By Matt Calkins

The Seattle Times

On a blue-skied, 71-degree day in Seattle, you won’t find a soul at Safeco Field who isn’t stoked to be there.

You’ll see wide-eyed kids sitting on their fathers’ shoulders. You’ll see couples slow-sippin’ from Edgar’s Cantina. And, of course, you’ll see 50 guys in uniform carrying out their childhood dreams.

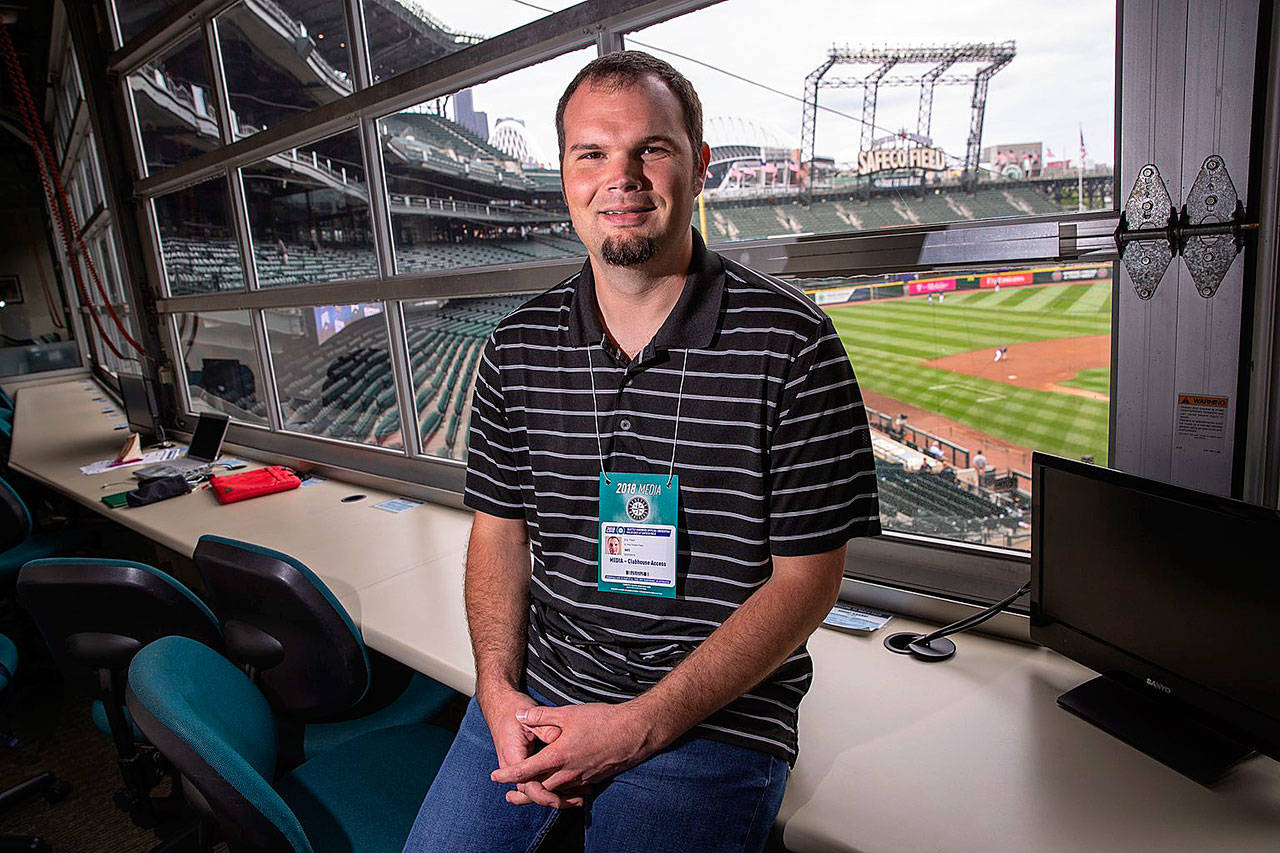

But I can assure you that Sunday, the most ecstatic man in the yard will be a 31-year-old sportswriter gazing on from the second row of the press box. His name is Eric Trent, a Western Washington student who will be typing his story with one hand and pinching himself with the other.

