Last month, Senate Democrats released a $3.5 billion budget package that they hope to pass alongside a $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill later this summer.

Advocates for educational equity applauded the specter of free community college and a long-overdue expansion of the Pell program that has, for decades, formed the cornerstone of college access for Black students. The inclusion of training dollars in the infrastructure legislation is key to making good on the bill’s economic — and equity — intent.

With good reason: Employment rates and wages increase among Black workers along with level of educational attainment. Black workers with some college or an associate’s degree are more likely to secure a good job than are those with no education beyond high school.

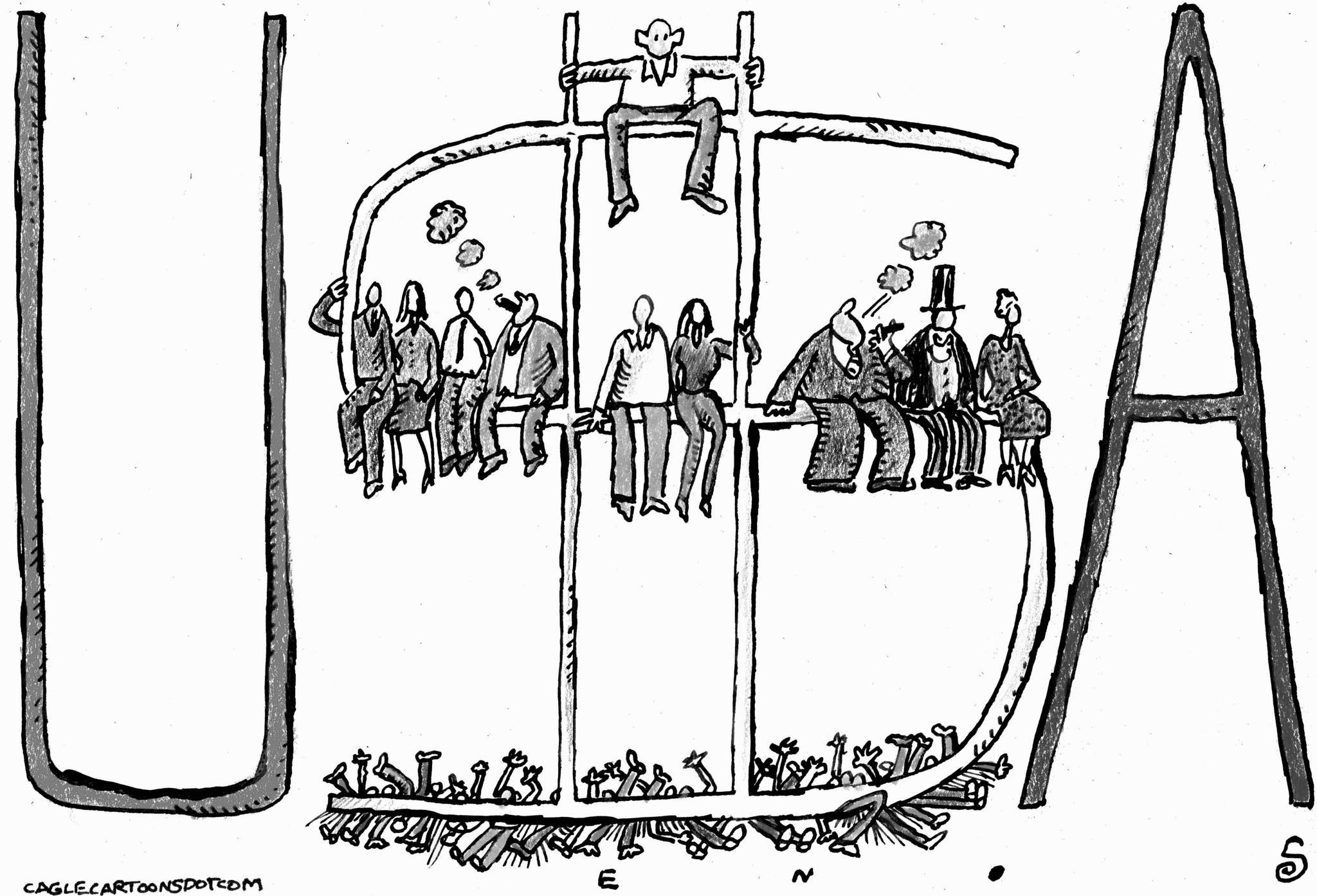

But even with education and training, Black workers earn less than white workers across nearly all education levels. In fact, white workers with a high school diploma earn more than Black workers with an associate’s degree. And despite recent increases in educational attainment for Black Americans, the Black unemployment rate has been twice as high as white unemployment for the past 50 years across nearly all levels of education.

Those data do not mean that postsecondary education is not still one of our nation’s most powerful levers for economic advancement. But they suggest that Black educational attainment, long characterized as the “great equalizer,” does not and cannot set Black Americans on equal economic footing.

So if we can’t educate and train our way to racial economic equity, what can we do to promote Black economic advancement and take aim at the racial wealth gap?

First, we must acknowledge that, for all their virtues, the U.S. postsecondary education and workforce training systems play a role in exacerbating occupational segregation.

Earnings vary greatly among college majors. While college access has increased among African Americans, they are overrepresented in majors that lead to low-paying jobs: Analysis from the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce found that African Americans represent 12% of the U.S. population, but they are “underrepresented in college majors associated with the fastest growing, highest-paying occupations,” such as information technology and computer science.

As a result, Black workers today are concentrated in low-wage jobs in industries that are susceptible to disruption by technology and automation.

Our educational institutions must do more to disrupt occupational segregation by not just increasing access, but also focusing on the success of Black learners and workers in education and training pathways associated with high wages — particularly those that provide entry into careers in the digital economy.

