By Dahleen Glanton

Chicago Tribune

Nearly two decades ago, George W. Bush asked the U.S. Supreme Court to intervene in a presidential election. Last week, Donald Trump implored the high court to do it again.

In the end, the court effectively awarded victory to Bush in 2000 over his Democratic opponent, then-Vice President Al Gore. The controversial decision ignited outrage and impaired public trust in the court, the only nonpartisan branch of our three-pronged democracy.

Former Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who cast the deciding vote, suggested a few years ago that the court made a mistake by getting involved. Justices should keep that in mind when deciding whether to take on Trump’s income taxes.

The current court, stacked heavily with conservative judges who recently have handed Trump a string of impressive victories including migrant asylums and his border wall, could be poised to make the same mistake again.

It requires only four justices to vote to hear a case. Doing so in Trump’s case would once again raise significant questions regarding the separation of power between the judicial, legislative and administrative branches of government.

For America’s sake, the court needs to take a pass this time.

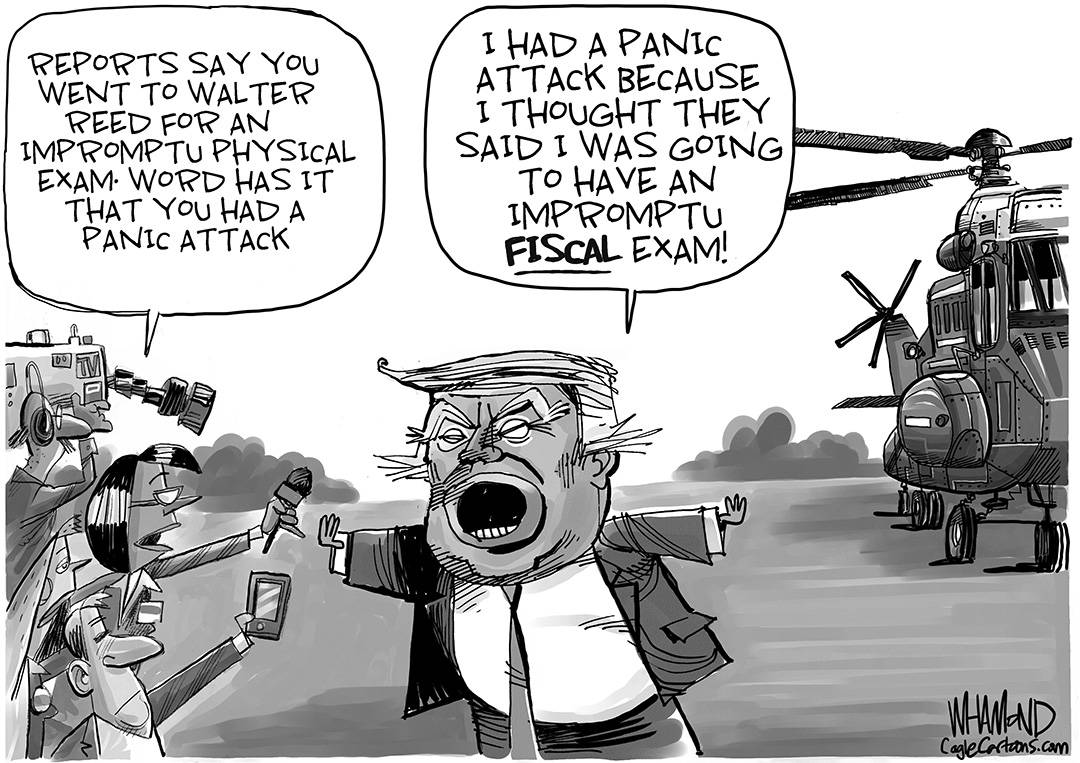

Last Thursday, Trump asked the high court to block a grand jury subpoena forcing his accountants to turn over eight years of tax records to Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr., whose office is conducting a criminal investigation of the president.

Late Friday, he took the case even further by asking the court to issue an emergency stay blocking the federal appeals court ruling that cleared the way for the House Oversight and Reform Committee to obtain his tax returns. If the court denies the stay, the returns must be released to the committee by Wednesday.

While the broader question regarding Congress’ subpoena powers would remain, Americans should be most concerned about the Vance petition, which could have a trickle-down effect on the presidential election that is less than 12 months away.

The Vance petition is much more than a dispute over the publication of Trump’s personal financial dealings, information he has sought to keep secret since launching his presidential campaign in 2015.

The filing lays out a complex argument that the president is immune to criminal prosecution while in office. It is easy to see why the Supreme Court might be tempted to enter such unprecedented territory and decide how far-reaching presidential powers should extend.

Such a ruling would determine whether a sitting president is above the law —a major point of contention between Democrats who are attempting to impeach Trump for apparent improper dealings with Ukraine and Republicans who insist that the proceedings are a political ploy to hamper Trump’s reelection.

Delving into this hypersensitive political argument would serve no useful purpose to the public, acting only to further divide the nation and tarnish the court’s reputation.

While Bush v. Gore had an immediate impact on the outcome of the 2000 election, putting an end to the vote recount that was taking place in Florida, the impact of Trump v. Vance likely would not come into play for months.

It would surely become an integral part of one candidate’s campaign strategy, and the court’s decision would loom large on Election Day.

Any decision by the high court, whether in Trump’s favor or against him, would allow one side to claim victory. If the court does what Trump is seeking, it would give weight to his claims of a Democratic “witch hunt” that has sought to invalidate his 2016 election and keep him from winning a second term.

If the court rules against Trump, Democrats could then argue that Trump, like every other American, is not above the law, giving credence to the impeachment effort and providing ammunition to Trump’s Democratic presidential challengers.

In an interview with the Chicago Tribune in 2013, O’Connor seemed to forebode that such a day would come again.

Looking back, she said, the court perhaps made a mistake by inserting itself in the 2000 election.

“It took the case and decided it at a time when it was still a big election issue,” said the Ronald Reagan appointee, who retired in 2006 and is now 89 years old. “Maybe the court should have said, ‘We’re not going to take it, goodbye.’”

O’Connor, a moderate judge who often cast the swing vote in major decisions, sided with conservatives in the 5-4 decision. She acknowledged that the case “stirred up the public” and “gave the court a less-than-perfect reputation.”

It was one of the most contentious elections America had seen in recent years. And according to O’Connor, “Probably the Supreme Court added to the problem at the end of the day.”

This was a remarkable revelation from a very wise woman. And it would behoove every justice, particularly the six who have joined the court since, to take her at her word.

Dahleen Glanton is a columnist for the Chicago Tribune.