By Rick Anderson

For the Grays Harbor News Group

When Edgar Martinez delivers his long-overdue Hall of Fame acceptance speech this July, he should include a shout-out for baseball’s sabermetricians.

Say what you will about analytics taking over baseball and other sports, there’s no way Seattle’s long-time designated hitter would have made it to Cooperstown without the support of its practitioners.

Martinez was one of four players elected to the Hall of Fame in balloting announced Tuesday.

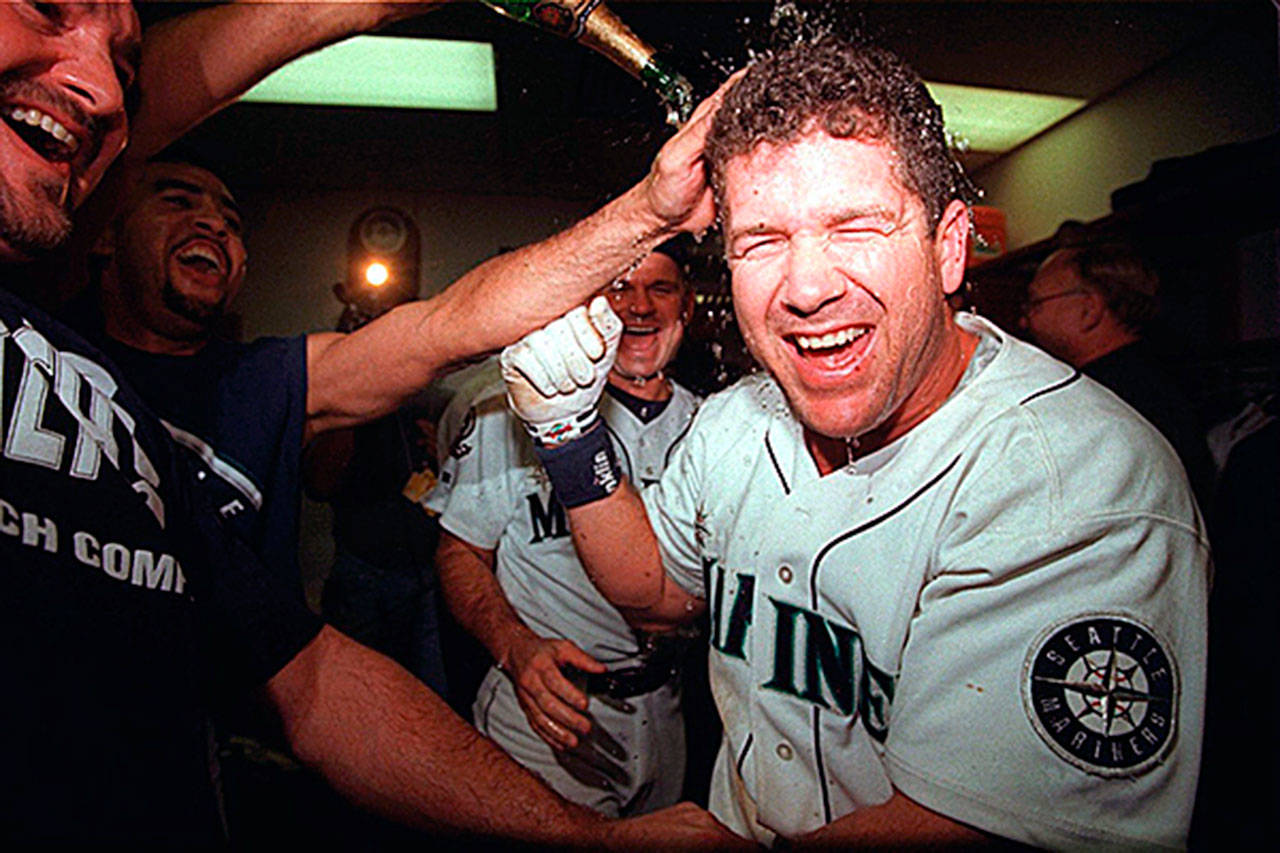

Despite a lifetime batting average of .312, two American League batting championships, a league RBI crown and seven All-Star selections (not to mention delivering the biggest hit in franchise history, the two-run double that won the 1995 American League Division series against the New York Yankees), Martinez seemed stuck in neutral for most of his 10 years on the Hall of Fame ballot. As recently as 2015, he was included on only 27 percent of ballots — 48 percent shy of the HOF standard.