Second, we must recognize that disrupting occupational segregation is not the job of postsecondary education alone. Black workers with in-demand skills and credentials are still more likely to be unemployed, underemployed and less well compensated than their white peers with similar qualifications (even in similar occupations). For example, Black students earn computer degrees at twice the rate that they are hired by companies in the field.

A recent analysis in New York City found that Black bachelor’s degree holders earned on average nearly $22,000 less annually than their white peers. Research from McKinsey has found a $96 billion pay gap between Black and white workers within occupational categories, and evidence that Black workers have lower rates of professional advancement. Increasing access to careers in high-wage industries can be successful only if Black learners and workers do not face conscious or unconscious bias in hiring, compensation or on-the-job advancement opportunities.

Third, our colleges and universities must do more to leverage their financial resources and their incubation and acceleration capacity to support Black entrepreneurs, who start their businesses with less funding than white entrepreneurs and receive only 1% of venture capital funding.

According to an article published in the Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy, improving the rate at which Black entrepreneurs succeed should be a primary focus of efforts to leverage business ownership to reduce the racial wealth gap. The success of Black businesses and ventures will not only generate personal income — it will also contribute to the economic development and vitality of the communities in which Black Americans live and work.

Finally, we must look beyond the world of education, where visionary leaders and organizations are developing bold ideas to eliminate the Black-white wealth gap. Examples include innovations and strategies, such as baby bonds, free college, lifelong learning accounts, universal basic income and other transformative approaches. We must foster critical conversations among these visionaries. The education and workforce establishments are key to unlocking the potential of postsecondary education to address centuries of structural economic advantage for white Americans.

We can’t educate and train our way to racial economic equity. But there’s plenty we can — and must — do to move toward this goal. We can take bold, race-conscious approaches to transforming the learn-and-work ecosystem to promote Black economic advancement. And we can design bold, race-conscious solutions outside our postsecondary education and training systems to take aim at the racial wealth gap.

Michael Collins is a vice president at the nonprofit Jobs For the Future Inc.