During his early to mid 20s, Trent couldn’t envision himself covering a junior-college water polo match, let alone a Mariners game. He was certain he’d either be dead or incarcerated instead.

These were justifiable thoughts for a man who spent five years as a homeless drug addict. For Eric, brushing shoulders with Felix Hernandez was about as plausible as flying to the moon.

“I never saw any of the good stuff coming,” Trent said.

Growing up in Bay Center on the Washington coast, Trent’s primary sports fantasy was to simply play catch with his father, Eric Trent Sr. But given how Trent Sr. has been in and out of prison his entire life — sometimes for drug possession, other times for burglary or possession of stolen firearms — that never happened.

In fact, when an 18-year-old Eric reunited with his old man after his latest prison release, Trent Sr. had a different idea for father-son bonding time. He took Eric to a house and smoked meth in front of him.

Trent had never been exposed to such a toxic drug before, although he had been abusing alcohol, weed and painkillers for three years. Incessantly angered or saddened by his absent father, he said the numbing effect of such substances hooked him immediately.

You wouldn’t know he was a budding addict just by looking at him, though. Trent’s loyalty and upbeat disposition prompted his fellow seniors at South Bend High to vote him “truest friend.”

Unfortunately, Trent wasn’t able to graduate with those who bestowed that title upon him. With booze and bud supplanting homework on his priority list, he fell short of the required number of credits and had to spend six more months in school.

This is when Trent’s mother, Jerri, a former EMT who now works with addicts, started to realize her son’s life was unraveling. She just couldn’t imagine the inevitable extent of it.

Trent’s first experience in journalism came when he was at South Bend covering the football team for his school paper. He felt sports and writing was an ideal fusion for his passions and vowed to pursue it as a career one day. But after graduating high school, he took a job as a commercial fisherman and slowly watched that goal drift away.

Trent was 21 when he first tried meth and was floored to see how the numbness lasted a full day. He added cocaine and heroin to his rotation and fully dedicated himself to chasing highs. Noticing her son was coming undone, Jerri begrudgingly kicked him out of her and Eric’s stepfather’s house, leaving him to couch surf for the better part of five years.

She never stopped caring, though. One night, Jerri knocked on the door of a heroin “crash house” and demanded to see Eric, who dragged himself to the entrance.

The next day, he called and told her how he’d heard she’d come by.

“You don’t remember seeing me?” Jerri said.

“No, Mom, I don’t.”

That’s when Jerri’s panic meter went all the way up to 11.

“I thought he was going to die,” she said. “I thought I was going to see him in an ambulance with a needle in his arm.”

It’s not that Trent desired this lifestyle — he just couldn’t fathom getting through a day sober. When he ran out of money, he’d offer to sell drugs for dealers, only to use the dope himself. He’d eventually lose the sum of his possessions when his truck caught fire and was destroyed.

One day, he approached his stepfather, Ray, showed him the needle holes in his arms and confessed he needed help. But before his treatment began, Trent stole firearms from his parents and sold them for drugs. So Ray called the police, who took him to jail, where he stayed because there was nobody he could call to bail him out.

“I had burned every bridge,” Trent said.

I’m not trying to pile on here, but rather detail the depths of Trent’s hell. It’s what he wants, too, because he knows there are others who can bounce back from a seemingly endless string of rock bottoms.

Trent’s first bottom came during a 30-day jail sentence, which he’d follow by entering a drug-treatment program. Didn’t matter. He relapsed upon release.

The next bottom came upon failing a urine test and being sent back to a 45-day treatment center. Didn’t matter. He relapsed upon release.