That was due to the opposition of three significant factions. Contrary to the belief of many Northwesterners, big-city writers largely indifferent to the Mariners represent the least significant of those factions.

The others were old-school writers hung up on traditional statistics and those who would vote against any designated hitter.

The latter group was embodied by a Seattle writer (still active but no longer covering baseball) who asserted he would never vote for Martinez until he could prove he would have hit as effectively had he also been required to play defense.

With all due respect to the writer (who has done good work on non-baseball topics), this remains the dumbest Hall of Fame argument I’ve ever heard.

To begin with, how could you “prove” something like that? To the extent you could, Martinez did. His first batting title, in 1992, came when he was full-time third baseman.

In addition, the writer was applying a standard to a designated hitter that wasn’t required for other specialists. Since he became the first unanimous Hall of Fame selection Tuesday, New York Yankee reliever Mariano Rivera apparently didn’t have to prove to many voters that he could have pitched nine innings.

A more serious objection to Martinez’s candidacy was that his career statistics were light by Hall of Fame standards.

According to conventional wisdom, someone of Martinez’s ilk should approach 3,000 career hits. Because he lost the better part of two seasons to injury and a couple more seasons due to (stop me if you’ve heard this before) Mariners front-office stupidity, Edgar wound up with only 2,247.

Since Mariners management believed Jim Presley, a power hitter with greater knowledge of Outer Mongolia than awareness of the strike zone, was a better third baseman, Edgar didn’t get a crack at a full-time major-league job until he was 27.

Edgar’s Hall of Fame bandwagon didn’t gain momentum until noted sabermetricians began advocating his qualifications — and in some cases replacing old-liners as HOF voters.

Martinez was a sabermetricians’ dream — a high-average hitter who also hit home runs (more than 300 in his career) and drew walks.

In 1995, when he led the American League in batting average and runs batted in, he also paced the circuit in doubles and two statistics that are staples of analytics: runs scored and OPS (on-base plus slugging percentage). Martinez, in fact, led the league in OPS on three occasions.

Sabermetrics godfather Bill James once wrote that Martinez could have batted more than .400 in a hitter-friendly environment such as Denver’s Coors Field.

Jay Jaffe, one of the most influential of analytics-based younger writers, also made a strong argument for Edgar in his 2017 book, “The Cooperstown Casebook.”

Jaffe even argued that Martinez was an above-average defensive third baseman until switching to DH in the mid-1990s.

I’m not so sure I buy that observation. My memory of Edgar as a defensive player is admittedly fading, but I recall him as a reasonably sure-handed third baseman with very limited range and the bad habit of backing up to field hard-hit grounders.

Playing alongside Omar Vizquel, one of the greatest defensive shortstops of all time, undoubtedly bolstered Martinez’s defensive stats. At any rate, there are worse defensive players in the Hall of Fame.

But there aren’t many better hitters — and few, if any, designated hitters.

The powers-that-be in Major League Baseball, not noted for pro-Seattle bias, seem to have agreed. The annual award for the game’s top designated hitter is named in Martinez’s honor.

In excluding Martinez for that long, baseball writers demonstrated a serious disconnect from the athletes they covered. Nearly all of his ex-teammates and opposing pitchers that he faced regarded Edgar as a Hall of Famer.

That group includes Rivera, who once called Martinez the toughest hitter he ever faced (“He got my breakfast, lunch and dinner,” Rivera once said). The former Yankee great wasn’t being modest. Edgar batted .579 in career appearances against Rivera.

Presumably the greatest relief pitcher in baseball history didn’t need any additional evidence to prove that Edgar Martinez belonged in the Hall of Fame.