironic that the Tribes did not want Boldt on the case because he was such an ardent fisherman. They assumed he was racist.

They probably didn’t know about Boldt’s WWII service in Burma as an OSS intelligence officer with a team of Nisei interpreters. These were Japanese Americans serving in the Armed Forces.

While 110,000 Japanese Americans were placed in internment camps during the war, the Nisei servicemen were described by Boldt as “Creditable American citizens given the toughest, dirtiest and most hazardous jobs in the war. Their record is equaled by few and excelled by none.”

Boldt’s detachment rescued 300 airmen who had crashed behind enemy lines.

After the war, Boldt stated America was a land where racism had no place. Boldt called himself a “4th of July Man,” alluding to his love of country, the law, his faith and his family.

He was called a “senile old Indian lover” by white fishermen who burned his effigy.

The violent reaction to his decision shocked Boldt who responded by saying the case should have been brought 50 years ago.

The Boldt Decision set off what was known as the Fish War, where each side of the dispute tried to kill the last fish. Fifty years later, many of our salmon runs are endangered or extinct. Fifty years from now, if we continue to ignore our responsibility to restore our fisheries, we’ll have only paper fish.

The Tribes regained their fishing rights, but with that comes the responsibility to do something the state can’t or won’t do: restore our fisheries. If the Tribes fail their responsibility, they’ll find half of nothing is nothing and the Boldt Decision might just as well have given them half of the buffalo.

The book is available for purchase via the Secretary of State’s online book store at https://www2.sos.wa.gov/store/#/detail/105/.

Pat Neal is a Hoh River fishing and rafting guide and “wilderness gossip columnist” whose column appears here every Thursday. He can be reached at 360-683-9867 or by email via patnealproductions@gmail.com.