The truth is, despite the horrors surrounding him — despite the strain he was putting on his family, all Trent could think about was getting his next fix.

Then he met Stefanie Rotmark. Or for the purpose of this story, the angelic Stefanie Rotmark.

As a 26-year-old, Trent might not have had any money, friends, or family he could turn to, but like everyone that age, he did have a Facebook account. And one day, he decided to friend request Rotmark, who had gone to one of South Bend’s rival high schools.

Rotmark didn’t know anything about Trent’s past or addictions. She just liked that he would open the door for her and treat animals with kindness.

“I just felt like he had a heart of gold,” Rotmark said.

Few disputed that, even when Trent was sleeping on urine-and-feces-covered carpets with other users. It’s just that, when an addiction grabs hold of someone, it abducts their true selves.

Stefanie — the first “normie” Trent had dated since high school — began to notice inconsistencies in Eric’s behavior and asked for an explanation. Not wanting to lose her, he told her everything, then turned himself in to the police over an outstanding warrant.

The two had only been dating for four months, but Rotmark took an Incredible Hulk-like leap of faith and stood by him. Three months later, Trent was released from Pacific County Jail. He hasn’t used since — not even a sip of beer.

Still, those first couple years of sobriety might have been the hardest of Trent’s life. He would need to call a friend just to go to the grocery store because he had never done so sober.

But he eventually found a sense of purpose when he enrolled in Peninsula College in Port Angeles, where he took a full slate of classes and wrote for the student paper. And one day, his adviser, Rich Riski, told him he was good enough to write for a newspaper professionally.

Who knows if Riski thought his kind words would resonate so deeply, but Trent embraced the encouragement, slammed his foot on the throttle and hasn’t taken it off since.

He began freelancing for the Peninsula Daily News, covering high-school football and college women’s basketball. He’d eventually transfer to Western, where he went from reporter, to sports editor, to managing editor — and next semester, will become editor-in-chief of The Western Front.

He has also covered NCAA regional softball games at Washington for the Austin American-Statesman and Deseret News, run quotes at Mariners games for The Associated Press and, last month, covered the U.S. versus China women’s basketball game at KeyArena for the U.S. Olympic Committee.

“I sat at the press table about an hour before the game, and it said ‘Eric Trent, Team USA,’” Trent said. “That’s when I felt like I had made it. This was a dream come true.”

The dream-come-true sequels have been even better. The Pioneer Press of St. Paul, Minn., hired Trent to cover the entire Twins-Mariners series this weekend.

The Deseret News, meanwhile, paid him to cover the Sounders match against Real Salt Lake on Saturday.

I’m not saying you’re going to see Trent’s byline on A-1 of the WaPo in the next few months, but you don’t get these types of assignments without having a writing chop or two.

Personally, this is one of my favorite stories to have had the honor of reporting. Not just because of where Trent is now, but because of all the people who helped get him there. You had the tough-but-necessary love from Jerri and Ray, who kicked Eric out but embraced him upon his reform. You had the saintly Stefanie Rotmark, who defied all logic to support a man she knew could conquer his demons. You had encouraging advisers like Riski, and the yet-to-be mentioned freelance writer Jim Hoehn, who got Eric his first AP job.

And, of course, you have Trent — who endured all the tortures of climbing Everest before finally reaching the summit.

“Right now is the best time I’ve ever had. It seems like my life is finally coming together.

“I don’t even know how to say it,” Trent said. “I’m so far removed from my addiction that it’s really weird to think I was that other person at one time.”

Eric doesn’t try to contact his biological dad anymore, but last June, he did wish Ray Happy Father’s Day for the first time.

He also said he plans on finding a full-time writing gig when he graduates from Western next winter, but won’t go anywhere Stefanie doesn’t want to (smart man).

The biggest thing, I suppose, is that drugs don’t even enter his mind anymore. He hasn’t used for five years and hasn’t even been tempted for the past three.

Makes sense. Why would he?

From what I can tell, he wakes up high every morning.